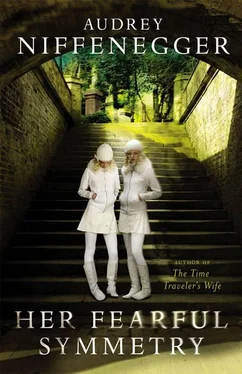

“…Julius Beer was unable to secure a position in Victorian society, because in addition to being a foreigner and Jewish, he had made his money rather than inheriting it. So he erected this rather large mausoleum where no one could possibly miss it. The Beer mausoleum blocks the view if you happen to be promenading on the roof of the Terrace Catacombs, as Victorian ladies liked to do of a Sunday afternoon.” Valentina thought of the green door in their back garden. She imagined herself and Julia wearing crinolines, strolling atop the hundreds of rotting bodies lying in the dark nasty Terrace Catacombs. Those Victorians sure knew how to have fun.

Robert led them along paths, past the Dissenters’ section; he showed them Thomas Sayers’ grave, where Lion the stone dog kept patient vigil; skipped Sir Rowland Hill, inventor of the Uniform Penny Post. He passed the Noblin family mausoleum without comment. Fifty yards on, Robert turned to say something to the group and saw that he had lost Julia and Valentina. They were standing in front of the Noblins, arm in arm, conferring. Robert parked the group in front of Thomas Charles Druce and jogged back to the twins.

“Hello,” he managed.

They went still, like rabbits looked at too directly. Valentina said, “You’re Robert Fanshaw, aren’t you?” Julia thought, What?

Robert’s stomach lurched. “Yes. That’s right.” A look passed between Valentina and Robert that Julia could not interpret. “We’ll talk after the tour, shall we?” he said, and walked with them back to the front of the group. He fumbled through Thomas Charles Druce’s exhumation, skipped murder victim Eliza Barrow and also Charles Cruft of dog-show fame. He somewhat regained his form while talking about Elizabeth Jackson and Stephan Geary, then fairly hustled the group down the Cuttings Path. Jessica was waiting for them at the gate with the green box. Robert said to her, “I’m just going to take the twins back and show them their family grave.” He half-hoped Jessica would refuse him, but she only smiled and waved him along.

“Don’t be long,” Jessica said. “You know we’re short-handed today.” As Robert walked towards Valentina and Julia he saw them framed together before the arch over the Colonnade stairs, two white statues radiant against the gloom. It seemed to him inevitable that he should meet them here.

“Come on, then,” he said. They followed him, alert and curious. He felt their eyes on him as he led them up the stairs and along the paths. The twins grew uneasy; on the tour Robert Fanshaw had seemed garrulous, eager to please; now he led them through the cemetery without comment. The sounds of the cemetery itself filled the silence: the squish of their boots on the path, the whisper and roar of the wind in the trees. Birds, traffic. Robert’s overcoat flapped behind him and Valentina recalled the retreating figure she had seen that day by the canal. She began to be frightened. No one knows we’re here. Then she remembered the duchess at the gate and felt reassured. They came to the Noblin mausoleum.

“So,” Robert said, feeling like an absurd parody of a Highgate tour guide, “this is your family’s grave. It belongs to you, and you can come and visit whenever you like, whenever the cemetery is open. We’ll make you a grave owners’ pass. There’s a key in Elspeth’s desk.”

“A key to what?” Julia asked.

“This door. You also have a key to the door between our back garden and the cemetery, though we’re asked by the cemetery staff not to use it.”

“Do you go in?”

“No.” His heart was pounding.

Valentina said, “We’ve been wondering about you. We wondered-why we didn’t see you. We thought maybe you were out of town or something-”

“Martin said you weren’t,” interrupted Julia.

“So we were confused, because Mr. Roche said you would help us…” Valentina looked up at Robert, but he was looking at his feet and it seemed like a long time before he replied.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

He was unable to look at the twins, and they pitied him, although neither was at all sure why. Julia was amazed to see this man who had been so voluble, so eager to tell them more than anyone could possibly want to know about the cemetery, now standing inarticulate and frightened. His hair hung over his face; his posture was abject. Valentina thought, He’s just very shy-he’s afraid of us. Because Valentina was shy herself-because she had spent her life with an extrovert who never tired of mocking her timidity-since she had never met a person who seemed normal and was abruptly revealed to be acutely inhibited, because there was a profound intimacy in observing Robert’s fear, because she was emboldened by Julia’s presence: Valentina stepped closer to Robert and put her hand on his arm. Robert looked at her over the rims of his glasses.

“It’s okay,” she said. He felt, without being able to express it to himself, that something lost had been restored to him.

“Thank you,” he replied. He said it quietly but with such intensity that Valentina fell in love with him, though she had no name for the feeling and nothing to compare it to. They might have stood that way for a long while, but Julia said, “Um, maybe we should go back,” and Robert said, “Yes, I told Jessica we wouldn’t be long.” Valentina felt as though the world had paused. Now it continued; they walked together side by side down the Colonnade Path.

Julia asked Robert about his thesis, and his answer carried them back to the cemetery’s gate. As they passed the office door Jessica popped out; Robert guessed that she had been watching for them. She took the twins’ hands in hers and said, “Elspeth was very dear to us all. We’re delighted to finally meet you both. I do hope you’ll come and visit often.”

“We will,” said Julia. She liked the idea of getting behind the scenes, of finding out what went on in the cemetery when the tourists left. Valentina met Jessica’s eyes and smiled. Robert was standing slightly behind Jessica, watching them. “Bye,” Valentina said as she and Julia slipped through the gate. Valentina’s face showed Robert something that filled him with apprehension-her face mirrored his own feelings. He understood and he didn’t want to know.

“Goodbye, my dears,” said Jessica. She turned the key in the lock and watched as the twins walked up Swains Lane. Why so worried? she asked herself. They’re darling. Robert had disappeared into the office. She found him counting out the change into little plastic bags.

“Are you all right?” she asked him.

“I’m fine,” he said, without looking at her. She was about to question him further when the walkie-talkie squawked out Kate’s request: more tickets for the Eastern gate. Jessica grabbed a book of tickets and left Robert to his mood. The rest of that Sunday was a blur of guides and visitors, counting receipts and closing; by the time she thought about Robert again they were standing by the Western gates, locking up.

Phil and some of the younger guides were headed up the hill to have a pint at the Gatehouse. “D’you want to come along?” Phil asked Robert.

“No,” Robert said. He wanted a drink, but he didn’t want to talk to anyone. He wanted to think about the afternoon, to relive it, to make it come out differently, to arrive at some other conclusion. “No, I think I’m coming down with something.” He turned and walked off, startling the rest of them with his abrupt departure.

“What’s eating him?” Kate asked Jessica.

Jessica shook her head. “With our Robert one never quite knows,” she replied. “It’s probably just Elspeth.” Everyone agreed that yes, it was probably Elspeth. They went up the hill to the Gatehouse and gossiped about Robert for a while, then lost interest and turned to the more urgent pleasures of trading stories about odd things that had happened that day on their tours and trying to outdo each other in their knowledge of obscure cemetery anecdotes. Kate drove Jessica home, and they agreed that something was definitely amiss with Robert and that Elspeth was at the bottom of it. Having settled that, they turned their attention to Monday’s funerals.

Читать дальше