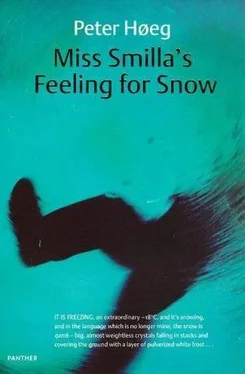

Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The clipping is from an English-language newspaper. Maybe that's why I've latched on to it. It was cut out crooked, so part of the headline is missing. It was added back on by hand, with a green ballpoint. The date is March 19, 1992. "First Copenhagen Seminar on Neocatastrophism. Professor Johannes Loyen, M.D., member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences, presenting the opening lecture."

Loyen is standing on the stage, apparently without a script or podium. It's a large hall. Behind him sit three men at a table that curves like an arc of a circle.

"Behind him Ruben Giddens, Ove Nathan, and Tork Hviid, the…"

The text has been cut off, the rest of the sentence is gone. Their typesetting machines didn't have an ø for his name. That's why it had caught my eye. That's why I remembered it.

The setting sun is glowing as I set off for home. My heart is pounding.

The minute I step through the door, the telephone rings.

It takes forever to get the red tape off. I think it must be the mechanic. He must have tried calling dozens of times.

"This is Andreas Licht." The voice is weak, as if he has a cold. "I suggest that you come at once."

I feel a surge of annoyance. Some of us never learn to take orders.

"You mean today?"

There's a strangled sound, as if he's suppressing a laugh. "You're interested, aren't you?…"

He hangs up.

I'm standing there with all my outdoor clothes on. In the dark, because I didn't have time to turn on the light. Where did he get my phone number?

I detest being rushed. I had other plans for the day.

I put down the kamiks and go back out into the Copenhagen evening.

On my way down the stairs, I stop outside the mechanic's door. I feel tempted to take him along. But I recognize the feeling as a form of weakness.

I have a felt-tip pen in my pocket but no paper. On a 50-krone note I write: "South Harbor, Svajer Wharf, Berth 126. Back later. Smilla."

This message is a compromise between my need for protection and my belief that the plans you keep secret are the ones most likely to succeed.

I take a cab to the South Harbor power plant. Maybe it's the mechanic's paranoia about phones that has infected me, but I don't want to leave a clear trail.

It's a fifteen-minute walk from the plant.

Even the machines are asleep now. The city seems far away. But there is still a shimmer of light in the deserted streets I pass through. Now and then scattered fireworks etch trails of light across the blue-black sky and explode. The distant boom takes a moment to reach me. It's New Year's Eve.

There are no streetlights. The cranes are silent silhouettes against the lighter sky. Everything is closed, ciimmed, resigned.

Svajer Wharf is a white surface in the dark. The new snow on the ice gathers the scant light in the air and gleams dully. Only a solitary car has been here before me, and I walk in its tracks.

The sign on the post is still covered with plastic. With the little rip I left behind. The dock, the gangway, and part of the deck have been cleared of snow. A few crates have been moved to make room for a pallet of red barrels. Aside from the snow and the barrels and the darkness, everything is the same as yesterday.

There is no light on board.

On my way up the gangway I start thinking about the car tracks. In snow, tire tread makes a slight backward slide inside the track itself. The track I had followed went down to the harbor. There was no return track. There are no other roads to or from Svajer Wharf than the one I came along. But the car is nowhere to be seen.

The lacquered door is shut but not locked. Inside, there is a faint light.

I know that the fiberglass Inuit will be there. The light is coming from somewhere behind the screen.

A little reading lamp is on the desk. Behind the desk sits professor and museum curator Andreas Licht with his head cocked, smiling at me broadly.

When I walk around the desk, the smile does not leave his face.

He is gripping the seat of his chair with both hands. As if to hold himself upright.

Close up I can see that his lips are pulled back from his teeth in a grimace. And he isn't gripping the chair. His hands are bound with thin cords of copper wire. I touch him. He's warm. I put my fingers on his neck. There's no pulse. He has no heartbeat, either. At least none that I can feel.

He has cotton in the ear facing me. Like a small child with an inner-ear infection. I walk around him. He has cotton in the other one, too.

I am no longer curious. Now I want to go home.

At that moment the hatch door over the stairs is shut. There is no warning, no sound of footsteps. It is simply closed, quietly and calmly. Then it is locked from the outside.

Then the light goes out.

Only now do I realize why there was so little light in the room. Blind people have no need for light. It's absurd to think about that now, but that's my first thought in the dark.

I get down on my knees and crawl under the desk. That may not be a good idea. That may be the ostrich's strategy. But I have no desire to stand there towering in the darkness. Down on the floor I can feel the curator's ankles. They are warm, too. And they are also bound to the chair with wire.

There's a movement on the deck above my head. Something being dragged. I fumble around in the dark and get hold of a telephone cord. I follow it and suddenly wind up with the end in my hands. It has been ripped out of the jack.

Then the ship's engine starts up, a big diesel engine's slow awakening. It remains idling.

I run out into the darkness. Twenty-four hours ago I oriented myself to the room. So I know where there's a door. I reach the bulkhead right next to it. It's not locked. As I step through, the engine noise grows louder.

The room has small portholes high up and facing the dock. A faint light shines through them. This room explains how the curator solved his commuting problem: He lived on board. It was furnished as a bedroom for him. A bed, a nightstand, a built-in wardrobe.

The engine room must be behind the far wall. It's insulated, but there is still a distinct thudding. When I try to look out the porthole, the noise becomes a roar. The ship slowly swings away from the dock. The engine has been put into gear. There's not a soul in sight. Only the black contour of the disappearing wharf.

There's a spark on the dock. Only a glint of light, like someone lighting a cigarette. The glow rises and floats in an arc toward me. Trailing a dripping tail of embers after it. It's a firecracker.

It explodes not far above my head with a muted bang. The next instant I am blind. A vicious white flash flings itself at me from the wharf and the water. At the same moment the fire sucks all the oxygen out of the air, and I throw myself to the floor. It feels as if I have sand in my eyes, as if I'm breathing in a plastic bag that someone is blowing on with a hair dryer. It's the barrels of gasoline, of course. They poured gasoline over the ship.

I crawl over and open the door to the room I came from. Now there is all the light you could ask for. The covering over the skylights has burned away, and the room is illuminated by what seems like a gigantic sun lamp.

On the deck there is a series of muffled explosions, and the light outside flickers blue and then yellow. Then the air is filled with burning epoxy paint.

I creep back to the bedroom. It's as hot as a sauna. Against the whiteness of the portholes I can see the smoke that has started to seep inside. The fire vanishes from one of the panes for a moment. The silo of the soybean factory lights up as if it's sunset, the windows along Iceland Wharf glow like molten glass. It's the reflection from the fire all around me.

Then a web of cracks spreads across the glass and the view vanishes.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Рута Шепетис - Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray]](/books/414915/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between-shades-thumb.webp)