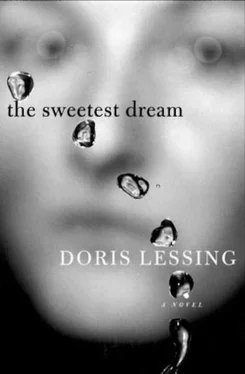

Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: perfectbound, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweetest Dream

- Автор:

- Издательство:perfectbound

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:0060937556

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweetest Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweetest Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweetest Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweetest Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Both were so sad, so distressed. Like people in a severe depression, the grey landscape that lay about them now seemed to be the only truth. 'It seems I am an old man, Julia,' he jested, trying to revive in him the courtly gent who kissed her hand and stood between her and all difficulties. That had been the convention. But he had been nothing of the sort, he now perceived, only a lonely old thing dependent on Julia for, well, everything. And she, the benevolent gracious lady, whose house had sheltered so many, though she had grumbled about it often enough, without him would have been an emotionally indigent old fool, besotted with a girl who was not even her granddaughter. So they seemed to each other and themselves, on their bad days, like shadows a bare branch lays on the earth, a thin and empty tracery, no warmth of flesh anywhere, and kisses and embraces are tentative, ghosts trying to meet.

Johnny heard that Wilhelm was living in Julia's house and came to say that he hoped there was no question of Wilhelm being left money. ' That has nothing to do with you, ' Julia said. ‘I shall not discuss it. And since you are here I shall tell you that I have had to support your abandoned wives and children and so I am not leaving you anything. Why don't you ask your precious communist party to give you a pension?'

The house had been left to Colin and to Andrew, and both Phyllida and Frances were provisioned with decent if not lavish pensions. Sylvia had said, ‘Oh, Julia, please don't, I don't need money.’But Julia left Sylvia's name in her will; Sylvia might not need it, but Julia needed to do it.

Sylvia was about to leave Britain, probably for a long time. She was going to Africa, to a mission station in the bush, in Zimlia. When Julia heard this she said, ' Then I shall not see you again.'

Sylvia went to say goodbye to her mother, having telephoned first. 'Kind of you to let me know,' said Phyllida.

The flat was a large mansion block in Highgate, and the entry-phone said that here were to be found Doctor Phyllida Lennox and Mary Constable, Physiotherapist. A little lift ground up through the lower floors like a biddable birdcage. Sylvia rang,

heard a shout, was admitted, not by her mother, but by a large and cheery lady on her way out. 'I'll leave you two to it,' said Mary Constable, revealing that there had been confidences. The little hall had an ecclesiastical aspect which, examined, turned out to be due to a large stained-glass panel, in boiled-sweet colours, showing Saint Frances with his birds – certainly modern. It was propped on a chair, like a signboard to spirituality. The door opened to show a large room whose main feature was a commodious chair draped with some kind of oriental rug, and a couch, inspired by Freud's in Maresfield Gardens, rigorous and uncomfortable. Phyl-lida was now a stout woman with greying hair in thick plaits on either side of a matronly face. She wore a kaftan of many colours, and multiple beads, earrings, bracelets. Sylvia, who had been carrying in her mind a limp, weepy, flabby female, had to adjust to this hearty woman, who clearly had acquired confidence.

' Sit down,’ said Phyllida, indicating a chair not in the therapeutic part of the room. Sylvia sat carefully on its very edge. A spicy provocative smell... had Phyllida taken to wearing perfume? No, it was incense, emanating from the next room, whose door was open. Sylvia sneezed. Phyllida shut the door, and sat herself in her confessor's chair.

‘And so, Tilly, I hear you are going to convert the heathen?'

‘I am going to a hospital, as a doctor. It is a mission hospital. I shall be the only doctor in the area. '

The big strong woman, and the wisp of a girl – so she still seemed – were being made conscious of their differences. Phyllida said, ‘What a pasty-face! You' re like your father, a proper weed he was. I used to call him Comrade Lily. His middle name was Lillie, after some old Cromwell revolutionary. Well, I had to keep my end up somehow, when he came the commissar at me. He was worse even than Johnny, if you can believe that. Nag, nag, nag. That bloody Revolution of theirs, it was just an excuse to nag at people. Your father used to make me learn revolutionary texts by heart. I am sure I could recite the Communist Manifesto for you even now. But with you it's back to the Bible. '

'Why back to?'

'My father was a clergyman. In Bethnal Green.'

'So what were they like, my grandparents?'

‘I don't know. Hardly saw them after they sent me away. I didn't want to see them. I went to live with my aunt. Obviously they didn't want to see me, sending me away like that for five years, so why should I want to see them?'

‘Do you have any photographs of them?'

‘I tore them up. '

‘I would have liked to see them. '

‘Why should you care? Now you are going away. Just as far away as you can get, I suppose. A little thing like you. They must be mad, sending you. '

' However that may be. But I've come to say something important. And what is this Doctor on your nameplate?'

'I am a Doctor of Philosophy, aren't I? I took Philosophy at university. '

‘But we don't use Doctor like that in his country. Only the Germans do. '

‘No one can say I am not a doctor. '

‘You'll get into trouble. '

‘No one has complained yet. '

' That is what I've come to see you about... mother, this therapy you' re doing. I know you don't need any kind of training for it but...’

‘I’m learning on the job. Believe me, it's an education. '

‘I know. People have said you have helped them. '

Phyllida seemed to turn into someone else: she flushed, she sat forward clasping her hands, was smiling and confused with pleasure. ' They did? You've heard good things?'

‘Yes, I have. But what I want to suggest is, why not actually take a course? There are some good ones. '

‘I’m doing all right as I am. '

' Tea and sympathy are all very well...’

‘I can tell you, there have been times I could have done with tea and sympathy...' and her voice was sliding into the knell of her complaint. Sylvia's muscles were already propelling her upwards, when Phyllida said, 'No, no, sit down, Tilly.'

Sylvia sat, and pulled from a briefcase a stack of paper, which she handed to her mother. ' I've made a list of the good ones. One of these days someone is going to say they have a headache or a stomachache and you'll say it's psychosomatic, but it's cancer or a tumour. Then you'll blame yourself. '

Phyllida sat silent, holding the papers. In came Mary Constable, all confidential smiles.

' Come and meet Tilly,’ said Phyllida.

‘How are you, Tilly?’ said Mary, actually embracing the reluctant Sylvia.

‘Are you a psychotherapist too?'

‘I’m physio,’ said Phyllida's companion... lover? Who knew, these days? 'I train physio students. We say that between us we deal with the whole person,’ said cheerful Mary, radiating a persuasive intimacy and faint aromas of incense.

‘I must go,’ said Sylvia.

‘But you've just come,’ said Phyllida, with satisfaction that Sylvia was behaving as she had expected she would. ' I've got a meeting,’ said Sylvia. ' Said just like Comrade Johnny. ' ‘I hope not,’ said Sylvia.

'Then, goodbye. Send me a postcard from your tropical paradise.' 'They have just finished a rather nasty war,' said Sylvia.

Sylvia rang Andrew in New York, was told he was in Paris, then from there, that he was in Kenya. From Nairobi she heard his voice, crackly and faint.

' Andrew, it's me. '

' It's who? Damn this line. Well, we won't get a better. Third World tech, ' he shouted.

'It's Sylvia.'

Even through the crackles she heard his voice change. 'Oh, darling Sylvia, where are you?'

‘I was thinking of you, Andrew. '

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweetest Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.