Abbey Pinnola was offered a position at Ott headquarters in Atlanta, but she refused it. She wouldn't uproot her kids, or put an ocean between them and her ex-husband in London, no matter how much she disliked the man. Her next job, she decided, would be in an industry that would never betray her. So she settled on international finance and found a post at the Milan offices of Lehman Brothers.

As for Oliver Ott, he did take a job at headquarters, where he was expected to do nothing, and he did so. He stared out his window over steamy Atlanta, wishing each day to be over. His siblings encouraged him to buy another dog at least.

He attended all the board meetings, voting however everyone demanded, even acceding to the sale of the mansion in Rome and all the paintings inside. At auction, the Modigliani went to an art dealer in New York, the Leger to a private collector in Toronto, the Chagall to a foundation in Tel Aviv, the Pissarro to a gallery in London, and the Turner to a shipping company in Hong Kong, which mounted it behind the receptionist's desk.

As Oliver's siblings debated in the boardroom, he contemplated the portrait of their grandfather. Nobody in that room had met the late patriarch. They knew only the legends: that Ott had fought in World War I and been shot, which took him out of the fighting and probably saved his life. That he'd turned a bankrupt sugar refinery into an empire. Much more was unknown. Why, for example, had Ott gone to Europe and never come back? There had been a woman at the paper, Betty, and some said Ott had had an affair with her. Was that true? She had died in 1979, and the paper's other founding partner, Leo, had passed away in 1990. Who was left to say?

Overnight, the paper disappeared from newsstands, taking with it the front-page banner, the characteristic fonts, the sports pages and the news, the business section and culture, Puzzle-Wuzzle and the obits.

The paper's most loyal reader, Ornella de Monterecchi, trooped down to headquarters to demand that closure be reconsidered. But she had arrived too late. The doorman was kind enough to unlock the vacated newsroom. He turned on the flickering fluorescent beams and left her to wander.

The place was ghostly: abandoned desks and cables leading nowhere, broken computer printers, crippled rolling chairs. She stepped haltingly across the filthy carpeting and paused at the copydesk, still covered with defaced proofs and old editions. This room once contained all the world. Today, it contained only litter.

The paper-that daily report on the idiocy and the brilliance of the species-had never before missed an appointment. Now it was gone.

To begin, I wish to record those who cannot read this. My marvelous battling grandfather Robert Philips (1912-2007) and my dear bookish grandmother Monica Roberts (1911-1996). With them, Charles Dominic Philips (1940-1955), whose memory I intend to store in this book; Nick's birthday was February 10. My uncle and childhood hero, Bernard Rachman (1931-1987). And my uncle Lionel Rachman (1928-2008), one of the most remarkable men ever to stroll into a used bookshop or a racetrack.

Next, those whom I have the fortune to thank directly. My family: wonderful parents, Clare and Jack, who have been so generous, who always surrounded me with books and ideas and such kindness. My sister Emily, the most brilliant advocate, whose astute suggestions, selfless help, and unstoppable enthusiasm have boosted me countless times. My eldest sister, Carla, a splendid ally, providing me with friendship and access to her sublime mind, full of wit and thoughtfulness. My brother, Gideon, endlessly amusing and generous, as well as my favorite columnist, wine purveyor, and Chelsea attacking midfielder. Also, Joel Salzmann, and my nieces Talia and Laura; Olivia Stewart, and my niece Tasha and my nephews, Joe, Adam, and Nat. My cousin and friend Jack Slier, as well as his father, Lionel Slier, another cousin and friend. Also, my warm thanks to Paula, Hayley, and Alicia. In London, Sandra Rachman and Mike Catsis. In Israel, Aviva Rachman and Omri Dan. And in Vancouver, Alice Philips and Greg Oryall.

Now, my friends. Ian Martin, whose humanity, mind, and uppercut have rescued me more than once. His father, Paul Martin (1938-2007), one of my favorite readers-how I'd have loved to have handed him a copy. Hetty Martin, for cups of tea, kosher duck, and other Welsh specialties. From Toronto days, Suzanne Brandreth and Stephen Yach. From New York, Ian Mader, Mareike Schomerus, and Hien Thu Dao. From Vancouver, Valerie Juniper. From Paris, Paul Geitner, Chuck Jackson, and Maureen Brown. From Ankara, Selcan Hacaoglu. From Rome, Jason Horowitz, Daniele Sobrini, Aidan Lewis, and the delightful Rizzo family: Aldo, Margherita, and Benedetta.

Finally, this book would be incomplete without the inclusion of my favorite short story, Alessandra Rizzo, whose patience, support, and affection kept me afloat while I wrote.

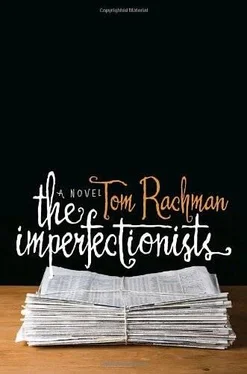

Thanks also to my agent, Susan Golomb, for fishing my manuscript from across the pond and doing such marvels with it. Also, Terra Chalberg and Casey Panell of the Susan Golomb Agency. And my editor, Susan Kamil of the Dial Press and Random House, whose wisdom and deft touch helped make The Imperfectionists that much less imperfect. My thanks also to Noah Eaker, Carol Anderson, and all those who worked on the book at Dial and Random House.

Born in London and raised in Vancouver, TOM RACHMAN is a graduate of the University of Toronto and the Columbia School of Journalism. He has been a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press stationed in Rome, with assignments that have taken him to Japan, South Korea, Turkey, and Egypt, among other places. From 2006 to 2008, he worked as an editor at the International Herald Tribune in Paris. He lives in Rome.

***