• Of the Farm (1965)

• Couples (1968)

• Rabbit Redux (1971)

• A Month of Sundays (1975)

• Marry Me (1976)

• The Coup (1978)

• Rabbit Is Rich (1981)

• The Witches of Eastwick (1984)

• Roger’s Version (1986)

• S . (1988)

• Rabbit at Rest (1990)

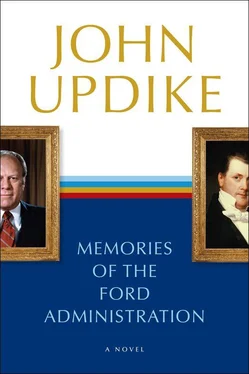

• Memories of the Ford Administration (1992)

• Brazil (1994)

• In the Beauty of the Lilies (1996)

• Toward the End of Time (1997)

• Gertrude and Claudius (2000)

• Seek My Face (2002)

• Villages (2004)

• Terrorist (2006)

• The Widows of Eastwick (2008)

SHORT STORIES

• The Same Door (1959)

• Pigeon Feathers (1962)

• Olinger Stories (a selection, 1964)

• The Music School (1966)

• Bech: A Book (1970)

• Museums and Women (1972)

• Problems (1979)

• Too Far to Go (a selection, 1979)

• Bech Is Back (1982)

• Trust Me (1987)

• The Afterlife (1994)

• Bech at Bay (1998)

• Licks of Love (2000)

• The Complete Henry Bech (2001)

• The Early Stories: 1953–1975 (2003)

• My Father’s Tears (2009)

• The Maples Stories (2009)

ESSAYS AND CRITICISM

• Assorted Prose (1965)

• Picked-Up Pieces (1975)

• Hugging the Shore (1983)

• Just Looking (1989)

• Odd Jobs (1991)

• Golf Dreams (1996)

• More Matter (1999)

• Still Looking (2005)

• Due Considerations (2007)

• Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu (2010)

• Higher Gossip (2011)

• Always Looking (2012)

PLAY MEMOIRS

• Buchanan Dying (1974)

• Self-Consciousness (1989)

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

• The Magic Flute (1962)

• The Ring (1964)

• A Child’s Calendar (1965)

• Bottom’s Dream (1969)

• A Helpful Alphabet of Friendly Objects (1996)

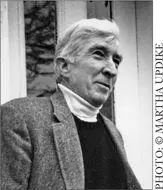

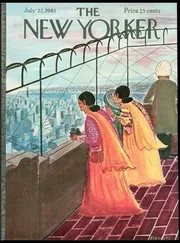

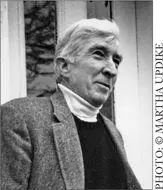

JOHN UPDIKE was born in Shillington, Pennsylvania, in 1932. He graduated from Harvard College in 1954 and spent a year in Oxford, England, at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. From 1955 to 1957 he was a member of the staff of The New Yorker . His novels have won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Rosenthal Foundation Award, and the William Dean Howells Medal. In 2007 he received the Gold Medal for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. John Updike died in January 2009.

As quoted in the preface to Of Grammatology , by Jacques Derrida, by the translator from the French, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who supplied the refinement in brackets and presumably the translation from the German, which coincides in this sentence (but not everywhere) with that of Jean T. Wilde and William Kluback.

Think: if we were members of a two-dimensional world, creatures pencilled onto a universal paper, how would we conceive of the third dimension? By strained metaphoric conjurations, like these of mine above. If we were dogs, how would we imagine mathematics? Yet there would be a few inklings — the hazy awareness, for instance, that the two paws we usually see are not all the paws we have, and that two and two might make something like four. It is important, for modern man especially, as we reach the limits of physics and astronomy, to be aware that there truly may be phenomena beyond the borders of his ability to make mental pictures — to conceive of the inconceivable as a valid enough category.

Installed in Philadelphia’s New Theatre in 1816, their first commercial use in America. Their very first use had occurred ten years earlier, when David Melville, of Newport, Rhode Island, bravely utilized gas to light his home and the street directly in front. Across the water, London first publicly installed gas in 1807, and Paris adopted it for street lighting in 1818.

Even as I write, dear fellow New Hampshire historians, a young lady of our state, exactly Ann Coleman’s last age of twenty-three, one Pamela Smart, a high-school media counsellor, has been indicted and convicted of seducing (with the aid of a videotape of 9½ Weeks , described in Halliwell’s Film Guide as a “Crash course in hot sex for those who wish to major in such studies”) a fifteen-year-old student with the successful aim of getting him and his thuggish pals to murder her husband. She remained impassive during her trial, but in a subsequent hearing, as her late husband’s aggrieved father prolongedly hectored her from the witness stand, she jumped up and in her thrilling young voice exclaimed, “Your Honor, I can’t handle this.” We all saw it on television; one had to love her for it. Her utterance brings me as close as I am apt to get to the truth of Ann Coleman’s conjectured and disputed suicide: Your Honor, she couldn’t handle it.

The obituary says “Anne,” but the tombstone has it “Ann.” I have chosen the name writ in stone.

Major John Henry Eaton, Jackson’s Secretary of War, whose marriage, at Jackson’s advice, to Margaret O’Neale Timberlake, a tavern-keeper’s daughter of considerable romantic experience even before her marriage at the age of sixteen to a navy purser whom the infatuated then-Senator Eaton used his influence to keep at sea while he comforted the lonely bride, failed to quiet scandalized Washington tongues, especially those wagging on the distaff side of the Calhoun camp: Buchanan had approached Eaton with the Adams-appointment question before approaching Jackson, and was rather curtly advised by the major to inquire of the general himself. And so he did.

George Kremer, Congressman from Pennsylvania and Ingham satellite, whose letter to the Columbian Observer of Philadelphia the January after Buchanan’s interview with Jackson claimed that Clay had offered to vote for whoever would give him the State Department; Clay’s challenge to a duel was retracted after it was rumored that Kremer proposed to duel with squirrel rifles. Jackson’s reference here assumes that Kremer’s basis was a conversation with Buchanan describing the epochal interview of December 30th.

Moore, ed., Works , Vol. II, pp. 378–82.

Moore, ed., Works , Vol. II, pp. 348–63.

Moore, ed., Works , Vol. II, pp. 368–9.

Does it need explaining? A matter of opportunity and romance, let’s say — the romance of the child’s fever, the closed door at the end of the hall, the look of the side yard from what had been our window, motionless in the blue night like a frozen garden of ferns. A sentimental carryover from the faculty party, where we had momentarily seemed again a couple. Don’t ask, Retrospect . At some point history becomes like topography: there is no why to it, only a here and a there .

Читать дальше