Uzaemon’s parents were prompted by the ‘Aibagawa Incident’ into finding their son a wife. A go-between knew of a low-ranking but wealthy family in Karatsu who had thriving business interests in dyes and was eager for a son-in-law with access to sappanwood entering Dejima. Omiai interviews were held and Uzaemon was informed by his father that the girl would be an acceptable Ogawa wife. They were married on New Year’s Day, at an hour judged to be fortunate by the family’s astrologer. The good fortune, Uzaemon thinks, is yet to reveal itself. His wife endured a second miscarriage a few days ago, a misfortune attributed by his mother and father to ‘wanton carelessness’ and ‘a laxness of spirit’ respectively. Uzaemon’s mother considers it her duty to make her daughter-in-law suffer in the same way she suffered as a young bride in the Ogawa Residence. I pity my wife, Uzaemon concedes, but the meaner part of me cannot forgive her for not being Orito. What Orito must endure on Mount Shiranui, however, Uzaemon can only speculate: isolation, drudgery, cold, grief for her father and the life stolen from her and, surely, resentment at how the scholars of the Shirandô Academy view her captor as a great benefactor. For Uzaemon to interrogate Enomoto, the Shirandô’s most eminent sponsor, about his Shrine’s Newest Sister would be a near-scandalous breach of etiquette. It would imply an accusation of wrongdoing. Yet Mount Shiranui is as shut to enquiries from outside the domain as Japan is closed to the outside world. In the absence of facts about her well-being, Uzaemon’s imagination torments him as much as his conscience. When Dr Aibagawa had seemed close to death, Uzaemon had hoped that by encouraging, or, at least, by not discouraging, Jacob de Zoet’s proposal of temporary marriage to Orito, he might ensure that she would stay on Dejima. He anticipated, in the longer term, a time when de Zoet would leave Japan, or grow tired of his prize, as foreigners usually do, and she would be willing to accept Uzaemon’s patronage as a second wife. ‘Feeble-headed,’ Uzaemon tells the magnolia tree, ‘cock-headed, wrong-headed…’

‘Who’s wrong-headed?’ Arashiyama’s feet crunch on the stones.

‘Yoshida-sama’s provocations. Those were dangerous words.’

Arashiyama hugs himself against the cold. ‘Snow in the mountains, I hear.’

My guilt about Orito shall dog me, Uzaemon fears, for the rest of my life.

‘Ôtsuki-sama sent me to find you,’ says Arashiyama. ‘Dr Marinus is ready, and we are to sing for our supper.’

‘The Ancient Assyrians,’ Marinus sits with his lame leg at an awkward angle, ‘used rounded glass to start fires; Archimedes the Greek, we read, destroyed the Roman fleet of Marcus Aurelius with giant burning-glasses at Syracuse, and the Emperor Nero allegedly employed a lens to correct myopia.’

Uzaemon explains ‘Assyrians’ and inserts ‘the island of’ before ‘ Syracuse ’.

‘The Arab Ibn al-Haytham,’ continues the doctor, ‘whose Latin translators named Alhazen, wrote his Book of Optics eight centuries ago. The Italian Galileo and the Dutchman Lippershey used al-Haytham’s discoveries to invent what we now call microscopes and telescopes.’

Arashiyama confirms the Arabic name and delivers a confident rendering.

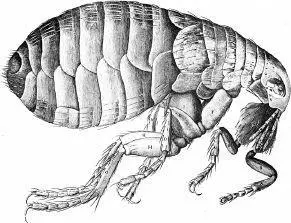

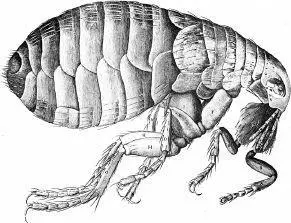

‘The lens and its cousin the polished mirror, and their mathematical principles, have evolved a long way through time and space. By virtue of successive advancements, astronomers may now gaze upon a newly discovered planet beyond Saturn, Georgium Sidium, invisible to the naked eye. Zoologists may admire the true portrait of man’s most loyal companion…

… Pulex irritans.’ One of Marinus’s seminarians exhibits the illustration from Hooke’s Micrografia in a slow arc whilst Goto works on the translation. The scholars do not notice his omission of ‘successive advancements’, which Uzaemon can make no sense of either.

De Zoet is watching from the side, just a few paces away. When Uzaemon took his place on the stage, they exchanged a ‘Good evening’, but the tactful Dutchman has detected the interpreter’s reticence and not imposed further. He may have been a worthy husband for Orito. Uzaemon’s generous thought is stained by jealousy and regret.

Marinus peers through the lamp-lit smoke. Uzaemon wonders whether his discourses are prepared in advance or netted from the thick air extemporaneously. ‘Microscopes and telescopes are begat by Science; their use, by Man and, where permitted, by Woman, begets further Science, and Creation’s mysteries are unfolded in modes once undreamt of. In this manner Science broadens, deepens and disseminates itself – and via its invention of printing, its spores and seeds may germinate even within this Cloistered Empire.’

Uzaemon does his best to translate this, but it isn’t easy: surely the Dutch word ‘semen’ cannot be related to this unknown verb ‘disseminate’? Goto Shinpachi anticipates his colleague’s difficulty and suggests ‘distribute’. Uzaemon guesses ‘germinate’ means ‘is accepted’, but is warned by suspicious glances from the Shirandô’s audience: If we don’t understand the speaker, we blame the interpreter.

‘Science moves,’ Marinus scratches his thick neck, ‘year by year, towards a new state of being. Where, in the past, Man was the subject and Science his object, I believe this relationship is reversing. Science itself, gentlemen, is in the early stages of becoming sentient.’

Goto takes a safe gamble on ‘sentience’ meaning ‘watchfulness’, like a sentry. His Japanese rendition is streaked with mysticism, but so is the original.

‘Science, like a general, is identifying its enemies: received wisdom and untested assumption; superstition and quackery; the tyrants’ fear of educated commoners; and, most pernicious of all, man’s fondness for fooling himself. Bacon the Englishman says it well: “The Human Understanding is like a false mirror, which, receiving rays irregularly, distorts and discolours the nature of things by mingling its own nature with it.” Our honourable colleague Mr Takaki may know the passage?’

Arashiyama deals with the word ‘quackery’ by omitting it, censors the line about tyrants and commoners, and turns to the straight-as-a-pole Takaki, a translator of Bacon, who translates the quotation in his querulous voice.

‘Science is still learning how to talk and walk. But the days are coming when Science shall transform what it is to be a Human Being. Academies like the Shirandô, gentlemen, are its nurseries, its schools. Some years ago, a wise American, Benjamin Franklin, marvelled at an air-balloon in flight over London. His companion dismissed the balloon as a bauble, a frivolity, and demanded of Franklin, “Yes, but what use is it?” Franklin replied, “What use is a newborn child?” ’

Uzaemon makes what he thinks is a fair translation until ‘bauble’ and ‘frivolity’: Goto and Arashiyama indicate with apologetic faces that they cannot help. The audience watch him, critically. In a low tone, Jacob de Zoet says, ‘Toy of a child.’ Using this substitute, the anecdote makes sense, and a hundred scholars nod in approval at the Franklin anecdote.

‘Had a man fallen asleep two centuries ago,’ Marinus speculates, ‘and awoken this morning, he should recognise his world unchanged in essence. Ships are still wooden, disease is still rampant. No man may travel faster than a galloping horse, and no man may kill another out of eyeshot. But were the same fellow to fall asleep tonight and sleep for a hundred years, or eighty, or even sixty, on waking he shall not recognise the planet for the transformations wrought upon it by Science.’

Читать дальше