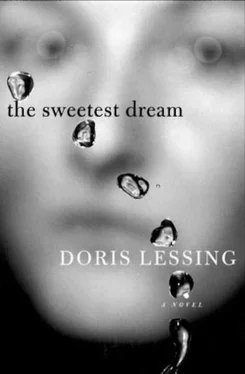

Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: perfectbound, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweetest Dream

- Автор:

- Издательство:perfectbound

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:0060937556

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweetest Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweetest Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweetest Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweetest Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'Not to an ordinary mind,' said Rupert.

Sylvia said, ' It amounts to this, Johnny. No government in this country could even suggest protecting the people, even to the minor extent of fall-out shelters, because of you and your lot. The Campaign for Unilateral Nuclear Disarmament – it has such power that the government is afraid of it.'

' That's righ' ,’ said James. ' That's how i' ough' a be. '

‘Why do you talk in that ugly way?’ said Julia. ' That isn't how you need to speak. '

' If you don't talk ugly then you' re posh,’ said Colin, talking posh. ‘And you don't get work in this free country. Another tyranny. '

Johnny and James showed signs of leaving.

'I'm going back to the hospital,' said Sylvia. 'At least I can have an intelligent conversation there.'

‘I want to see the letter you are talking about,’ said Johnny.

'Why?' asked Sylvia. 'You aren't even prepared to discuss what it says. '

' Obviously,’ said Andrew, ' he wants to inform the Soviet Embassy here of its contents. So that it can be traced, and the writers can be sent to labour camps or shot. '

' Labour camps do not exist,’ said Johnny. ‘And if they did once – to a certain extent – they have been exaggerated – then they don't exist now. '

‘Oh, Lord,’ said Andrew. ‘You really are a bore, Johnny. '

' A bore isn't dangerous,’ said Julia. ' Johnny and his kind are dangerous.'

' That is very true,’ said Wilhelm, politely, as ever, to Johnny. ‘You are very dangerous people. Do you realise, if there is a nuclear accident here, in this country, or if a bomb is dropped by some madman, let alone if there is a war, then millions of people could die because of you?'

‘Well, thanks for the snack,’ said Johnny.

' Thanks for nothing,’ said Sylvia, almost in tears. ‘I should have known there was no point even in trying. '

The two men left. Andrew and Sophie left, their arms around each other. Colin's sardonic smile at the sight did not go unnoticed by them or by anybody.

Sylvia said, 'Anyway, there's a committee. So far it's all doctors, but we are going to expand.'

'Enrol us all,' said Colin, 'but expect to find glass in your wine and frogs through the letterbox. '

Sylvia embraced Julia, and left.

' Don't you think it is strange that stupid people should have such power?’ said Julia, almost weeping, because ofSylvia's careless farewell.

‘No,’ said Colin.

‘No,’ said Frances.

'No,' said Wilhelm Stein.

'No,' said Rupert.

'But this is England, this is England...'said Julia.

Wilhelm put his arm around her, and led her out and up the stairs.

There were left Frances and Rupert, Colin and the dog. A little situation: Rupert wanted to stay the night, and Frances wanted him to, but she was afraid – she could not help it – of Colin's reaction.

‘Well, you two,’ said Colin, and it was an effort for him, ' bedtime, I think. ' Giving them permission. He began teasing the dog until it barked.

' There you are, ' he said. ' He always has the last word. '

A couple of weeks later Frances with Rupert, Julia and Wilhelm, Colin, were at a meeting called by the young doctors. There were about two hundred there. Sylvia opened the meeting, speaking well. Other doctors, and then more people followed. Members of the opposition had got wind of the meeting, and there were a group of thirty, who kept up a steady shouting, whistling, and shouts of Fascists! War mongers! CIA! Some were from the staff of The Defender. As our group left, some youths waiting at the exit caught hold of Wilhelm Stein and threw him against railings. Colin at once laid into them and put them to flight. Wilhelm was shaken, it was thought no more than that, but he had cracked ribs and he was taken to Julia's house and put to bed there.

‘And so, my dear, ' he said, in a voice that was wheezy, and old. ‘And so, Julia, I have achieved the impossible: I am living with you at last.' This was the first the others had heard Wilhelm wanted to move in.

He was put into the room that had been Andrew's and Julia proved a devoted if fussy nurse. Wilhelm hated it, having seen himself always as Julia's cavalier, her beau. And Colin too, that abrasive young man, surprised the others, and perhaps himself, by a charming attentiveness to the old man. He sat with him, and told him stories about 'my dangerous life on the Heath, and in the Hampstead pubs', in which Vicious figured as something not far off the Hound of the Baskervilles. Wilhelm laughed, and begged Colin to desist, because his ribs hurt. Doctor Lehman came, and told Frances and Julia and Colin that the old man was on his way out. ' These falls are not good at his age. ' He prescribed sedatives for Wilhelm and a variety of pills for Julia whom he was at last permitting to think of herself as old.

Frances and Rupert at The Defender demanded their right to put an opposing view to that of the unilateral disarmament people, and wrote an article, which earned dozens of letters nearly all furiously opposing, or abusive. The Defender offices seethed and Frances and Rupert found curt or angry notes on their desks, some anonymous. They realised this rage was too deep in some part of the collective unconscious to be reasoned with. It was not about protecting or not protecting the population: they had no idea what it was really about. It was very unpleasant at The Defender. They decided to leave, well before it suited either of them financially. They were simply in the wrong place. Always had been, Frances decided. And all those long well-reasoned articles on social issues? Anyone could have written them, Frances said. Rupert almost at once got another job on a newspaper described as fascist by a typical Defender addict, but as Tory, by the populace. ‘I suppose I must be a Tory,' said Rupert, 'if we are going to take these old labels seriously. '

The week they resigned a parcel of faeces was pushed through the door of Julia's house, but not the front door, the one into Phyllida's flat from the outside steps to the basement. A death-threat arrived, anonymous, to Frances. And Rupert too was sent a death-threat, together with some photographs ofHiroshima after the bomb. Phyllida came up – the first time for months – to say she objected to being drawn into this ' ridiculous debate' . She was not prepared to deal with shit, not on any level. She was leaving.

She was going to share a flat with another woman. And then she was gone.

As for the poisonous debates over protecting or not protecting the population, soon it would be generally agreed that war had been prevented for so long because the possibly belligerent nations had nuclear weapons and did not use them. There remained, however, questions that this admission did not answer. Accidents at nuclear installations might happen and often did, and were usually hushed up. In the Soviet Union there had been accidents that had poisoned whole districts. There were madmen in the world who would not hesitate to drop 'the bomb', or several, but it was at least strange that this threat was usually referred to in the singular. The population remained unprotected, but the violence, the poison, the rage of the debates, simply fizzled out – stopped. If there ever had been a threat, it existed now. But the hysteria evaporated. ' A strange thing,’ said Julia, in her new, sorrowful, slow voice.

Wilhelm was still at Julia's, and his big luxurious flat was empty. He kept saying that he was going to bring all his books over, and put an end to this ' amazingly absurd situation' , with him neither living with Julia, nor not. He kept making dates with the movers, and cancelling them. He was not himself. He had to be humoured. Julia was as distressed. The two of them together were now like sick people who wanted to be responsible for each other, but their own weakness forbade it. Julia had succumbed to pneumonia, and for a while the two invalids were on different floors, sending notes to each other. Then Wilhelm insisted on getting up to visit her. She saw this old man shuffling into her room, holding on to the edges of doors, and chair tops, and thought he looked like an old tortoise. He was in a dark jacket, wore a small dark cap, for his head was always cold, and he poked his head forward. And she – he was shocked by her, the bones of her face prominent, her arms like sticks of bone.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweetest Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.