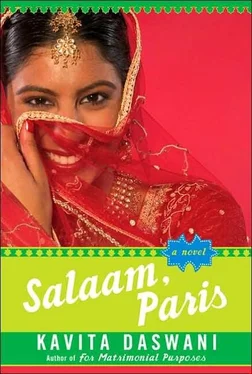

Only, as was the way things were done back then, Hassan Bhatt never saw my mother until the wedding ceremony was about to begin. He had never thought to assume that she would be anything less than stunning, because no woman in my family ever had been. He admitted later that he might have heard someone comment, as the engagement was being announced, that my mother was “not quite as lovely as the other sisters, but not bad.” For Hassan Bhatt, “not bad” was good enough, and surely would still be divine. Perhaps he should have been tipped off by my mother’s name. Where her sisters were given appellations that spoke of loveliness, my mother had been christened Ayesha-named after the wife of the prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam. It was a noble name, no doubt. But Hassan Bhatt, as it turned out, was not in the least bit interested in nobility.

Aunt Sohalia told me years later of the look that appeared on Hassan Bhatt’s face when the red chiffon bridal scarf that covered my mother’s head was first lifted. She described the look as one of “severe disappointment,” but nobody said a word, not even the bridegroom. And in my grandfather’s mind, there wasn’t even an inkling of a notion that this sudden and rather unseemly revelation should be an impediment to my mother’s marital happiness, given that, after all, Hassan Bhatt was far too decent a man, and from far too upstanding a family, to abandon a marriage simply because he didn’t like the way his wife looked.

For one of the few times in his life, Nana was wrong.

There had been a honeymoon planned, in Ooty, a snow-capped vacation resort in India, but that had been abruptly cancelled when Hassan Bhatt announced that he had some pressing business to take care of in Lahore. Although he tried to convince my mother otherwise, she went with him, assuming that the rest of her life would be spent by his side, being his wife.

Two months later, she was back in Mahim, at her father’s house, with me in her belly, no larger than a grain of rice.

Nineteen years later, my mother had yet to recover from the humiliation of being left by a husband because of the way she looked-or didn’t. I would catch her occasionally looking at their wedding photograph, a bland black-and-white shot framed in gold that she kept in the bottom drawer of a chest in our bedroom. I had often snuck in there to look at it myself, to gaze at the wide-eyed nervousness on my mother’s face and the momentous sadness on that of Hassan Bhatt’s, my nana standing cautiously behind them.

Soon after Zoe had left for work one morning, just as I was about to wring out the laundry and hang it up to dry in the small, square-shaped bathroom, Shazia arrived. She smiled broadly, as if I had just seen her yesterday, as if I was neither homeless nor penniless nor jobless in a still-strange city.

“How are you doing?” she asked, throwing her arms around me.

“OK,” I replied. “How’s your mother feeling?”

“Better, actually. I think me being here has really helped. We’ve been spending lots of time at home these past couple of weeks, just her and I. It’s been good. I’ve promised her I’ll come back as soon as a let-up in my work schedule allows it. I’m flying back to L.A. tomorrow.

“What about you?” she asked, finally turning her attention back to me again.

I had started to resent Shazia for encouraging me to do something as foolhardy as this, and it finally began to show. And now, she was returning to Los Angeles, leaving me behind.

“What am I doing?” I said to her, turning back toward the living room while she slipped off her coat and followed me. “This was a stupid idea, and I should never have allowed you to talk me into it. But I have nobody to blame but myself. I want to go home, but Nana won’t take me back, I’m sure of it. Once he says these things, he never changes his mind.”

“Oh, stop feeling sorry for yourself,” Shazia said, her voice laced with recrimination, her face utterly lacking in sympathy. “You’re not a kid anymore. And it’s only been a couple of weeks. You’ll be fine, honest. You’ll be better than fine. We all have problems. I was supposed to marry a boy from Karachi, but he rejected me flat-out. Said I was too fat. I promised myself I would never put myself through that humiliation again.”

“I didn’t know,” I said softly. “You never mentioned.”

“Well, it’s not something I like to talk about,” Shazia said, the bitterness in her face now yielding. “It just made me really resent our culture, you know? There’s a lot about it that sucks.”

“I’m sorry you feel that way, but I’m still proud of where I come from,” I said, aware that I was sounding naïve. “I can’t imagine never returning to India.”

“Nobody’s saying that,” she said. “But it’s OK to develop an affinity with another land, another culture. It doesn’t make you any less Muslim. I’m Muslim, but I’m American as well. I can’t tell you who the Pakistani prime minister is, but I know the name of Kate Hudson’s baby.” She laughed.

She pulled me down onto the couch and took a sheet of yellow lined paper out of her bag.

“Look, good news,” she said. “A job, a permanent place to live, how to get your visa extended… Everything you need. You start next week.”

I glanced down and saw a scribbled name of a café with an address and phone number. Below that were other addresses, other numbers. My entire new life, according to Shazia, whittled down into a few scrawled lines.

“A good friend of mine owns a cute café, very trendy, in Odéon. He needs a cashier, which I thought would be perfect for you because you don’t really have to speak. His English is great, so at least you can communicate. It’s a cash job-he pretty much only hires illegals,” said Shazia, lowering her voice although we were alone. “The pay isn’t bad, and it’s enough to share a place I found with a few other girls. Those are the details there,” she said, pointing to the second address. “You can walk to work, and all the girls keep strange hours, so you’ll have the place to yourself a lot. It’s perfect,” she said, folding her hands on her lap, a look of smug satisfaction on her face.

“I’m glad you think so,” I said, the resentment returning. “I don’t want any of it. I want to go home.”

Shazia’s face softened, and she put her hand on top of mine. “Listen, all those dreams you came here with, you still have to achieve them,” she said. “You haven’t had your Sabrina moment yet, have you?”

I shook my head, disconsolate, but now feeling embarrassed by my delusion.

“You can’t leave here until you feel what you said you wanted to feel,” Shazia said. “Not until you can show everyone you are no longer just the pretty Shah girl from Mahim.”

I nodded, carefully folded up the sheet of paper, and rose to bid my distant cousin a final good-bye.

My brown suitcase sat behind me in the cashier’s booth, waiting to be taken to its new home. It still bore half-peeled-off stickers from my grandfather’s travels-a dozen or so faded Air India tags dotted over its surface, the familiar yellow-and-red Maharajah now grimy with age.

Another bill was brought to me, a shiny credit card placed upon it, and I swiped it through the small machine on my right, punched in a code, ripped out the resulting printout, and placed it back on the tray for the waiter to return to his customer. I had been doing this for five hours and twenty minutes, off and on, and when it was slow I leafed through the English-French dictionary that Shazia had given me before she left.

Читать дальше