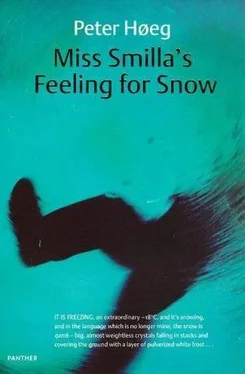

Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

You might think that someone who has never suffered or lacked anything worth mentioning would be at peace with herself. For a long time I misjudged her. I thought she and Moritz were playing a game when she walked through the room in front of us, dressed only in her little panties, and placed red silk scarves over the lamps because the light hurt her eyes, and made an endless series of appointments with Moritz and then canceled them because, she said, today she needed to see someone her own age. I thought that on some mysterious wave of self-confidence she was testing her youth and beauty and attractiveness on Moritz, who was almost fifty years older than her.

One day I witnessed her ordering him to move the furniture so that she would have room to dance, and he refused.

At first she didn't believe him. Her pretty face and slanted, almond-shaped eyes and smooth brow beneath corkscrew curls glowed with the awareness of a victory already won. Then she realized that he was not going to yield. Maybe it was the first time in their relationship. First she turned pale with rage, and then her face cracked. Her eyes became despairing, empty, abandoned; her mouth closed on smothered, infantile, despairing tears which refused to flow.

Then I realized that she loved him. That under that appealing coquettishness was a love like a military operation that would tolerate anything and fight any necessary tank battles and demand the world in return. Then I realized, too, that she might always hate me. And that she had lost in advance. Somewhere inside Moritz there is a landscape she will never reach. The home of his feelings for my mother.

Or maybe I'm wrong. Right now, at this very moment, it occurs to me that she might have won, after all. If that's the case, then I'll grant her that she put her nose to the grindstone. She didn't just leave it at wiggling her little fanny around. She didn't settle for sending lovesick glances from the stage to Moritz in the first row, hoping that it would all work out in the long run. She didn't put her trust in her influence at home in the bosom of her family. If I didn't realize it before, I know it now. That there is a raw energy in Benja.

I'm standing in the snow, pressed up against the wall of the house, peering down into the pantry. There Benja is pouring a glass of milk. Enchanting, lithe Benja. And she's handing it to a man who now steps into view. It's the Toenail.

I'm walking along Strand Drive from Klampenborg Station, and it's a wonder that I notice it at all, because I've had a hard day.

That morning I couldn't stand it any longer; I got up, tucked my hair and bandage-which is now only a Bandaid over the wound-under a ski hat, put on sunglasses and a Loden coat, and took the train to the main station, and there I called the mechanic's number, but no one answered.

Then I stroll along the docks, from the Customs Wharf to Langelinie, trying to gather my thoughts. At the North Harbor I make several purchases and pack up a box that they will deliver to Moritz's villa, and from a phone booth I make a call that I know is one of the crucial actions in my life.

And yet it's strange that it means so little. Under certain circumstances the fateful decisions in life, sometimes even in matters of life and death, are made with an almost indifferent ease. While the little things-for instance, the way people hang on to what is over-seem so important. What's important today is to see Knippels Bridge once again, where I rode with him, and the White Palace, where I slept with him, and the Cryolite Corporation, and Skudehavns Road, where we walked together, arm in arm. I call him again from the phone booth at North Harbor Station. A man answers. But it's not him. It's a controlled, anonymous voice.

"Yes?"

I hold the receiver to my ear. Then I hang up.

I page through the phone book. I can't find his car repair shop. I take a taxi out to Toftegards Square and walk along Vigerslev Avenue. There is no garage. From a phone booth I call the mechanics' association. The man I talk to is friendly and patient. But there has never been a car repair shop registered on Vigerslev Avenue.

I've never noticed until now how exposed phone booths are. Making a call is like putting yourself on display for instant recognition.

The phone book lists two addresses for the Center for Developmental Research, one at the August Krogh Institute and one at Denmark's Technical High School on Lundtofte Slope. At the latter address there's apparently a library and office.

I take a cab to Kampmanns Street, to the office of the Trade Commission. The boy's smile and tie and naivete are unchanged.

"I'm glad you came back," he says.

I show him the newspaper clipping. "You read foreign papers. Do you remember this one?"

"The suicide," he says. "Everybody remembers that. The consular secretary jumped off a roof. The man they arrested had tried to talk her out of it. The case raised a fundamental question about the legal rights of Danes abroad."

"You don't happen to remember the secretary's name, do you?"

He has tears in his eyes. "We studied international law at the university together. A wonderful girl. Ravn was her name. Nathalie Ravn. She applied for a job with the Ministry of Justice. They said-in local circles-that she might become the first female police commissioner."

"There's nothing 'local' left anymore," I say. "If something happens in Greenland, it's connected to something else in Singapore."

He gazes at me, uncomprehending and mournful. "You didn't come here to see me," he says. "You came about this."

"I'm not worth getting to know," I say, meaning it.

"You remind me of her. Secretive. And not someone you would picture behind a desk. I couldn't understand why she suddenly became a secretary in Singapore. That's a different Ministry."

I take the train to Lyngby Station and then catch a bus. In a way, it feels like when I was seventeen. You think that the despair will stop you cold, but it doesn't; it wraps itself up in a dark corner somewhere inside and forces the rest of your system to function, to take care of practical matters, which may not be important but which keep you going, which guarantee that you are still, somehow, alive.

Between the buildings the snow is three feet high; only narrow corridors have been cleared.

They haven't finished remodeling the Center for Developmental Research yet. In the lobby they've put in a counter, but it's covered up because they're in the process of painting the ceiling. I tell them what I'm looking for. A woman asks me whether I have computer time reserved. I say no. She shakes her head, the library isn't open yet, the center's archives are kept on LTNIC at Denmark's Data Processing Center for Research and Training, the computer system for institutes of higher learning, which is not accessible to the general public.

I walk around among the buildings for a while. I was here many times in my student days. Our classes on surveying were held here. Time has changed the area, made it harsher and more alien than I remember it. Or maybe it's the cold. Or just me.

I walk past the computer building. It's locked, but when a group of students comes out, I go in. In the central room there are maybe fifty terminals. I wait for a while. When an elderly man comes in, I follow him. When he sits down, I stand behind him and pay attention. He doesn't notice me. He sits there for an hour. Then he leaves. I sit down at a free terminal and press a key. The machine writes: Log on user ID? I type LTH3-just as the elderly gentleman did. The machine replies: Welcome to the Laboratory for Technical Hygiene. Your password? I type JPB. The way the elderly gentleman did. The machine replies: Welcome Mr. Jens Peter Bramslev.

When I type Center for Developmental Research the machine replies with a menu. One of the topics is Library. I type in Tørk Hviid. There is only one title. "A Hypothesis on the Eradication of Submarine Life in the Arctic Sea in Conjunction with the Alvarez Incident."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Рута Шепетис - Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray]](/books/414915/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between-shades-thumb.webp)