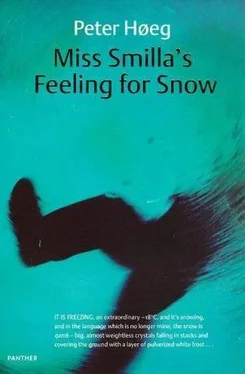

Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Høeg - Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I can see that you're a fine connoisseur of women, Verlaine. What else were you doing in Chiang Rai?" He's not unaffected by the compliment. That's why he answers the question. "I'm a lab technician. We were making heroin. At the time the woman arrived, they had sent the army after us, from all three countries. So Khum Na went on TV and said, `Last year we put 900 tons on the market, this year we'll ship 1,300, and next year 2,000 tons, unless you call your soldiers home.' The day he made that announcement, the war was over."

I'm on my way out the door when he speaks again. "Human beings ate the parasites. The worm is an instrument of the gods. Like the poppy."

3

Tørk is waiting for me. When we reach the bottom, we've descended about sixty-five feet. The tunnel, which now runs horizontally, has a rough, rectangular concrete reinforcement. It ends in black emptiness. Tørk goes first. We stop in front of an abyss.

At our feet there's a drop of eighty feet to the floor of the cave. Stalagmites of ice stretch up toward us from the ground, glistening, rainbow-colored.

Tørk breaks off a piece of ice and tosses it into space. The abyss is transformed into a series of rings and then fog; then it ceases to exist. We've been looking at the ceiling of the cave reflected in a lake right at our feet; water so still that it could never exist above ground. Even now, as it's traversed by ripples, my eyes refuse to believe that it's water. Calm slowly returns, and the underground world is reestablished.

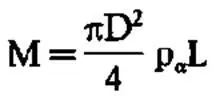

The growth patterns of stalactites and descriptions of their crystal formations were outlined by Hatakeyama and Nemoto in Geophysical Magazine, no. 28, 1958. By Knight in the Journal of Crystal Growth, no. 49, 1980. And by Maeno and Takahashi in their article "Studies on Icicles," in Low Temperature Science, vol. A, no. 43, 1984. But the most viable configuration to date was proposed by myself and Lasse Makkonen at the Laboratory of Structural Engineering in Espoo, Finland. It demonstrates that a stalactite grows like a reed, a hollow tube of ice that closes around water in its liquid state. That the mass of the stalactite can be simply expressed as:

where D is the diameter, L is the length, OQ is the density of the ice, and Tr in the numerator of the fraction is, of course, a result of the fact that we are calculating based on a hemispheric drop with a diameter set at 4.9 mm.

We proposed our formula out of fear of the ice. At a time when there had been a series of accidents in Japan with stalactites falling from the roofs of railroad tunnels and boring right through train cars. Here, above our heads, there are more stalactites and larger ones than I've ever seen in my life. Instinctively I want to move away, but I can sense Tørk next to me and give up the attempt.

The room is a cathedral. Overhead, the ceiling forms a vault at least fifty feet high, reaching almost to the surface of the glacier. All around the dome there are fractured areas where pieces have broken off and fallen, and where the ice has covered the floor, filled the grotto, and then melted again.

During periods when Moritz was gone and we couldn't afford kerosene, or when supplies were short because the ship hadn't arrived, my mother would set paraffin candles on top of a mirror. Even with only a few candles, the effect of their reflections would be overwhelming. It's the same way with Tørk's miner's lamp. He holds it steady to give me time, and the light is seized by the ice, magnified, and thrown into the air like beams raining upward.

The long spears of ice seem to be floating. Gleaming with prisms, they drip down from the ceiling, stretching toward the earth. There could be ten thousand or even more. Some of them are intertwined, like chains of cascading Gothic cathedrals; others are small and densely packed-pincushions of quartz.

Beneath them is the lake. Maybe a hundred feet across. In the middle lies the stone. Black and motionless. The water surrounding it is slightly milky with bubbles dissolving in the glacier ice. The room has no odor except for the light sting of ice in my throat. The only sounds are drops falling at long intervals. The ceiling is such a distance from the stone that an equilibrium has been established. Very little freezes or melts in this room. Water circulation is minimal. The place is lifeless.

If it hadn't been for the heat, that is. It's exactly like the heat in the igloos of my childhood. The cold radiating from the walls makes the heat seem inviting. Even though the temperature is between 32° and 41°F.

A pile of gear is lying near us. Air tanks, coveralls, flippers, harpoons, and a crate' containing plastic explosives. Ropes, flashlights, hand tools. No one is here except us. The ice creaks once, as if someone were moving a heavy piece of furniture in an adjoining room. But there are no adjoining rooms. There is only compact ice.

"How will you get it out?" I ask.

"We'll blast a tunnel," he says.

That's possible. It will have to be about a hundred yards long. But they won't have to reinforce it. And the stone will roll through the tunnel by itself, if it has the proper slant. Seidenfaden could take care of that. Katja Claussen will force him to do it. And Tørk will force her, and the mechanic. This is how I've experienced the world ever since I left Greenland. As a chain of force.

"Is it alive?" he asks quietly.

I shake my head. But that's because I don't want to believe it is. He cups his hands around the miner's lamp. Its beam is now directed at the snow beneath us. From there it's reflected upward. In this way the individual stalactites are obscured but a cloud of hovering reflections is visible, like gemstones defying gravity.

"What happens if the worm gets out?" I ask.

"We'll keep the stone enclosed."

"You can't hold on to the worm. It's microscopic."

He doesn't reply.

"You can't know," I say. "No one knows. You only know what you've learned from a few laboratory experiments. But there's a small chance that it's a real killer." He doesn't reply.

"What was the other answer to my question about why the worm hasn't already spread?"

"As a child I spent a year in Greenland, on the west coast. There I collected fossils. Since then I've occasionally toyed with the idea that the extermination of various species in prehistoric times might have been caused by a parasite. Who knows-maybe it was the Arctic worm. It would have had the necessary characteristics. Maybe it was the worm that eradicated the dinosaurs."

His voice has a teasing undertone. Suddenly I understand him.

"But that's not important, is it?"

"No, it's not important." He looks at me. "The true reality of things is not important. What's important is what people believe. They will believe in this stone. Have you ever heard of Ilya Prigogine? A Belgian chemist who received the Nobel Prize in '77 for his description of dissipative structures. He and his students have been working nonstop. on the idea that life originated from inorganic substances that were irradiated with energy. These ideas have paved the way. People are waiting for this stone. Their belief and anticipation will make it real. They will make it alive regardless of the true nature of the stone."

"And the parasite?" I ask.

"I can already hear the first ranks of speculative journalists. They'll write that the Arctic worm represents a significant stage in the encounter between the stone, inorganic life, and higher organisms. They'll come to all sorts of conclusions, none of which is important. What's important are the forces of fear and hope that will be let loose."

"Why, Tørk? What do you get out of it?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Smilla's Sense of Snow aka Miss Smilla's Feeling for Snow» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Рута Шепетис - Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray]](/books/414915/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between-shades-thumb.webp)