Henry made an attempt at an apology. "What I meant is you're comfortable with animals. You know them. Whereas people, people are strange and unreliable. That's what I meant."

The taxidermist turned and unlocked the door of his store without saying a word. They entered. There in the gloom, hidden and quiet, anxiously awaiting his return, were all his animals. He flicked a few switches and the light seemed to bring them to life. The taxidermist was visibly relieved to be back in his store. He headed for the back room. Henry lingered as Erasmus settled on the floor next to the front counter. The dog seemed out of sorts, Henry noted in passing.

When Henry entered the workshop, the taxidermist was already at his desk. Henry took his usual place on the stool. The taxidermist was not to be put off finishing what he was saying. He said it more freely now.

"After the incident reading the paper in the cafe, Virgil bemoans how his feelings have shrivelled. He corrects himself: he says that one feeling has expanded-fear-while all the others have shrivelled. Intellectual thrill, aesthetic rejoicing, quiet appreciation, fond recollection, witty banter-these have all been crowded out by fear, leaving him dull-eyed and indifferent most of the time. Were it not for Beatrice being in his life, Virgil says, he would feel nothing at all. Everything, even fear, nearly, would be shrugged off. He would be a wandering corpse, a bundle of mindless functions, like a house without its inhabitants. He says that, and then he remembers the landscape of the previous evening, how moved he was by it. Considering his circumstances, this astounds him, that he was moved by a wind and a few fields. Like taking a moment in a museum on fire to appreciate a fine landscape painting."

Henry wondered if the taxidermist didn't live in his store, not above it or nearby, but actually in it. He looked at Virgil and Beatrice, nearly said hello to them. He was starting to know them well.

The taxidermist went on, uninterruptible.

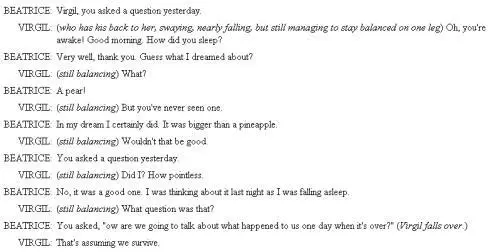

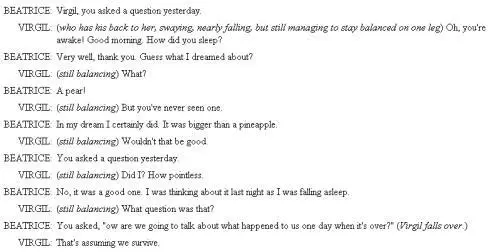

"He's so elated at this unexpected burst of feeling that for nothing, for joy, he gets up and cartwheels himself onto his hands. He examines the landscape upside down. He leans to one side and holds himself up in the air on a single arm, which is easy for him. After a moment, he returns onto all fours and he does the same balancing act with his legs, first standing on both and then getting onto just one. That's a harder trick for a howler monkey. They're not normally bipedal. His two arms shake, his raised leg trembles, his tail jerks about in the air. And that's when Beatrice wakes up and asks him the key question of the play."

He searched on his desk. Henry couldn't see why the taxidermist's pages had to be so scattered. He was forever shuffling through them. Why didn't he have them in order? It was a play, after all, a sequence of scenes that should follow some narrative logic.

"Here, I found it," the taxidermist said. And he read-aloud, of course:

"That's the key question in the play, how they are going to talk about what happened to them. They come back to the question again and again."

"And to answer the question I asked you at the cafe," Henry broke in, "about what happens in the play, in effect what happens is they talk about talk."

"I think of it as talking about memory."

If Henry hadn't seen it earlier, he was starting to see now where the problem lay with the taxidermist's play, why he needed help. There seemed to be essentially no action and no plot in it. Just two characters by a tree talking. It had worked with Beckett and Diderot. Mind you, those two were crafty and they packed a lot of action into the apparent inaction. But inaction wasn't working for the author of A 20th-Century Shirt.

Henry wanted the taxidermist to explain his play, but he didn't want to be the first to invoke the Holocaust. He thought the taxidermist would be more forthcoming if he brought it up himself.

"Let me ask you a simple question: what's your play about?"

As soon as the question had left Henry's lips, the irony of it leapt to his mind. It was the same question the historian had asked him during that terrible lunch in London nearly three years ago, the question that had gutted and silenced him. And here he was asking it himself. But the taxidermist had no problem dealing with it. He practically shouted his answer.

"It's about them!" His hand violently swept the room.

"Them?"

"The animals! They're two-thirds dead. Do you not understand that?"

"But-"

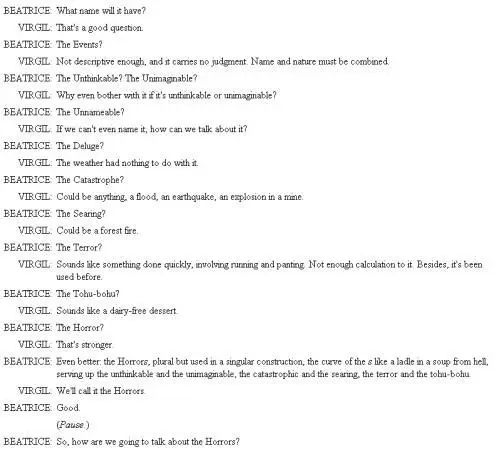

"In quantity and in variety, put together, two thirds of all animals have been exterminated, wiped out forever. My play is about this"-he searched for words-"this irreparable abomination. Virgil and Beatrice call it-wait!"

The vehemence and conviction of his tone took Henry aback. The taxidermist dove into his papers again. For once he found what he wanted quickly:

"You see, the question comes back again and again. Virgil and Beatrice set up a list, a very important list. Here, look."

The taxidermist abruptly got up from behind his desk. Henry stood up with him. The taxidermist came round to Beatrice. Placing one hand on Virgil's rump and the other under his bent leg, he lifted Virgil off Beatrice's back. He placed him on the desk.

"Look," he said again.

He was pointing at Beatrice's back. Henry looked. All he could see was thick donkey hair, a little matted here and there. The taxidermist went to get his light. When he shone it on her back, Henry could see a vague pattern in the way the hair was matted.

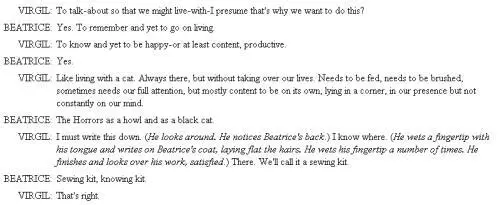

"It's the list," the taxidermist said. "Because they live in a country called the Shirt, they call it their sewing kit. Virgil starts writing on Beatrice's back with a wet fingertip a list of all the ways they come up with of how to talk about the Horrors."

Henry looked closely at Beatrice's coat. There was no way that spit and hair could spell anything on a donkey's back, he thought, certainly nothing that would survive the course of an ordinary day, but it was no doubt another of the taxidermist's symbols.

"The first item in the sewing kit is a howl. Beatrice gets the idea from hearing Virgil the previous night. The second item is a black cat."

"A black cat? How is a black cat a way of talking about the Terrors?"

"The Horrors. Like this."

The taxidermist carefully resettled Virgil on top of Beatrice and went back to his papers. Henry mused that it would be so much easier if he could get the play into his own hands and read it. He realized that he was close to thinking "and write it."

The taxidermist found a page and read from it:

"It's symbolic again," the taxidermist said.

"Yes, I understand that. But all this talking. In a play, as in any story, there must be-"

"There's silence too. At one point Virgil says that words are just 'refined grunts.' 'We overvalue words,' he says. After that, they try to talk about the Horrors by other means, through gestures and sounds and facial expressions. But it exhausts them. The scene is right here in front of my eyes."

He launched forth:

"You see, it's not just words. There's also noise and silence. And there are gestures too. Like this one. Virgil and Beatrice put this one in their sewing kit."

Читать дальше