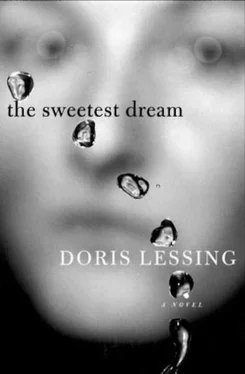

Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Doris Lessing - The Sweetest Dream» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: perfectbound, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sweetest Dream

- Автор:

- Издательство:perfectbound

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:0060937556

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sweetest Dream: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sweetest Dream»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sweetest Dream — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sweetest Dream», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The absurdity of this showed itself at once. Colin went white, and sat silent. ' Colin, for God's sake, you know perfectly well...’

The dog intervened. ' Yap, yap, ' it went, ' yap, yap. '

Frances collapsed laughing. Colin smiled, bitterly.

The fact was, the weight of his main accusation lay there between them, a poisoned thing.

'Where did you get all that confidence? Father saving the world, a few million dead here, a few million dead there and you, Do come in and make yourself at home, I'll just kiss the sore places and make them better. ' He sounded beaten into the earth by years of his miserable childhood, and he actually looked like a little boy, eyes full, lips trembling. And Vicious, leaving his chair, came to his master, leaped up on to his knee and began licking his face. Colin put his face – as much of it as would go -into the tiny dog's back, to hide it. Then he lifted it to say, ' Just where did you get it all from, you lot? Who the bloody hell are you – world-savers every one, and making deserts... Do you realise? We' re all screwed up. Did you know Sophie dreams of gas chambers and none of her family was anywhere near them?’And he got up, cuddling the dog.

‘Wait a minute, Colin...’

‘We've dealt with the main item on the agenda – Sophie. She is unhappy. She will go on being unhappy. She will make Andrew unhappy. Then she will find someone else and go on being unhappy. '

He ran out of the room and up the stairs, the little dog barking in his arms, its high absurd yap, yap, yap.

Something was going on in Julia's house that none of the family knew about. Wilhelm and Julia wanted to get married, or at least, for Wilhelm to move in. He complained, humorously at first, that he was being forced to live like a teenager, with little assignations to meet his love at the Cosmo, or for visits to restaurants; he might spend all day and half the night with Julia, but then had to go home. Julia fended off the situation, with jokes to the effect that at least they were not yearning like teenagers for a bed. To which he replied that there was more to a bed than sex. He seemed to remember cuddles, and conversations in the dark, about the ways of the world. Julia did wonder about sharing a bed after so many years as a widow, but increasingly saw his point. She always felt bad, staying comfortably in her room, when he had to go home, through whatever weather there was. His home was a very large flat, where once his wife, who was dead long ago, and two children, now in America, had lived. He was hardly ever in this flat. He was not a poor man, but it was not sensible, keeping up his flat with its doorman and the little garden, while there was this big house of Julia's. They discussed, then argued, then bickered about how things could be arranged.

For Wilhelm to live with Julia in the four little rooms that were enough for her – out of the question. And what would he do with his books? He had thousands of them, some of them part of his stock as a book dealer. Colin had taken over the floor beneath Julia, had colonised Andrew's room. He could not be asked to move – why should he? Of all the people in this house, except Julia herself, he needed most his place, his little secure place in the world. Below Colin was Frances in two good rooms and a little one. And on that floor was the room that was Sylvia's, even if she only came back to it once a month. It was her home and must remain so.

But why should Frances not be asked to move? – Wilhelm wanted to know. She earned enough money these days, didn't she? But Julia refused. She saw Frances as a woman used by the Lennox family to do the job of bringing up two sons, and now – out. Julia had never forgotten how Johnny had demanded that she should go away, into some little flat or other, when Philip died.

Beneath Frances was the big sitting-room that stretched from front to back of the house. It might take more shelves for Wilhelm 's books? But Wilhelm knew Julia did not want this room to be sacrificed. There remained Phyllida. She could now well afford to find her own place. She had the money Sylvia had assured her and she earned steady money as a psychic and fortune teller, and – increasingly – a therapist. When the family heard that Phyllida was now a therapist, the jokes, all on the lines of 'but herself she cannot save' , were unending. But she was attracting patients. To get rid of Phyllida and her persistent customers – no one in the house would object. Yes, one, Sylvia, whose attitude towards her mother was now maternal. She worried about her. And to what end would be Phyllida's moving out? Only useful if Frances would move down, or if Colin did. Why should they? And there was something else, very strong, which Wilhelm only guessed at. Julia's dream was that when Sylvia married or found ' a partner'-a silly phrase Julia thought – that she would move in to the house. Where? Well, Phyllida could leave the basement, and then...

Wilhelm began saying that he had at last understood: Julia did not really want him there. ‘I have always loved you more than you have loved me. ' Julia had never thought about this love to weigh and measure it. Simply, it was what she relied on. Wilhelm was her support and her stay, and now she was getting old (which she felt she was, despite Doctor Lehman), she knew she could not manage without him. Did she not love him then? Well, certainly not, compared with Philip. How uncomfortable this line of thought was, she did not want to go on with it, nor to hear Wilhelm's reproaches. She would have liked him to move in, if things hadn't been so difficult, if only to soothe her conscience over that big under-used place of his. She was even prepared to contemplate cuddles and bedtime conversations in her once connubial bed. But she had only shared her bed with one man in her long life: too much was being asked of her – wasn't it? Wilhelm's reproaches became accusations and Julia cried and Wilhelm was remorseful.

Frances was planning to leave Julia's. At last she would have her own place. Now that there were no school or university fees, she was actually saving money. Her own place, not Johnny's, or Julia's. And it would have to accommodate all her research materials and her books, now divided between The Defender and Julia's. A large flat. What a pleasant thing it is to have a regular salary: only someone who has not enjoyed one can say this with the heartfelt feeling it deserves. Frances remembered freelancing and precarious little jobs in the theatre. But when she had achieved enough money for the substantial down-payment, then she would resign from what she felt as an increasingly false position at The Defender, and that would be the end of regular sums arriving in her bank account.

She had always done most of her work at home, had never felt herself to be part of the newspaper. That she just came and went was her colleagues' complaint about her, as if her behaviour was a criticism of The Defender. It was. She was an outsider in an institution that saw itself as beleaguered, and by hostile hordes, reactionary forces, as if nothing had changed from the great days of the last century when The Defender stood almost alone as a bastion of wholesome open-hearted values: there had been no honest good cause The Defender had not defended. These days the newspaper championed the insulted and the injured, but behaved as if these were minority issues, instead of – on the whole -'received opinions'.

Frances was no longer Aunt Vera (My little boy wets his bed, what shall I do?), but wrote solid, well-researched articles on issues like the discrepancy between women's pay and men's, unequal employment possibilities, nursery schools: nearly everything she wrote was to do with the difference between men's situation and women's.

The women journalists of The Defender were known in some quarters, mostly male (who saw themselves increasingly as beleaguered by hostile female hordes), as a kind of mafia, heavy, humourless, obsessed, but worthy. Frances was certainly worthy: all her articles had a second life as pamphlets and even as books, third lives as radio or television programmes. She secretly concurred with the view that her female colleagues were heavy-going, but suspected she could be accused of the same. She certainly felt heavy, weighed down with the wrongs of the world: Colin's accusation had been true enough: she did believe in progress, and that a stubborn application in attacking unfairness would put things right. Well, didn't it? At least sometimes? She had small triumphs to be proud of.But at least she had never flown off into the windy skies of the so fashionable feminism: she had never been capable, like Julie Hackett, of a fit of tearful rage when hearing on the radio that it was the female mosquito that is responsible for malaria. 'The shits. The bloody fascist shits.’When at last persuaded by Frances that this was a fact and not a slander invented by male scientists to put down the female sex — 'Sorry, gender' – she quietened into hysterical tears and said, 'It's all so bloody unfair.' Julie Hackett continued dedicated to The Defender. At home she wore The Defender aprons, drank from The Defender mugs, used The Defender drying-up cloths. She was capable of angry tears if someone criticised her newspaper. She knew Frances was not as committed — a word she was fond of — as she was, and often delivered little homilies designed to improve her thinking. Frances found her infinitely tedious. Aficionados of the prankish tricks life gets up to will have already recognised this figure, which so often accompanies us, turning up at all times and places, a shadow we could do without, but there she is, he is, a mocking caricature of oneself, but oh yes, a salutary reminder. After all, Frances had fallen for Johnny's windy rhetoric, been charmed out of her wits by the great dream, and her life had been set by it ever since. She simply had not been able to get free. And now she was working for two or three days a week with a woman for whom The Defender played the same role as the Party had done for her parents, who were still orthodox communists and proud of it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sweetest Dream» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sweetest Dream» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.