The next day, I telephoned hotel after hotel, asking for room 312 and then hoping that whoever answered would help me. Finally, on about the fifth call, I reached a room where a young woman answered and said, “Oh, is this Andrew? You must want Cheri.” Bingo!

Cheri spent almost all the rest of her vacation with me. She was the sweetest and most beautiful woman I had ever met, and I could tell we were falling in love. When the time came for her to depart, I met her in the lobby of her hotel and we waited for the airport shuttle to arrive. As the driver called for passengers, she started crying. I kissed her, told her I already loved her, and impetuously told her I believed we would get married someday. Cheri’s eyes grew wide, and she gripped me tightly. We both had been hurt in bad relationships, and as much as she wanted to believe me, it was crazy. I can’t explain it, but I already knew. She was unlike anyone I had ever met. “Just believe,” I whispered. For some reason, I knew it would happen.

Our long-distance romance took place in Denver, Raleigh, and Los Angeles, with side trips for a cruise and vacations along the California coast. Seven years younger than me, Cheri was twenty-three and had just begun a career as a traveling nurse. An agency booked her on three-month assignments that moved her from city to city so that she could see the world while making a living. After growing up in a small town in southern Illinois, she was pursuing the life of adventure she wanted. It was full of new friends, new sights, and new experiences. She was not ready to fall in love or settle into a serious relationship, but we had fallen head over heels.

We were so crazy in love that I skipped my family’s Christmas celebration and went to meet her family in the tiny town of Highland, Illinois. My first impression of the town was that it was small, cold, and windy-and had a lot of cornfields. When we got to her house, a gust of wind caught the door of my SUV as I opened it, and it banged me hard in the head. The blow opened an old wound, which started bleeding profusely just as her mother, father, and thirty close family members came to greet us. A bandage and some compression stopped the flow, but I wasn’t finished making an impression on my in-laws-to-be. I tossed and turned all night and finally got up early, took a walk, and bought a newspaper. As I was reading it at the kitchen table, her mother came in to cook breakfast. She lit a candle that was on the table. The paper went up in flames, singeing all the hair off my arm. Adding insult to injury, that night her mom walked in on Cheri and me as we were “making up” after having had a little spat.

Despite all the mishaps, Cheri’s family decided they liked me, which, given how close they all were, was extremely important. She and I settled into a life together in Raleigh, where we shared a little apartment in an old downtown building with huge windows, hardwood floors, and posters of Jack and Bobby Kennedy on the walls. Cheri’s favorite bit of decoration was a slogan I had found on a paper bag, cut out, and t" aut out,aped to the refrigerator. It said, “Never Confuse Having a Career with Having a Life.” To me, it meant that happiness could be found in a balance of work and love, and it seemed like a great piece of advice.

It was pretty easy to stick to the refrigerator motto in those days. Cheri worked long shifts as a nurse at the hospital-I usually drove her there and picked her up-but she had lots of days off. I put in my eight-hour days for the trial lawyers association, jogged at lunch, and at night I would cook dinner and we’d sit on the little balcony at our apartment, where we could watch the sun set over downtown. We’d spend weekends at a lake or the beach or traveling. We felt like the luckiest people in the world.

I offer all this background not to explain or excuse any choices that I made later, but to reveal, as best I can, the man I was before I tied my fate to John Edwards. I had been blessed in many ways. I had grown up in a comfortable home as the son of a prominent family who had introduced me to people and ideas that were exciting and inspiring. My mother and father both loved me and taught me that I should try to make the world a better place. I had the support of friends and extended family. I had a good big brother, two loving older sisters, a dog, and a horse. And in the community of Raleigh-Durham/Chapel Hill-known as the Research Triangle-we were respected even when my father’s more liberal ideas rubbed people the wrong way.

Life inevitably brings change, loss, and trauma to everyone. Growing up requires us to accept that people are deeply flawed and that sometimes, at least in the short run, evil seems to triumph over good. In my case, these realizations came in a shocking way as my father’s affair took away my hero, my family, and my community. I didn’t respond well at first. But in time, I recovered my equilibrium. By age thirty-two I had finished my education, started a career, and found someone to love (who also loved me), and I had begun to see a brighter future. It was the summer of 1998.

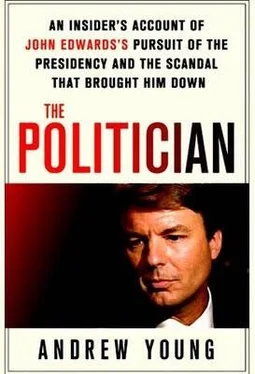

THE SPELLBINDER

That summer, the members of the North Carolina Academy of Trial Lawyers went to Myrtle Beach for a meeting where they would network, do business, and attend professional seminars at a beach-front hotel called the Ocean Creek Resort. A palm tree paradise with secluded cottages, hotel towers, pools, and a white-sand beach, the setting was ideal for a working vacation. My job would require putting on a party where the group could meet political candidates and organizing a five-kilometer road race. Otherwise, Cheri and I were free to make the long weekend into a minivacation.

We were dressed in bathing suits and flip-flops when we walked through the hotel lobby and I insisted on stopping in one of the meeting rooms to hear at least the start of a presentation by a Raleigh-based lawyer named John Edwards, who had surprised the state a month before by winning the Democratic Party’s nomination for the United States we„Senate. (Edwards had spent millions of his own dollars to defeat a big field that included favorite D. G. Martin, who had run for Congress twice before.) It was one o’clock in the afternoon; even if we wasted an hour on this talk, there would be plenty of time for the beach.

In this crowd, Edwards was a superstar. He had amassed a personal fortune in the tens of millions of dollars by suing on behalf of those who had been terribly injured by corporations, hospitals, or individual defendants. By the mid-1990s, he was so highly regarded that other lawyers jammed into courtrooms whenever he made a closing argument. His most famous case involved a little girl who barely survived after being disemboweled by the suction of a pool pump. At the end of the trial, Edwards gave a ninety-minute closing in which he evoked the recent death of his teenage son, Wade, who had been killed in a freak car accident in 1996. His performance won a $25 million verdict for his clients and solidified his legendary stature. But it was just one of more than sixty victories-totaling over $150 million-that he won in roughly a decade. This record helped him become the youngest person ever admitted to the prestigious Inner Circle of Advocates, a group comprising the top trial lawyers in the nation.

All of Edwards’s success had given him the means to do anything he wanted with his life, but he would say that it was his son’s death that pushed him toward politics. By all accounts, sixteen-year-old Wade was a smart, talented, and high-spirited young man who loved the outdoors and music, collected sports cards, and owned a future that was as bright as a star. Three weeks before he died, he had attended a White House ceremony for finalists in an essay contest. The theme for entries had been “What it means to be an American.” Wade wrote about accompanying his father to a firehouse to vote.

Читать дальше