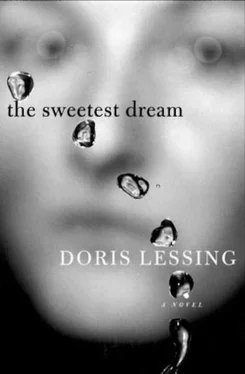

Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: perfectbound, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweetest Dream

- Автор:

- Издательство:perfectbound

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:0060937556

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweetest Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweetest Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweetest Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweetest Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Some people have come to think that our – the human being's – greatest need is to have something or somebody to hate. For decades the upper classes, the middle class, had fulfilled this useful function, earning (in communist countries) death, torture and imprisonment, and in more equable countries like Britain, merely obloquy, or irritating obligations, like having to acquire a cockney accent. But now this creed showed signs of wearing thin. The new enemy, men, was even more useful, since it encompassed half the human race. From one end of the world to the other, women were sitting in judgement on men, and when Frances was with The Defender women, she felt herselfto be part ofan all-female jury that has just passed a unanimous verdict of Guilty. They sat about, in leisure moments, solidly in the right, telling little anecdotes of this man's crassness or that man's delinquency, they exchanged glances of satirical comment, they compressed their lips and arched their brows, and when men were present, they watched for evidence of incorrect thought and then they pounced like cats on sparrows. Never have there been smugger, more self-righteous, unself-critical people. But they were after all only a stage in this wave of the women's movement. The beginning of the new feminism in the Sixties resembled nothing so much as a little girl at a party, mad with excitement, her cheeks scarlet, her eyes glazed, dancing about shrieking, 'I haven't got any knickers on, can you see my bum?' Three years old, and the adults pretend not to see: she will grow out of it. And she did. 'What me? I never did things like that... oh, well, I was just a baby. '

Soberness soon set in, and if the price to be paid for solid worth was an irritating self-righteousness, then surely it was a small price for such serious, scrupulous research, the infinitely tedious rooting about in facts, figures, government reports, history, the work that changes laws and opinions and establishes justice.

And this stage, in the nature of things, would be succeeded by another.

Meanwhile Frances had to conclude that working for The Defender was not unlike being Johnny's wife: she had to shut up and think her own thoughts. This was why she had always taken so much work home. Keeping one's counsel, after all, takes it out of you, wears you down, it had taken her much longer to see that many of the journalists working for The Defender were the offspring of the comrades, though one had to know them a while before the fact emerged. If one had a Red upbringing, then one shut up about it – too complicated to explain. But when others were in the same boat? But it was not only The Defender. Amazing how often one heard, 'My parents were in the Party, you know.' A generation of Believers, now discredited, had given birth to children who disowned their parents' beliefs, but admired their dedication, at first secretly, then openly. What faith! What passion! What idealism! But how could they have swallowed all those lies? As for them, the offspring, they owned free and roving minds, uncontaminated by propaganda.

But the fact was, the atmosphere of The Defender and other liberal organs had been 'set' by the Party. The most immediately visible likeness was the hostility to people not in agreement. The left-wing or liberal children of parents they might describe as fanatics maintained intact inherited habits of mind. ' If you are not with us, you are against us. ' The habit of polarisation, ' If you don't think like us, then you are a fascist. '

And, like the Party in the old days, there was a plinth of admired figures, heroes and heroines, usually not communists these days, but Comrade Johnny was a prominent figure, a grand old man, one of the Old Guard, to be pictured as standing eternally on a platform shaking his clenched fist at a reactionary sky. The Soviet Union still held hearts, if not minds. Oh, yes, ' mistakes' had been made, and ' mistakes' had been admitted to, but that great power was defended, for the habit of it had gone too deep.

There were people in the newspaper that were whispered about: they must be CIA spies. That the CIA had spies everywhere could not be in doubt, so they must be here too: no one ever said that the KGB had its Soviet fingers in this pie, manipulating and influencing, though that was the truth, not to be admitted for twenty years. The USA was the main enemy: this was the unspoken and often loudly asserted assumption. It was a fascist militaristic state, and its lack of freedom and true democracy was attacked continually in articles and speeches by people who went there for holidays, sent their children to American universities, and took trips across 'the pond' to take part in demos, riots, marches and meetings.

A certain naive youth, joining The Defender because of his admiration for its great and honourable history of free and fair thought, rashly argued that it was a mistake to call Stephen Spender a fascist for campaigning against the Soviet Union and trying to make people accept 'the truth' – which phrase meant the opposite of what the communists meant by it. This young man argued that since everyone knew about the rigged elections, the show trials, the slave camps, the use of prison labour, and that Stalin was demonstrably worse than Hitler, then surely it was right to say so. There was shouting, screaming, tears, a scene that almost came to blows. The youth left and was described as a C I A plant.

Frances was not the only one who longed to leave this prickly dishonest place. Rupert Boland, her good friend, was another. Their secret dislike of the institution they worked for was what first united them, and then when both could have left to get work on other newspapers, they stayed – because of the other. Which neither knew, for it was not confessed for a long time. Frances had found she was in danger of loving this man, but then when it was too late, she did. And why not? Things progressed in an unhurried but satisfying way. Rupert wanted to live with Frances. 'Why not move in with me?' he said. He had a flat in Marylebone.

Frances said that once in her life she wanted her own home. She would have enough money in a year or so. He said, 'But I'll lend you the money to make the difference.' She baulked and made excuses. It would not be entirely her place, the spot on the earth where she could say, This is mine. He did not understand and was hurt. Despite these disagreements their love prospered. She went to his flat for nights, not too often, because she was afraid of upsetting Julia, afraid of Colin. Rupert said, 'But why? You're over twenty-one?'

When you are getting on there occur often enough those moments when whole tangles of bruised and bleeding history simply wrap themselves up and take themselves off. She did not feel she could explain it to him. And she didn't want to: let it all rest. Basta. Finis. Rupert was not going to understand. He had been married and there were two children, who were with their mother. He saw them regularly, and now so did Frances. But he had not been through the savage impositions of adolescence. He said, just like Wilhelm, ‘But we aren't teenagers, hiding from the grown-ups.' 'I don't know about that. But in the meantime – it's fun. '

There was something that could have been a problem, but wasn't. He was ten years younger than she was. She was nearly sixty, he ten years younger! After a certain age ten years here or there don't make much difference. Quite apart from sex, which she was remembering as a pleasant thing, he was the best of company. He made her laugh, something she knew she needed. How easy it was to be happy, they were both finding, and with an incredulity they confessed. How could it be that things were so easy that had been difficult, wearisome, painful?

Meanwhile, there seemed to be no accommodation for this love, which was of the quotidian, daily-bread sort, not at all a teenagers' romp.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweetest Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.