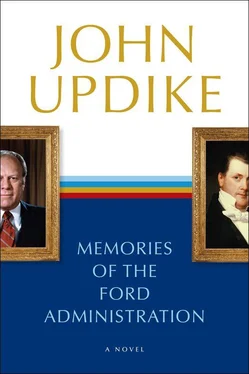

Memories of the Ford Administration

A Novel

by

John Updike

I am well aware that the reader does not require information, but I, on the other hand, feel impelled to give it to him.

— ROUSSEAU,

The Confessions

Man in his essence is the memory [or “memorial,” Gedächtnis ] of Being, but of Being. [1] As quoted in the preface to Of Grammatology , by Jacques Derrida, by the translator from the French, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who supplied the refinement in brackets and presumably the translation from the German, which coincides in this sentence (but not everywhere) with that of Jean T. Wilde and William Kluback.

— HEIDEGGER,

The Question of Being

Memories of the Ford Administration

From: Alfred L. Clayton, A.B. ’58, Ph.D. ’62

To: Northern New England Association of American Historians, Putney, Vermont

Re: Requested Memories and Impressions of the Presidential Administration of Gerald R. Ford (1974–77), for Written Symposium on Same to Be Published in NNEAAH’s Triquarterly Journal, Retrospect

IREMEMBER I was sitting among my abandoned children watching television when Nixon resigned. My wife was out on a date, and had asked me to babysit. We had been separated since June. This was, of course, August. Nixon, with his bulgy face and his menacing, slipped-cog manner, seemed about to cry. The children and I had never seen a President resign before; nobody in the history of the United States had ever seen that.

Our impressions — well, who can tell what the impressions of children are? Andrew was fifteen, Buzzy just thirteen, Daphne a plump and vulnerable eleven. For them, who had been historically conscious ten years at the most, this resignation was not so epochal, perhaps. The late Sixties and early Seventies had produced so much in the way of bizarre headlines and queer television that they were probably less struck than I was. Spiro Agnew had himself resigned not many months before; Gerald Ford was thus our only non-elected President, unless you count Joe Tumulty in the wake of Wilson’s stroke or James G. Blaine during the summer when poor Garfield was being slowly slain by the medical science of 1881, while Chester Arthur (thought to be corrupt, though he was an excellent fisherman and could recite yards of Robert Burns with a perfect Scots accent) hid in New York City from the exalted office he would finally accede to. If my children were like me, they were relieved to have a national scandal distract us from the scandal that sat like a clammy great frog, smelling of the swamp of irrecoverable loss, in the bosom of our family: my defection, my absence from the daily routine after dominating all the years of their brief lives with my presence, my coming and going, my rising and setting, my comforting and disciplining; my driving them to school and summer camp, to the beach and the mountains, to Maine and Massachusetts; my spelling of their mother in her dishevelled duties from breakfast to bedtime, from diaper-changing to, lately, sitting nervously in the passenger’s seat while Andrew enjoyed his newly acquired driver’s permit. I was the lonely only child of an elderly Republican couple, and fatherhood had been a marvel to me, an astonishing amusement; my teaching schedule at Wayward Junior College, then an all-female junior college beside the once-beautiful Wayward River here in southernmost New Hampshire, permitted an almost constant paternity, or it might be more accurate to say a fraternity — a coming-and-going facetious chumminess more like an elder brother’s than like a progenitor’s. Lacking siblings, I had, with my wife’s offhand compliance, created them. Born in 1936, in northern Vermont, where the mountains begin to flatten out and slouch toward Canada, I was named by my staunch parents after that year’s affable but unsuccessful candidate against Roosevelt, and became a father at the mere age of twenty-two, my first year in graduate school. The obstetrician, a stout woman wearing a lime-green skullcap, emerged from the depths of Cambridge City Hospital, wiped her hands like a butcher on his bloody apron, and shook mine with the stern words, “You have a son.” Buzzy followed when I was twenty-five and still not a Ph.D., and dear Daphne — the smallest at birth, a mere seven pounds ten, and the brightest-eyed ever after — two years later still, in 1963, the autumn Kennedy was shot and the second fall term of my first instructorship, at verdant and frosty Dartmouth. Salad days! Days of blameless leafing out! I had all the equipment of manhood except a grown man’s attitude. My queen, my palely freckled and red-headed bride, still had her waist then, her lissome milky legs, and an indolent willingness to try anything. Lyndon Johnson’s supercharged Sixties were about to break upon us like a psychedelic thunderstorm. We reined in our fertility, and hunkered down for happiness.

[ Retrospect editors: Don’t chop up my paragraphs into mechanical ten-line lengths. I am taking your symposium seriously, and some thoughts will run long as rivers in thaw, and others will snap off like icicles. Let me do the snapping, please.]

So I sat among my children less like a villain than like a fourth victim, another child of the gathering darkness (why did Nixon wait until the evening to quit? to avoid looking like a daytime soap opera?) and of the hurt and headless nation. This pose, of my being one more hapless inhabitant of our domestic desolation rather than the author of it, was in fact convenient for us all, freeing my children to like me still and to welcome my visits from my ascetic little bachelor pad across the river, in the quintessentially depressed industrial city of Adams — a one-mill hamlet renamed in 1797, honoring the harassed second President, a local boy of sorts — and to enjoy as best they could their visits to me and the meager entertainments Adams afforded: a bowling alley, a lakeside beach of imported sand, a Chinese restaurant where Daphne once got a fortune cookie without a fortune slip in it and burst into tears, thinking it meant she was about to die, and one surviving movie house in the depleted downtown, of the marqueed, velvety, rococo-lobbied type that in small cities everywhere was fast disappearing, passing to boarded-up, graffitiferous extinction through a lurid twilight as a triple-X triple-feature sex cinema. (Sex still had a good name during the Ford Administration. Betty Ford had been a footloose dancer for Martha Graham and announced at the outset of the administration that she and Gerald intended to keep sleeping in the same bed. Their children came and went in the headlines with lives that bore little more looking into than the lives of most young adults. In those years one-night stands, bathhouses, sex shops abounded. Venereal disease was an easily erased mistake. Syphilis, the clap — no problem. Crabs, the rather cute plague of Sixties crash pads, had moved on as urban rents went up, and herpes’ welts and blisters had yet to inflict their intimate sting. The paradise of the flesh was at hand. What had been unthinkable under Eisenhower and racy under Kennedy had become, under Ford, almost compulsory. Except that people were going crazy, as they had in ancient Rome, either from too much sex or from lead in the plumbing. Ford, a former hunk, got to women in a way Nixon hadn’t. Twice, I seem to remember, within a few weeks’ time, a female went after him with a gun; Squeaky Fromme was too spaced to pull the trigger, and Sara Jane Moore missed at close range. [

Читать дальше