"What the hell is happening?" I asked.

"We have to ask the Buddha what to do," he said.

He rubbed the Buddha's belly. He was such a con man. He said, "Tell me, O great Buddha, do you think we should keep Jerry Weintraub? Or should we let him go?"

He closed his eyes, as if he were meditating, communicating with the sages, then said to me, "The Buddha hasn't made up his mind yet."

The Colonel mumbled something, leaned in as if he was listening, then said, "It's the opinion of the Buddha that if you apologize in front of the boys all will be forgotten and it will be as it was before."

"I'm not apologizing," I said. "Tell that to the Buddha."

"You're not apologizing?"

"That's right. Tell the Buddha."

The Colonel closed his eyes, mumbled, nodded.

"The Buddha is very angry," he told me. "The Buddha says, 'Take Jerry Weintraub to the airport.' "

He blew out the candles and closed the cabinet. We went down to the van. The boys rode along. We got on the highway. I had my luggage and everything. We drove through town, past the arena. The Colonel was watching me, waiting for me to buckle. I did not buckle. I stared straight ahead. We saw the first signs for the airport. "All right, all right," he said. "Pull over."

The van stopped; the Colonel jumped out.

"Come on," he told me. "We need to talk."

He said, "Look, Jerry. You have to apologize. You have to say you were wrong. In front of everybody. All these boys work for me, and what you are doing can destroy everything."

"But I wasn't wrong," I told him. "I just wanted to have my breakfast alone."

"It's important to me that you apologize," he said. "Do it for me and later on I will do something for you."

"Fine," I told him. "What do you want me to say?"

"I want you to say that you are sorry, that you made a mistake, and that you shouldn't have done what you did."

"But I didn't do anything."

"It doesn't matter. Just say it."

We got back into the van and went to the arena. When we got out, with all the boys standing around, the Colonel said, "Jerry has something he would like to say."

"I am sorry," I told them, "I made a mistake, I should not have done what I did, and I will never do it again."

But I used that promise, the Colonel's price-"Do it for me and later on I will do something for you"-many times over the years. There is a lesson in this: Let the other guy save face with his people, but keep score.

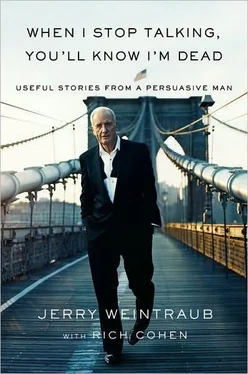

Years later, the Colonel was living in Las Vegas, working as an advisor to Hilton Hotels. He was a great man, and still he died like most men die, little by little, then all at once. He had a stroke on January 21, 1997. He was eighty-seven years old. I was a pallbearer at his funeral and gave a eulogy, paying my respects to one of the last great showmen, and, more important, to a mentor and a true friend.

Working with Elvis made me rich, taught me show business, made me a player. I did not have to hustle quite as much. Once you've established yourself, you can, to some extent, let business find you. You become a beacon, a door into a better life. "Can you do for me what you did for Elvis?" In other words, people seek you out.

One afternoon, as I was reading through contracts, or whatever-I mean, who can remember?-the telephone rang.

"Hello."

"Is this Jerry Weintraub?"

"Yes."

The voice on the other end touched a sweet spot in the back of my brain. I knew it, but was not sure from where.

"Jerry, you and I need to talk business."

"Who is this?"

"Frank Sinatra."

"Oh, come on," I said. "Who is it really?"

"This is Frank Sinatra, Jerry, but I want you to call me Francis."

Now, you have to understand, for me, yes, there was Perry Como, and the Beatles, and the Four Seasons, and Elvis, but Sinatra was it. Head and shoulders above the rest. He was my idol, who I went to see when I was not working, when I was low down and in need of a pick-me-up, and when I was flying high and wanted to celebrate. I was in love with this man, or the man he was in his music, before I ever shook his hand. More than just a performer, he was a symbol. He was Vegas and the high life, the epitome of cool, but also one of us, a kid from Hoboken, who struggled on the same streets and dreamed the same dreams. He had been challenged but persisted. He was tough, too, and did not let himself get pushed around. He was Maggio in From Here to Eternity, for godsakes! In short, he was you as you dreamed you might be. By the early seventies, when I knew him, he was beyond the recklessness of youth, the ups and downs, Ava Gardner, the feud with Warner Bros. He was in the highest realm of show business. He was royalty. Then there was his music, how he wrapped himself up in each song and turned everything into an anthem. His records became the soundtrack of your life. To this day, if you look in my car, you will find only Sinatra CDs. Which is why, when the call came like that, out of the blue, I wondered if I was being hoaxed.

"Yes, Mr. Sinatra."

"Please, call me Francis."

"Okay, Francis. How can I help you?"

"I want to meet."

"Great. When?"

"Look, kid, when I say I want to meet, that means now."

"Where?"

"Go to the Santa Monica airport. My plane is waiting. It will bring you to Palm Springs."

"I would love to, Mr. Sinatra. But it's the middle of the day. I have meetings."

"Call me Francis."

"Okay, Francis."

"Now, do what I say. Go to the airport. You will be home in time for dinner."

"Yes, Francis."

I drove to Santa Monica, got on the plane.

A driver picked me up on the runway in Palm Springs. We drove through hills studded with wood and glass houses, each turned, like a flower, toward the sun. Sinatra met me at his front door, shook my hand, brought me in. He was slender and handsome, always with a half smile, always fixing a drink, his words commented on by his famously blue eyes, which, unless he was angry or depressed, and he got very depressed, seemed to be saying, "Can you believe our lives? Can you believe how much fun we're having?" Let's say he was wearing chinos, white loafers, silk socks, and a V-neck sweater-the man could dress. We talked. This was 1972. Frank had "retired" the year before. It was one of the many retirements he announced then unannounced. He went in and out of the ring more times than Muhammad Ali. The real champions are torn: They want to go out on top, leaving an image of their best selves lingering before the public, but cannot stand to stay out of the fight.

Frank tapped my knee. "Look, Jerry," he said, "I've seen what you've done with Elvis. Very impressive. I'm thinking of coming out of retirement. Do you think I can play those same kind of rooms?"

"I don't see why not."

Of course, I would not put Sinatra in the exact same rooms where Elvis was singing. These were different performers. Elvis was for the masses, for the people in the little towns between the big towns, the great crowds that filled the fields of the state fair. Sinatra was for the Italians and Jews, for the city people. He was urban. But the point remained-I could put Frank into new joints, bigger joints, the sort of arenas where crooners had never performed.

"Well, Okay," said Sinatra, "let's say that happened: Where would you start me?"

"Frank Sinatra? Well. Frank Sinatra has to open at Carnegie Hall."

I said this quickly, decisively, as if there was no other answer; a sense of certainty is what management is selling.

"Well, yes," said Sinatra. "Carnegie Hall sounds interesting."

He stood up, walked around the room, shaking the ice in his glass. "Okay, good," he said, "let's go with this."

"Go with what?"

"I want you to book a tour," said Sinatra. "I want you to handle this tour as I come out of retirement."

Читать дальше

![Сьюзан Кейн - Quiet [The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking]](/books/33084/syuzan-kejn-quiet-the-power-of-introverts-in-a-wo-thumb.webp)