Sayuri handed over her pencil to my undamaged hand and asked me to write a phrase into her book. I wrote, unsteadily, Where is she? (It is another example of my stellar luck that the fire spared my right hand, when I was born left-handed.) Sayuri paid no attention to the words I wrote; she was interested only in my dexterity. She moved the pen to my left hand, the one missing a finger and a half, and asked me to write another sentence. I managed to scribble out the words Fuck this. Sayuri looked at my literary undertaking, and commented that at least it was legible.

She wrapped things up by saying that I’d soon have an exercise program, and that was pretty exciting! “We’ll have you on your feet, strolling around, before you even know it!”

I said that I already goddamn well know how to walk, so how could I possibly get excited about that?

Sayuri pointed out-in a most gentle manner-that while I had known how to walk in my old body, I would have to learn how to do it in my new one. When I asked whether I’d ever be able to walk like a normal person again, she suggested that perhaps I was looking at the process in the wrong way and that I should just concentrate on the first steps rather than the entire journey.

“That’s just the kind of cheap Oriental wisdom I don’t need in my life.”

I suppose it was then that she realized I was looking for a fight and she took a step closer. She said that how well I would eventually walk depended on many things, but mostly on my willingness to work. “Your fate is in your own hands.”

I said I doubted it really mattered to her one way or the other how my progress went, as she’d get her paycheck just the same.

“That’s not fair,” Sayuri replied, providing just the opening that I was hoping for. I took the opportunity to explain to her what “not fair” really was. “Not fair” was the fact that when she went home in the evening to eat sushi and watch Godzilla on the late night show, I’d still be lying in my hospital bed with a tube sucking piss out of my body. That, I pointed out, was unfair.

Sayuri realized there was no point in continuing to talk to me, but still she was graceful. “You’re scared and I understand that. I know it’s difficult because you want to imagine the ending but you can’t even imagine the beginning. But everything will be okay. It just takes time.”

To which I replied: “Wipe that condescending look off your face, you Jap bitch.”

· · ·

Marianne Engel arrived at my bedside the next day with a small sheet of paper that she shoved into my hands. “Learn this,” she said, and drilled me on the words until I had committed them to memory.

An hour later, Sayuri Mizumoto came into the room, her head held high. She glanced at Marianne Engel, but then focused her eyes on mine. “The nurses said you wanted to see me.”

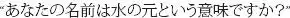

I did my best to affect a small bow in her direction, though it wasn’t easy lying down. I started to speak the words I’d memorized: “Mizumoto san, konoaidawa hidoi kotoba o tsukatte hontouni gomenasai. Yurushite kudasai.” (This roughly translates as I’m truly sorry that I spoke such terrible words to you the other day. Please forgive me. )

It was obvious that I’d caught her off guard. She replied. “I accept your apology. How did you learn the words?”

“This is my-friend, Marianne. She taught me.” Which was true, but it did not explain how Marianne Engel knew Japanese. I had asked, of course, but for the preceding hour she’d refused to discuss anything other than the mistakes in my pronunciation. I also did not know how, after seven days away from the hospital, she knew that I’d insulted Sayuri. Perhaps one of the nurses had told her, or Dr. Edwards.

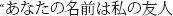

It was sheer coincidence that this was the first time the two women had met. Marianne Engel stepped towards Sayuri, bowed deeply, and said,

Sayuri’s eyes opened with astonished delight and she bowed back.

Marianne Engel nodded.

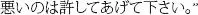

Sayuri smiled.

Marianne Engel shook her head in disagreement.

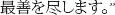

Marianne Engel bowed once more.

Sayuri stifled a giggle with a hand raised to her mouth.

Sayuri looked deeply pleased that my vile behavior the day before had produced such an unexpected meeting. She excused herself from the room with a wide smile, bowing one final time towards Marianne Engel.

Marianne Engel brought her mouth close to my ear, and whispered, “I don’t want to hear about you spitting black toads at Mizumoto san ever again. Talking with the mouth of a beast won’t ease your pain. You have to keep your heart open with love, and trust me. I promise that we’re moving towards freedom but I can’t do this alone.”

She moved away from my bed, pulled a chair from the corner, and sat heavily, with the tired look of a wife disappointed in her husband’s failure. Her strange little speech drove me to voice a question that I’d long wanted to ask but had been too afraid to: “What do you want from me?”

“Nothing,” she answered. “I want you to do absolutely nothing for me.”

“Why?” I asked. “What does that even mean?”

“Only by doing nothing will you truly be able to prove your love.”

“I don’t understand.”

“You will,” she said. “I promise.”

With this, Marianne Engel stopped talking about things that were going to happen in the future and decided to return to telling the story of her past. I did not believe any of it-how could I?-but at least it didn’t leave me, like our conversation, feeling dumb.

Growing up in Engelthal, I found my most difficult challenge was to keep my voice down. I understood that silence was an integral part of our spiritual welfare, but nevertheless I received many reprimands for my “excessive exuberance.” Really, I was simply acting as a child does.

It was not only sound that was muted at Engelthal, it was everything. All aspects of our lives were outlined by the Constitutions of the Order, a document so thorough that it had a full five chapters devoted just to clothing and washing. Even our buildings could have no elegance, for fear it might taint our souls. We had to sit in the dining hall in the same order that we took our places in the choir. During the meal, readings were given so we received spiritual nourishment as well as physical. We’d listen to passages from the Bible and a lot of St. Augustine, and sometimes The Life of St. Dominic, the Legenda Aurea, or Das St. Trudperter Hohelied. At least the readings distracted from the food, which was flavorless-spices were prohibited and we couldn’t eat meat without special permission, given only for health reasons.

Читать дальше