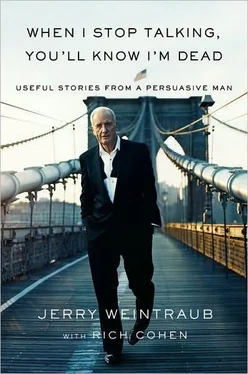

She was so wise, so wonderful.

"What about the children?" I asked. "What about the grandchildren?"

"We will talk to the children and grandchildren," she said. "I will explain it to them. I will say, 'Look, there is no reason for animosity. I am fine with this, you should be fine with it, too. There is no reason for you not to be friendly with Susie or close to Susie.' "

And that's what we did. We sat with the children and grandchildren, and told them, and they were all right with it. We told our friends, and some could not understand and were terribly bothered about this arrangement-okay, you are not us, you don't have to live like us.

The simple fact is, Jane no longer wanted my life. She didn't want to go to parties, didn't want to have sex with me. Not interested. Good. She needs what she needs and I need what I need, which is to be with somebody who wants to be involved in every part of my life: mentally, emotionally, sexually. Warren Beatty, lothario of lotharios, once asked me the secret. "How did you make it work, Jerry? How do you pull it off?"

Well, the answer is, I didn't. Jane and Susie did. I have a life with Susie and I love Susie, but I'm still with Jane, too. I see her all the time, and we're on the phone constantly. I will be there whenever she needs me. Otherwise, I am off, in my own life. I think this works only because Jane had such a long and successful career. She was a singer, she was a star, she was a mother. She had many lifetimes without me and I have had many lifetimes without her. She never lived through me. We used to live together; now we live apart. When marriage was invented, people didn't live very long. When I was a kid, if a couple had a fiftieth wedding anniversary, they were ancient. Nowadays, with the medicine and the longevity we have, when you marry somebody, you are in it for a very, very long time. I don't know if that's the way it's supposed to be. It's not for me, anyway. I have been with Jane for forty-eight years. I'm one of the ancients now. But I am still here, which means I am still living, still changing.

I later learned that Susie descends from Hollywood royalty. Her mother's godmother was Fanny Brice. Her mother's father was an Academy Award-winning writer. Her father was Bud Ekins, the legendary stuntman. Bud always had a passion for motorcycles. Wheels, crankshafts, throttles-he could not get enough. He used to ride wide open, burning up the desert east of LA. He was a legend in the racing world. In the 1960s, he won four gold medals at the Six-Day Trials in France and England. He won or came close to winning dozens of races in America and all over the world. He was known as the desert fox, a charismatic star, cool before that attitude went mainstream, tough as hell, with a cigarette forever hanging from the corner of his mouth.

His motorcycle shop in LA-he sold Triumphs-was a haunt of leather-clad riders and wannabes, including young movie stars eager to soak up Bud's authenticity. Steve McQueen was a regular, hanging around the garage talking to Bud, who, in his greasy white T-shirt, grimaced and said, "Yeah, yeah, hand me that spring hook over there." When McQueen was shooting The Great Escape, he asked Bud if he would be his stuntman double. It was Bud Ekins who, on a Triumph TR6, performed the famous jump that carried Steve McQueen over a wall of concertina wire. Bud was sought out after that. He appeared in dozens of films and TV shows: racing a Mustang up and down the streets of San Francisco in Bullitt, running a motorcycle up the stairs of the fraternity house in Animal House, doubling for Ponch in the more hair-raising sequences of Chips.

I got an incredible kick out of Bud: the way he looked and walked, how he went at each insane stunt with a carefree ease. I want to make a movie about him, a biopic, in which he will be played by Brad Pitt, because who is the star really, the man who stood for the movie still, or the man who cleared the concertina wire?

Bud was an older man when I knew him, ailing from a life of machines, whiskey, and cigarettes. I sat with him in the hospital when he was sick. I loved the guy. He was a Catholic, so a priest went into his room, but he did not want a priest.

I asked him why.

"Why?" he said. "Because I don't want to confess all the shit I did, that's why."

He asked about rabbis. "When they come, do you have to tell them everything?"

"Nah," I said, "you don't have to tell them anything."

Soon after that he told me he wanted to convert to Judaism. "'Cause you're a Jew and Susie is a Jew," he said. (Susie converted.) "And I figure I'm whatever you guys are. Also the confession stuff."

I gave a eulogy at Bud's funeral. I spoke of how he had decided to become a Jew. Many of the mourners looked confused. These were stuntmen and bikers, hundreds of tough guys with long hair and leather coats, giant guys named Tiny. "Let me explain why he became a Jew," I said. "Because Bud Ekins did not want to confess his sins." With that, the stuntmen and bikers went wild, hooting and cheering, a good send-off for a great man.

No matter how old you are, everything changes when your parents die. The wall between you and death collapses; suddenly gone are the only people who could speak with true authority. My life has been spent chasing mentors, each of them being like a substitute parent, but when your real parents die, you realize certain things are irreplaceable. They go and never come back. It's a blow. This is what it means to be an orphan.

My mother got sick first. By this time, I'd been sick myself, with prostate cancer. I won't go into detail, except to say it reminded me of the fragility of life. We are all walking on a wire. The key is to behave as if you will live forever. Her first symptoms presented themselves as anxiety or forgetfulness. This was in the late 1980s. She was still my mother, still the same woman with the same face and hands, but the curtain was coming down. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer's. Each day was a little worse than the day before. She got lost in her own neighborhood, then her own house, then her own mind. She couldn't recognize friends and family. It was very hard on my father. Here was this woman, the great love of his life, sitting next to him as always, but already gone. It was obvious to me that something had to be done; the situation could not go on. My father could not make that decision because it was too painful. My brother could not do it because he was too close. Distance allowed me to see the situation more clearly. I flew to New York, went to the apartment, took my mother to the Riverdale Home for the Aged. When my father objected, I said, "This is what we're doing." It was the most painful day of my life. My father went over there every morning, did what he could, watched her fade-God knows what he was thinking.

She died on April 30, 2000. I stood at her graveside, said the prayers, and cried. A man without a mother is a man without a country, an exile. You never recover from it. My mother was the Bronx and the family and the streets at sundown and the merchants in the shops and the smoke and the smell of cooking and the train rattling over Jerome Avenue, the safety and love of family, everyone at the table, the world when the world was whole.

My father was now alone for the first time in more than fifty years. He did not talk about what was going on inside him, how he felt, any of that. That was his generation-they worked for us, gave up their lives and bodies for us, without a whisper of regret or complaint. My brother and I went on with our lives, too. It's the way with the titanic events, a death in the family, the loss of an indispensable person. The world should end, but it does not. It goes on, and carries you with it.

About eight weeks after the funeral, I was in Kennebunkport with Jane. I tend to get bored in Maine, and spend most of the time driving around. One morning, as we passed a Ford dealership, I said to Jane, "I want to buy a new car."

Читать дальше

![Сьюзан Кейн - Quiet [The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking]](/books/33084/syuzan-kejn-quiet-the-power-of-introverts-in-a-wo-thumb.webp)