Out on the field was the man who had once promised me the brightest future I could imagine and then abandoned me to national disgrace, hiding behind his sunglasses, talking on his cell phone and chatting with the boys on the Mariners team, including his own son Jack. The players, with big ball gloves on their hands, seemed as cute as floppy-eared puppy dogs as they chased pop flies and grounders. My former friend, who beamed at them with his world-famous smile, looked like America ’s Father of the Year, an award he actually won in 2007.

We joined the Yankees sideline, where everyone except the kids felt the tension. Cheri and I sat alone, ignored as the other parents chatted. As the innings passed, we marveled at the way our old friend and his wife-two people who had been as close as family-refused to even look in our direction. Once we would have hugged as we said hello and then spent the entire game side by side, laughing and talking. Half the people at the park would have wandered by just to say hello. A few would have asked for favors, which were granted with a simple “Call Andrew and he’ll take care of it.” And I would.

This time there were no hugs and no jokes, and no one came to ask either of us for anything. Jack and his sister Emma Claire, who used to play with our kids, looked at Cheri with confusion in their eyes. We had no idea what their parents had told them about us. We overheard one of the mothers in the crowd whisper something about “the Youngs.”

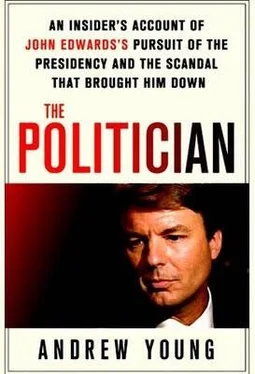

When the game ended with our guys a few runs behind (so much for an undefeated season), my old friend, boss, and mentor walked the long way to his car so he could avoid us and everyone else. While other parents were still collecting empty juice boxes and tired little ballplayers, he and his family were halfway to their home. It was the last time I would ever see my former boss, John Edwards-once one of the most powerful politicians in the world. But it was hardly the last time I would be forced to deal with the shame, distress, and anguish that came out of my own dedicated effort to help him become president of the United States.

***

As I write this, on a sunny midsummer morning in 2009, I am waiting for the Federal Bureau of Investigation to come sweep our home for listening devices. I called them after a couple of mysterious break-ins. (They will find nothing, but they wanted to make sure we weren’t being bugged.) I’m in regular contact with the United States Department of Justice because I have just completed testimony before a federal grand jury investigating allegations of corruption in John Edwards’s recent campaign for president. After I swore an oath to tell the truth, federal prosecutors questioned me for hours about huge sums of money that had quietly changed hands, and just who knew what, when. The process of giving bess of gtestimony is what you might expect. I sat in the witness chair, and as the men and women of the grand jury scrutinized me, the prosecutors pressed me for exact information about checks that were written, the way the money was used, and the timing of events. They wanted names, dates, and amounts in very specific terms. The ordeal was grueling but also reassuring, because it forced me to recall and try to understand the people, events, and decisions that had almost ruined my life and the lives of people I love.

I found some real peace in finally telling the whole truth in the grand jury room, and I am continuing to follow this process as I write this book, which will set the record straight, and try to salvage some positive lessons from the scandal that brought down one of the most promising leaders of a generation. My critics will say I am writing this book for money. They are partly correct. The Edwards scandal has left me practically unemployable, and as a husband and father, I have serious responsibilities I can meet by publishing my story. But I also have every right after three years of silence to tell my story and clear up the many lies that have been told about me and John Edwards. I believe that anyone who cares about history and the way things work in politics has a right to the truth.

Of course, the lawyers in the office of the U.S. Attorney for North Carolina weren’t interested in my family responsibilities or my desire to make something worthwhile out of the ordeal of the last few years. They wanted to hear my story in order to resolve potentially criminal issues around the Edwards affair and its cover-up. And no one in the world knows more about these events, and more about the real John and Elizabeth Edwards, than I do. I was the man who “took the bullet” for then-candidate Edwards by falsely claiming that I had fathered the child he had with a mysterious woman named Rielle Hunter. It is an indisputable fact that I willingly participated in this ruse. I joined in the deception, and at the time, amazingly, I believed it was the right thing to do. Once the decision was made, Cheri, our children, and I went on the run with Rielle to escape the press. Flying in private jets and changing locations several times, we managed to disappear, under the direction of Senator Edwards and his biggest political backers. During this time, I arranged for Edwards and Rielle to stay in constant contact. I also played a key role in keeping the truth-about the depth of their affair, the paternity of her child, and his ongoing commitment to Rielle-from the candidate’s cancer-stricken wife.

Without knowing more of the details, anyone looking in from the outside would consider what I did and conclude that I must have been a cold-blooded schemer who was motivated by ego or greed or the desire for power. It’s true that I had hoped my sacrifice would be appreciated. Everyone who works in politics wants prestige, status, and a good salary. But when this misadventure began, I didn’t request a single specific thing. On his own, when he asked me for this favor, John Edwards did promise to tell the truth within a reasonable amount of time.

I was paid well while I was on the run, but I also took a huge risk with my reputation and my family’s future. In fact, I might have abandoned John and Elizabeth Edwards many years before, when I had proven myself as a fund-raiser, campaign aide, and overall political operative, and could have sold my services to the highest bidder. Instead I stayed with them for ten years, watchinapeears, wg others come and go on to bigger and better things. I did this for one primary reason-I believed in John Edwards and all the things he said he stood for, especially his commitment to equal rights and opportunity for all, including the people who have been traditionally pushed to the side in Southern politics. Although it might be hard to recall in the Obama era, at one time John Edwards was heralded as a potential savior for a Democratic Party that had been hammered by Karl Rove, Dick Cheney, and the conservative noise machine. Like many others, I believed he was destined to lead the party and the country.

In the beginning, and through most of our time together, John Edwards had given me an outlet for the powerful idealism that I had first felt as a small boy who sat awestruck every Sunday as my father, a big, charismatic Southern preacher, filled the prestigious Duke University Chapel with words of hope, wisdom, and inspiration. As university chaplain in the turbulent seventies, the Reverend Bob Young challenged prejudice and small-mindedness in a booming voice that was one part professor and one part Bible-thumping preacher. He confronted a comfortable white congregation with the legitimate grievances of the poor, blacks, and women. But he also offered hope and understanding. “Accept your mistakes, errors, failures, sin,” he said one Sunday. “Acknowledge them, know them, and live.”

When my father was pastor, the formerly staid chapel welcomed to the pulpit greats of the civil rights movement like Martin Luther King Jr. and heroic leaders like Terry Sanford. A former governor, president of Duke, and U.S. senator, Sanford was once John Kennedy’s choice to replace Lyndon Johnson as vice president in 1964. I often sat on his lap at the chapel while a thousand people listened in rapt silence to my father’s message. No experience could have been more inspiring. As light streamed in through stained glass and the great pipe organ literally shook the pews with sound, I learned to imagine myself as a part of something bigger. My father, Terry Sanford, and their friends had been involved in the civil rights movement and had witnessed and participated in historic events. Their stories gave me chills.

Читать дальше