But Lockhart reassured him. 'If I'm right there will be no need for any man to risk his life and health down a coal mine ever again. One would simply install a self-propelling machine that emitted the right frequency and it would be followed by a sort of enormous vacuum cleaner to suck the dust out afterwards.'

'Aye, well I dare say there's something to be said for the idea,' said Mr Dodd. 'It's all there in the Bible had we but known it. I've always wondered how Joshua could bring down the walls of Jericho with a wee bit of a horn.'

Lockhart went back to his laboratory and began work on his sonic coal extractor.

And so the summer passed peacefully and the Hall once again became the centre of social life in the Middle Marches. Mr Bullstrode and Dr Magrew still came to dinner but so did Miss Deyntry and there were other neighbours whom Jessica invited. But it was late November when the snow lay in thick drifts against the dry-stone walls that she gave birth to a son. Outside the wind whistled and the sheep huddled in their stone shelters; inside all was warmth and comfort.

'We'll name him after his grandfather,' said Lockhart as Jessica nursed the baby.

'But we don't know who he is, darling,' said Jessica. Lockhart said nothing. It was true that they still had no idea who his father was and he had been thinking of his own grandfather when he spoke. 'We'll leave the christening until the spring when the roads are clear and we can have everyone over for the ceremony.' So for the time being the new-born Flawse remained almost anonymous and as bureaucratically non-existent as his father while Lockhart spent much of his time in Perkin's Lookout. The little folly perched on the corner of the high wall served as his study where he could sit and look through its stained-glass window at the miniature garden created by Capability Flawse. There at his desk he wrote his verse. Like his life it had changed and was more mellow and there one spring morning when the sun shone down out of a cloudless sky and the cool wind blew round the outside wall and not into the garden, he set to work on a song to his son.

'Gan, hinny, play the livelong day And let your ways be bonnie. I wouldna have the warld to say I left ye only money.

For I was left no father's name And canna now renew it, But face and name are aye the same And by his ways I knew it.

Some legions came, they say, fra' Spain While ithers marched from Rome But like the Wall their ways remain And make in us a home.

So dinna fash yoursel', sweet son, The name ye bear be Flawse. 'Tis so the same with everyone And no man has nie flaws.

We're Flawse or Faas but niver fause I pledge my word by God. For so the ballad is my source And my true name is Dodd.'

Down below in a warm sunlit corner of the miniature garden Mr Dodd, as happy as a skylark, sat by the pram of Edwin Tyndale Flawse and played his pipes or sang his songs while his grandson lay and chuckled with sheer delight.

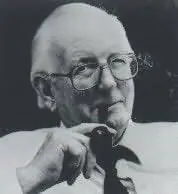

Tom Sharpe was born in 1928 and educated at Lancing College and Pembroke College, Cambridge. He did his National Service in the Marines before going to South Africa in 1951, where he did social work before teaching in Natal. He had a photographic studio in Pietermaritzburg from 1957 until 1961, when he was deported… From 1963 to 1972 he was a lecturer in History at the Cambridge College of Arts and Technology. In 1986 he was awarded the XXXIIIeme Grand Prix de l'Humour Noir Xavier Forneret. He is married and lives in Cambridge.

***