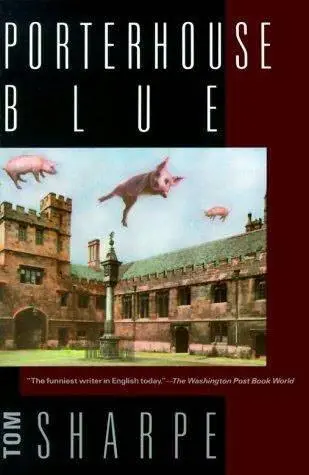

Tom Sharpe

Porterhouse Blue

The first book in the Porterhouse Blue series, 1974

It was a fine Feast. No one, not even the Praelector who was so old he could remember the Feast of ’09, could recall its equal – and Porterhouse is famous for its food. There was Caviar and Soupe a l’Oignon, Turbot au Champagne, Swan stuffed with Widgeon, and finally, in memory of the Founder, Beefsteak from an ox roasted whole in the great fireplace of the College Hall. Each course had a different wine and each place was laid with five glasses. There was Pouilly Fumé with the fish, champagne with the game and the finest burgundy from the College cellars with the beef. For two hours the silver dishes came, announced by the swish of the doors in the Screens as the waiters scurried to and fro, bowed down by the weight of the food and their sense of occasion. For two hours the members of Porterhouse were lost to the world, immersed in an ancient ritual that spanned the centuries. The clatter of knives and forks, the clink of glasses, the rustle of napkins and the shuffling feet of the College servants dimmed the present. Outside the Hall the winter wind swept through the streets of Cambridge. Inside all was warmth and conviviality. Along the tables a hundred candles ensconced in silver candelabra cast elongated shadows of the crouching waiters across the portraits of past Masters that lined the walls. Severe or genial, scholars or politicians, the portraits had one thing in common: they were all rubicund and plump. Porterhouse’s kitchen was long established. Only the new Master differed from his predecessors. Seated at the High Table, Sir Godber Evans picked at his swan with a delicate hesitancy that was in marked contrast to the frank enjoyment of the Fellows. A fixed dyspeptic smile lent a grim animation to Sir Godber’s pale features as if his mind found relief from the present discomforts of the flesh in some remote and wholly intellectual joke.

“An evening to remember, Master,” said the Senior Tutor sebaceously.

“Indeed, Senior Tutor, indeed,” murmured the Master, his private joke enhanced by this unsought prediction.

“This swan is excellent,” said the Dean. “A fine bird and the widgeon gives it a certain gamin flavour.”

“So good of Her Majesty to give Her permission for us to have swan,” the Bursar said. “It’s a privilege very rarely granted, you know.”

“Very rare,” the Chaplain agreed.

“Indeed, Chaplain, indeed,” murmured the Master and crossed his knife and fork. “I think I’ll wait for the beefsteak.” He sat back and studied the faces of the Fellows with fresh distaste. They were, he thought once again, an atavistic lot, and never more so than now with their napkins tucked into their collars, an age-old tradition of the College, and their foreheads greasy with perspiration and their mouths interminably full. How little things had changed since his own days as an undergraduate in Porterhouse. Even the College servants were the same, or so it seemed. The same shuffling gait, the adenoidal open mouths and tremulous lower lips, the same servility that had so offended his sense of social justice as a young man. And still offended it. For forty years Sir Godber had marched beneath the banner of social justice, or at least paraded, and if he had achieved anything (some cynics doubted even that) it was due to the fine sensibility that had been developed by the social chasm that yawned between the College servants and the young gentlemen of Porterhouse. His subsequent career in politics had been marked by the highest aspirations and the least effectuality, some said, since Asquith, and he had piloted through Parliament a series of bills whose aim, to assist the low-paid in one way or another, had resulted in that middle-class subsidy known as the development grant. His “Every Home a Bathroom” campaign had led to the sobriquet Soapy and a knighthood, while his period as Minister of Technological Development had been rewarded by an early retirement and the Mastership of Porterhouse. It was one of the ironies of his appointment that he owed it to the very institution for which he professed most abhorrence. Royal Patronage, and it was perhaps this knowledge that had led him to the decision to end his career as an initiator of social change by a real alteration in the social character and traditions of his old College. That and the awareness that his appointment had met with the adamant opposition of almost all the Fellows. Only the Chaplain had welcomed him, and that was in all likelihood due to his deafness and a mistaken apprehension of Sir Godber’s full name. No, he was Master by default even of his own convictions and by the failure of the Fellows to agree among themselves and choose a new Master by election. Nor had the late Master with his dying breath named his successor, thus exercising the prerogative Porterhouse tradition allows; failing these two expedients it had been left to the Prime Minister, himself in the death throes of an administration, to rid himself of a liability by appointing Sir Godber. In Parliamentary circles, if not in academic ones, the appointment had been greeted with relief. “Something to get your teeth into at last,” one of his Cabinet colleagues had said to the new Master, a reference less to the excellence of the College cuisine than to the intractable conservatism of Porterhouse. In this respect the College is unique. No other Cambridge college can equal Porterhouse in its adherence to the old traditions and to this day Porterhouse men are distinguished (sic) by the cut of their coats and hair and by their steadfast allegiance to gowns. “County come to Town,” and “The Squire to School,” the other colleges used to sneer in the good old days, and the gibe has an element of truth about it still. A sturdy self-reliance except in scholarship is the mark of the Porterhouse man, and it is an exceptional year when Porterhouse is not Head of the River. And yet the College is not rich. Unlike nearly all the other colleges. Porterhouse has few assets to fall back on. A few terraces of dilapidated houses, some farms in Radnorshire, a modicum of shares in run-down industries. Porterhouse is poor. Its annual income amounts to less than £50,000 per annum and to this impecuniosity it owes its enduring reputation as the most socially exclusive college in Cambridge. If Porterhouse is poor, its undergraduates are rich. Where other colleges seek academic excellence in their freshmen. Porterhouse more democratically ignores the inequalities of intellect and concentrates upon the evidence of wealth. Dives In Omnia , reads the college motto, and the Fellows take it literally when examining the candidates. And in return the College offers social cachet and an enviable diet. True, a few scholarships and exhibitions exist which must be filled by men whose talents do not run to means, but those who last soon acquire the hallmarks of a Porterhouse man.

To the Master the memory of his own days as an undergraduate still had the power to send a shudder through him. A scholar in his day, Sir Godber, then plain G. Evans, had come to Porterhouse from a grammar school in Brierley. The experience had affected him profoundly. From his arrival had dated the sense of social inferiority which more than natural gifts had been the driving force of his ambition and which had spurred him on through failures that would have daunted a more talented man. After Porterhouse, he would remind himself on these occasions, a man has nothing left to fear. And certainly the College had left him socially resilient.

Читать дальше