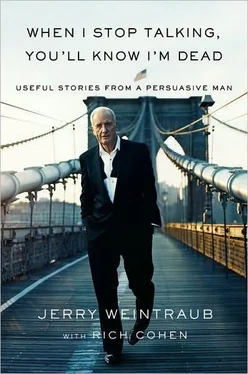

I rented offices in West Hollywood. The rooms had floor-to-ceiling windows through which you could see hills and cars moving in the canyons. There was art on the walls, shag on the floors, Perrier in the refrigerators, no expense spared. People judge on first sight, so make those surfaces shine. If you want to be seen as a major, look like a major. As a great man said, perception is reality. As another great man said, You grow into the suit. As a philosophy this means operating on confidence, in the belief that something will happen, that the trick will work, that the backup will arrive with the heavy guns. It's how America has operated from the beginning.

I hired a staff, recruiting talent from studios and agencies all over town. What these people had in common was a belief that we could accomplish what had not been accomplished in a generation-the creation of a new factory. These were, for the most part, established executives, men and women with families and careers behind them, meaning they were experienced and knowledgeable, and also meaning they were expensive. I suddenly found myself mired in a sea of health plans and pension benefits. In this way, we accrued a great mountain of debt before the first writer was contracted or the first scene was filmed. If I had known what to look for, I would have seen it in the early balance sheets-money going out (left pocket) versus money coming in (right pocket)-a terrible premonition

The company existed for less than four years. In this time, we made a handful of movies-these were distributed by Columbia Pictures-including Fresh Horses, The Big Blue, and My Stepmother Is an Alien. I promoted these films every way I knew how-George Bush, then president, was at the premiere of My Stepmother Is an Alien, generating a shower of publicity. But the trouble was evident early on. What makes a major a major is its ability to float a sea of debt. This is needed less to make movies than to weather flops. You need enough not merely to survive one dud, but to survive a season of duds, a worst-case scenario not at all infrequent in the business. In the case of a small studio, even one that has been well financed, the margin of error shrinks. With each flop, debt accrues and pressure grows. Each new movie is more important than the last. As the stakes increase, so does the fear, until the mood in the office and on the sets becomes intolerable, exactly the wrong atmosphere in which to make a movie. There was bickering and second-guessing; some people quit, others were fired. Part of it had to do with bad luck-a movie opened at the wrong time, it rained that weekend, and so forth-part of it had to do with bad planning. If I had known two years would go by without a hit, I might have made fewer films-but most of the problems resulted from a basic flaw: The movies were not very good.

This, in turn, resulted from a still more fundamental error, a flaw in the very conception of the business: I loved making movies, which resulted in hits, which increased my love, which sparked a desire for control, which caused me to start my own studio, which-and here is the paradox-took me out of the movie business and put me into the company running business, occupied not with writers and artists, but with health-care plans, office rivalries, and infighting. I had, in a sense, promoted myself right out of the job I always wanted, which was telling stories, producing. I lost touch with the films, which were now being made for me instead of by me and thus were no longer Jerry Weintraub Productions.

Of course, if the movies had been good, if they had drawn audiences, if they'd had kids doing the crane kick in the parking lot, everything else would have taken care of itself. But the movies were not good. I realized this little by little, then in a great rush. Success had caused me to cease doing what made me successful. More important, it had caused me to stop doing what I loved. I recall this period reluctantly. People say you learn more from failure than success; it's true. From this period, which runs like a ridgeline between my middle years and my true adulthood, I learned the great lesson of business: If you find something you love, keep doing it.

A business fails like a levee or a body fails. Everything is okay until it's not. There is a break, a wall caves in, the flood rushes through. For us, this meant debts we could not repay, movies we could not finish, bonds we could not redeem. I take full responsibility for this. It was all my fault. Did I feel sorry for myself? You bet. I was drowning in self-pity. It felt like I was watching this beautiful edifice I had constructed over the course of a career wash away at the first high tide. The banks were involved, the creditors were involved, the government was involved. When it was over, the company was gone. I was fifty years old. I had lost $30 million.

When the pressure was too great, I got on a plane and went to Florida. I wanted to be out on the water, the horizon ringed by water, the sun on the water and a line taut with a big fish. My mind was reeling. I did not know what to do, or where I would go next.

Luckily for me, I had a father, and he was a piece of steel. I went to see him. I was in tears, a grown man crying real tears. I said, "Oh, Pop, you got to help me. Look what happened. Look how hard I have fallen. Look how much I lost. I have troubles, real troubles. I've made such a failure, Pop, such a terrible failure."

Here's what he said: "You've got troubles, kid? Real troubles? Well, I tell you what. Put your troubles in a sack. Bring them to the end of the road, where you will find a lady in a store filled with sacks. She will take your sack of troubles and, in return, let you leave with any sack you want."

In the end, I was saved by my friends, all the people I had known and worked with over the years. Barry Diller, Michael Eisner, Steve Ross, Bob Daly, who was the co-CEO of Warner Bros., Terry Semel, Sid Sheinberg, who was the chief operating officer of MCA, Lew Wasserman, the people who ran the studios, they all backed me up and supported me. It was not just that they offered me jobs and opportunities, which they did, but that they showed confidence in me, and were certain I would make it all the way back. I especially remember a conversation I had with Steve Ross, who was the CEO of Warner Communications. "What are you worrying about?" he said. "You are a talented guy. That talent did not go away. The company went away? So what! Companies always go away. They're a dime a dozen. It's talent that counts!"

I was soon back in business, working from a bungalow on the lot at Warner's, where I had signed a contract to make movies. I don't care if you get flattened a thousand times. As long as you get up that thousand-and-first time, you win. As Hemingway said, "You can never tell the quality of a bullfighter until that bullfighter has been gored."

Once upon a time, I went to school to be an actor, another borough boy just home from the service. Through this window, you see me on a stage, trading punches with James Caan. Through that window, you see me running out of Capezio empty- handed, the vision of me in tights hot in my mind. I thought my career in front of the cameras had come to an end before it started, but I would eventually appear in several movies, acting work becoming a subgenre in my career. I have played myself in various films, some of my own (Vegas Vacation, Ocean's Eleven, Twelve, Thirteen), some made by friends (Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, Full Frontal). I learned to act only when I learned how to be myself, which is, of course, another kind of character. In short, I learned how to act-and I am not saying I'm a good actor, only that I'm comfortable in front of a camera-after I learned how to stop acting. When Martha Graham told me to walk across the floor, I was aware that I was a kid acting like he was crossing the floor. Now that I am an old man, I can simply cross the goddamn floor without thinking too much about it.

Читать дальше

![Сьюзан Кейн - Quiet [The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking]](/books/33084/syuzan-kejn-quiet-the-power-of-introverts-in-a-wo-thumb.webp)