Around him the life of the College went on unaltered. Lord Wurford’s legacy helped to restore the Tower and Skullion had signed the papers with his thumbprint unprotestingly. As a sop to scholarship there were a few research fellows, mainly in law and the less controversial sciences, but apart from these concessions, little changed. The undergraduates kept later hours, grew longer hair and sported their affectations of opinion as trivially as ever they had once seduced the shopgirls. But in essentials they were just the same. In any case, Skullion discounted thought. He’d known too many scholars in his time to think that they would alter things. It was the continuity of custom and character that counted. What men were, not what they said, and looking round him he was reassured. The faces that he saw and the voices he heard, though now obscured by hair and the borrowed accents of the poor, had still the recognizable attributes of class, and if the old unfeeling arrogance had been replaced by a kindliness and gentle quality that he despised, it was still Them and Us even in the privilege of sympathy. And when an undergraduate would offer to wheel the Master for a walk, he would be deterred by the glint in Skullion’s eyes which betrayed a contempt that made a mockery of his dependence.

Occasionally the Senior Tutor would smother his revulsion for the physically inadequate and visit the Master for tea to tell him how the Eight was doing or what the Rugger Fifteen had won, and every day the Dean would waddle to the Master’s Lodge to report the day’s events. Skullion did not enjoy this strange reversal of roles but it seemed to afford the Dean some little satisfaction. It was as if this mock subservience assuaged his sense of guilt.

“We owe it to him,” he told the Senior Tutor who asked him why he bothered.

“But what do you find to say to him?”

“I ask after his health,” said the Dean gaily.

“But he can’t reply,” the Senior Tutor pointed out.

“I find that most consoling,” said the Dean. “And after all no news is good news isn’t it?”

On Thursday nights the Master dined in Hall, wheeled in by Arthur at the head of the Fellows to sit at the end of the table and watch the ancient ritual of Grace and the serving of the dishes with a critical eye. While the Fellows gorged themselves, Skullion was fed a few choice morsels by Arthur. It was his worst humiliation. That, and the fact that his shoes lacked the brilliance that his patient spit and polish had once given them.

It was left to the Dean, unfeeling to the end, to say the last word in the Combination Room after one such meal. “He may not have been born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but by God he’s going to die with one.”

In his corner by the fire the Master was seen to twitch deferentially at this joke at his own expense, but then Skullion had always known his place.

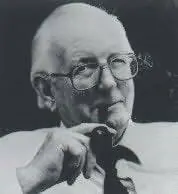

Tom Sharpe was born in 1928 and educated at Lancing College and Pembroke College, Cambridge. He did his National Service in the Marines before going to South Africa in 1951, where he did social work before teaching in Natal. He had a photographic studio in Pietermaritzburg from 1957 until 1961, when he was deported… From 1963 to 1972 he was a lecturer in History at the Cambridge College of Arts and Technology. In 1986 he was awarded the XXXIIIeme Grand Prix de l'Humour Noir Xavier Forneret. He is married and lives in Cambridge.

***