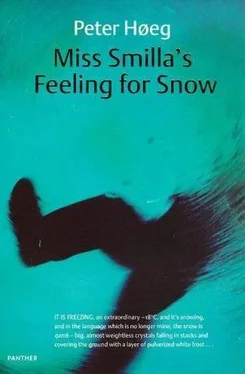

Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I hold the ice pick slightly behind me. A short distance away, out of earshot, Sonne clears off the base of the mast with the handle of his shovel.

"I know why," he says. "Because Lukas wouldn't have believed it, anyway."

"I could have pointed out Maurice's wound," I say. "A work accident. The angle grinder started going while he was changing the wheel. The chuck key struck him in the shoulder. It's been reported and explained."

"An accident. Just like the boy on the roof," I say. His face is close to mine. Its only expression is one of incomprehension. He has no idea what I'm talking about. "But with Andreas Licht," I say, "the old man on the ship, that's where things got a little more clumsy." When his body locks up, it gives the illusion that he's frozen, like the ship around us.

"I saw you on the dock," I lie. "When I swam in." While he ponders the consequences of what I've said, he gives himself away. For one second a sick animal scares at me from somewhere inside his body: Like his teeth, there is a thin veneer over the cruelty that turned him sadistic.

"There will be an investigation in Nuuk," I say. "Police and naval authorities. Attempted murder alone could get you two years. Now they'll look into Licht's death, too." He grins at me, a big white-toothed smile.

"We're not putting in at Godthåb. We're going to the tankers' floating dock. It's twenty sea miles from land. You can't even see the coast."

He gives me a quizzical look.

"You put up a good fight," he says. "It's almost too bad that you're so alone."

Part Two

The Sea

1

"I'm thinking about the little captain on the bridge up there," says Lukas. "He no longer sails a ship. He no longer exercises any authority. He's just a link in the coupling that transmits impulses to a complex mechanism."

Lukas is leaning against the railing of the bridge wing. In front of the bow of the Kronos a skyscraper of red polyenamel grows out of the sea. It looms over the foredeck and well beyond the tops of the masts. If you tip your head way back you can see that somewhere high in the gray sky even this phenomenon comes to an end. It's not a building; it's the stern of a supertanker.

When I was a child in Qaanaaq in the late fifties and early sixties, even the European clock moved relatively slowly. Changes occurred at a rate that allowed people time to register a protest against them. This rebellion first took form in the concept of the "good old days."

Nostalgia for the past was then a completely new feeling in Thule. Sentimentality will always be man's first revolt against development.

The times have made this reaction obsolete. Now a different kind of protest is needed than the lachrymose mourning for native soil. Things are happening so rapidly now that at any moment the present we're living in will be the "good old days."

"For these ships," says Lukas, "the rest of the world doesn't exist anymore. If you meet them on the open sea and try to raise them on the VHF to exchange weather reports and positions, or to ask about the ice conditions, they won't answer. They don't even have their radio on. When you displace 340,000 cubic yards of water and produce horsepower like a nuclear reactor and have a computer as big as an old-fashioned ship's chest to calculate your course and speed and maintain them or diverge from them slightly if necessary, then your surroundings cease to interest you. The only thing left in the world is your departure point and your destination and who's paying you when you reach it."

Lukas has lost weight. He has started smoking.

He might be right. One of the syndromes of development in Greenland is that everything seems to have happened recently. The Danish Navy's new heavily armed, high-speed inspection ships were recently introduced. The vote to join the Common Market and the narrow majority to withdraw as of January 1, 1985. Not long ago the Defense Ministry restricted entry permits to Qaanaaq for military reasons. And at the spot where we're now standing, everything has been newly built. The large floating oil platform, the Greenland Star, outside of Nuuk, consists of 25,000 linked metal pontoons anchored to the sea floor 2,500 feet below us. A quarter of a mile of desolate, windblown, green-painted metal, ugly as sin, twenty sea miles from the coast. "Dynamic" is the word the politicians use.

It has all been created with the goal of coercion in mind.

Not the coercion of Greenlanders. The presence of the army and the direct violence of civilization are almost at an end in the Arctic. It's no longer necessary for development. The liberal appeal to greed in all its aspects is sufficient today.

Technological culture has not destroyed the peoples of the Arctic Ocean. Believing that would be to think too highly of culture. It has simply acted as a catalyst, a cosmic model for the potential-which lies in every culture and every human being-to center life around that particularly Western mixture of greed and naivete.

What they want to coerce is the Other, the vastness, that which surrounds human beings. The sea, the earth, the ice. The complex stretched out in front of us is an attempt to do that.

Lukas's face is haggard with distaste.

"Previously, up until 1992, there was only Polar Oil at Exringehavn. A little place. A communications station and a fish cannery on one side of the fjord. The plant on the other. Managed by the Greenland Trading Company. We could dock stern-fast, up to 50,000 tons. When we got the floating hoses out we would go ashore. There was only one building for living quarters, a galley, and a pumphouse. It smelled of diesel. Five men ran the whole place. We always had a gin-and-tonic with the manager in the galley."

This sentimental side of Lukas is new to me.

"That must have been nice," I say. "Did they have clogging and concertinas, too?"

His eyes grow narrow.

"You're wrong," he says. "I'm talking about power. And about freedom. In those days the captain was the highest authority. We went ashore, and we took the crew along with us, except for the anchor watch. There was nothing at Fxringehavn. It was just a desolate, godforsaken place between Godthåb and Frederikshab. But in the midst of that nothingness, you could take a walk if you wanted to."

He gestures toward the complex of pontoons in front of us, and toward the distant aluminum barracks. "Here they have three tax-free shops and regular helicopter service to the mainland. There's a hotel and a diving station. A post office. Administrative offices for Chevron, Gulf, Shell, and Exxon. In two hours they can put together a landing strip that can handle a small jet. The gross tonnage of that ship in front of us is 125,000 tons. There is development and progress here. But no one is allowed ashore, Jaspersen. They come on board if you want anything. They check off your requests on a list, and they bring a portable chute and load your order on. board. If the captain insists on going ashore, a couple of security officers show up with a landing bridge and hold his hand until he's back on board. They say it's because of the danger of fire. Because of the risk of sabotage. They say that when the piers are full, there are 250 million gallons of oil here."

He searches for a new cigarette, but the pack is empty. "That's the nature of centralization. Under these conditions the shipmasters have virtually disappeared. Seamen don't exist at all."

I'm waiting. He wants something from me. "Were you hoping to go ashore?" he asks. I shake my head.

"Even if this was your only chance? If this was the end of the line? If we only had the return trip left?"

He wants to find out how much I know.

"We're not taking on any cargo," I say. "We're not unloading anything. This is nothing but a rest stop. We're waiting for something or other."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Рута Шепетис - Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray]](/books/414915/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between-shades-thumb.webp)