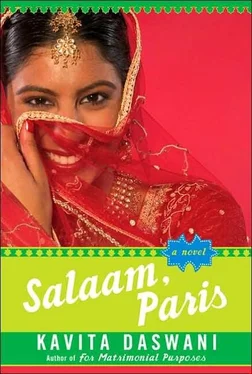

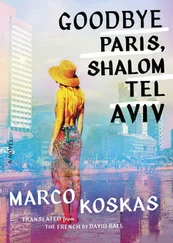

Kavita Daswani

Salaam Paris

© 2006

In memory of my dearest grandfather,

Dialdas Verhomal Daswani, with whose

blessings all things are possible.

My sincerest thanks to Aimee Taub, my editor at Plume, for always being so gracious and for having such tremendous instincts about the characters on a page and the world they inhabit.

And to Jodie Rhodes, who is tenacious and smart and kind-everything an agent should be.

And to everyone at Penguin, for their faith in me.

Given that I have never so much as exposed my arms in public, and that until just a few minutes ago I had been concealed, cosseted, and cloistered for most of my nineteen years, I should be leaping out of my chair and running for my life.

But I am too stunned to move.

I am behind a dressing screen, in a back room at a nightclub in Paris, a nude thong barely covering the area that only my future husband is ever meant to see. Apart from that, and two small, circular Band-Aid-type things that have been stuck onto my nipples, and which I am later told are called “pasties,” I am naked. The other girls around me, all either blond-haired or black-skinned, are smoking cigarettes and sucking from miniature bottles of champagne. A hairstylist has backcombed my long black hair with such ferocity that I fear I will never get the knots out. Someone else has applied dark purple lipstick to my mouth and slathered pale white foundation on my face, making me look like I am in dire need of a blood transfusion.

I am alone in Paris, almost nude, looking like a corpse, surrounded by smoking, drinking sinners.

I am a Muslim girl, culturally more accustomed to a black veiled burka than this wisp of a panty that is lodged in my backside.

If my elders were here, they would surely impose a fatwa on my head. It happened to Salman Rushdie, I remind myself, for a lot less.

Someone tugs a skinny sweater over my head, instructing me to purse my lips to prevent the purple from staining the white knit. Despite the pasties, my nipples poke through the thin fabric. Someone else squeezes me into a pair of pink leather hot pants. Sparkling high-heeled sandals are thrust onto my hurriedly varnished feet. A wooly coat is thrown on me; a poodle that has been dyed pink is shoved under my arm.

On the other side of the screen, I hear loud, throbbing music. I am pushed toward a short hallway, someone barking in my ear, “Allez! Allez!” Staring straight ahead, I see only white-bright lights up high, strange faces reflected in the dark.

I teeter toward them. The poodle pees in my hand.

I hear clapping, whistling, and deafening music.

This is my moment.

If there had ever been such a thing as a Miss Muslim contest, all but one of the women in my family would have won it.

My great-grandmother was named Sundari-which means, simply, “beautiful” in Hindi. Her daughter, my grandmother, was blessed with the moniker Abha, which translates even more vividly into “lustrous beauty.” One aunt is Gaura-“fair-skinned” and another Sohalia-“moon river”-to describe the luminescence of her face. They were the beauties of their eras, each one sought out by a man who was prominent and powerful enough to win their hearts.

All of them, except my mother.

Had a Miss Muslim contest ever existed, the beauty-pageant baton that would have been passed on from generation to generation would have stopped at her. Which is why when I was born, Parvez, the midwife who had delivered me at our home in the Mumbai suburb of Mahim, went running through the streets of our neighborhood, joyous and jubilant.

“He has listened!” Parvez yelled out to all. “Allah has visited his blessings on the Shah family once more! This child is most divine!”

They decided to name me Tanaya-which means “child of mine”-and the choice of which came as a great surprise to our relatives. After all, most of the women in my family had been graced with names that signified good looks. And here was I, signifying nothing but ownership.

“Evil eye,” my grandfather muttered when my aunt Gaura wondered out loud why I couldn’t be named something more symbolic. “Yes, she is fair and dimpled and sweet. But we have been cursed before.”

My mother, I was told, sobbed and turned her eyes away as I tried to suckle on her breast. But she instead handed me over to Gaura who had borne a son just eleven days earlier, and who would breastfeed me instead of my own mother.

As a young girl, I had no concept of being attractive. When I looked in the mirror, I saw only a girl who had few friends, a strict grandfather, a grandmother I had loved dearly but who had died when I was not quite seven, a mother who seemed sad most of the time, and a father I had never known.

It wasn’t until I was thirteen that I began to notice that I looked a little different compared to other girls my age. I was taller than everyone else in my class; and even without the benefit of braces, regular skin-whitening treatments, or eyebrow threading sessions, none of which my grandfather-my nana-would ever agree to pay for, people always stared at me, men sometimes longingly. Around then, my nana stopped putting his arm around me as we watched TV on the couch or holding my hand when we went out to buy sticky pink candy from the street vendors or helping me brush my hair at night. When I turned thirteen and my breasts started to blossom and hair appeared in the unlikeliest places, I stopped being my nana’s little girl.

It was at about this time that the first sign of my hereditary signature began to appear. All the women in my family, with the exception of my mother, were known for their “Shah streak,” a swath of silver-gray across the hairline. It looked like the stripe on a raccoon’s tail, a brush of moonlight against a dark night sky. It was, singularly, what had defined almost all of my maternal ancestors-a quirk of nature that graced us virtually without exception, leaving only my mother out. On me, it sprouted tentatively initially, then bloomed. When the first strand came, my aunt Gaura kissed me on the cheek, telling me that in our family, it was considered a mother’s blessing, and the more it grew, the more munificent the maternal goodwill. Being that as it may, I had hoped, somewhat naively, that with the appearance of the streak my mother might finally love me a little more.

As my Shah streak grew in and my breasts developed and my stature altered, I was, at fifteen, now as tall and slender as my aunts. My grandfather forbade me from using the public bus to go back and forth from school, knowing about the body-grazing and flesh-pinching that most of the women aboard had to submit to. Whenever he could, he would come by auto-rickshaw to drop and fetch me, rarely letting me out of his sight.

“You are a young woman now,” he said to me when I was sixteen. “You have nothing else to offer except the face that Allah has blessed you with. Men of poor moral standing will start to think things when they see you. I believe it is time to settle your mind on the only role you have in this world: a pretty and quiet wife and a devoted mother. Remember that, and you will always be happy.”

And I had had no reason not to believe him.

Every teenage girl has a turning point, a time when she realizes that she is more than just the sum of the expectations of her. I finally reached that point two days shy of my nineteenth birthday.

Читать дальше