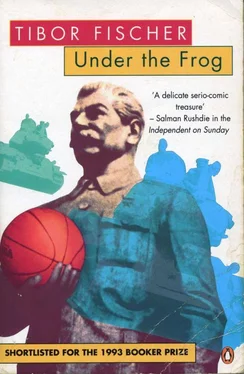

Tibor Fischer - Under the Frog

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tibor Fischer - Under the Frog» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Under the Frog

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Under the Frog: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Under the Frog»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Shortlisted for Booker Prize 1993

Set in post-war Hungary between 1944 and 1956, this ferociously funny and bitterly sad story follows the fortunes of two young men in the pursuit of sex and the avoidance of work and army service. They survive the chaos of communism by becoming part of a travelling basketball team.

Under the Frog — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Under the Frog», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What Csokonai was doing was extremely dangerous and Gyuri had no intention of frequenting him any longer than was necessary to obtain an apple or two. The other week, a worker who had either too much pálinka or hardship had suddenly burst out with: ‘They say that under Horthy, Hungary was the land of two million beggars. Well at least under Horthy it was just the beggars who were beggars and not the whole sodding country. I can’t feed my family on this.’ A black car had been waiting for him outside the gates. ‘We have a few questions. It’ll only take five minutes.’ No one had seen him since, but then no one had ever seen again those people whom the Russians had invited for ‘malenky robot,’ a little work five years ago.

Being an old-world courtesy fiend, Csokonai handed over three apples which Gyuri could only bring himself to refuse once. Mulling over how egg-shell thin dignity was when your belly was yelling, Gyuri returned to work to find Sulyok talking to Tamás: ‘Listen, Tamás, we need a little favour, we’re having some comradely difficulties.’ It took Sulyok some time to spit it out, but the problem was this: there was only one place manufacturing the machine tools Ganz needed and for some reason – enmity, superior bribery, incompetence, kinship, the machine tools were being shipped to other factories, not to where they were needed at Ganz, where despite Stakhanovite book-cooking, the Three Year Plan was not being fulfilled. ‘Tamás, could you go over there and explain in a constructive, fraternal and socialist manner the absolute dire necessity for some urgent supplies to aid the intensification of the Three Year Plan fulfilment situation?’

‘You want me to hijack one of their deliveries, right?’ asked Tamás.

Taken aback by this uncomradely language, Sulyok winced, but didn’t blab anymore. ‘Yes,’ he said, handing over a set of lorry keys. ‘Take Gyuri and some of the other lads if you need.’ It’s all about having the right skills for the right task, Gyuri thought. You can read Lenin on International Law, but no amount of reading Lenin on ambushing and highway robbery could help you if you didn’t know the business.

Tamás picked up Palinkas, another well-known pugilist, and an apprentice jaw-breaker, Bod. As they were pulling out by the front gates, Gyuri noticed Pataki, apprehended by two security men who were unwinding a long length of copper wire from underneath his shirt. Smiling, Gyuri waved, looking forward with keen anticipation to hearing how Pataki could talk his way out of that one.

Tamás dropped everyone off, one by one, wherever they wanted to go, before putting his foot down on the accelerator to head off to the Zuglo where the machine tool factory was located. ‘Don’t worry, I can take care of it on my own,’ he said to Gyuri with an expectant grin on his face, slipping his knife in between his teeth.

At home, Gyuri found Elek still parked in his armchair, but entertaining Szocs, his former doorman who came monthly to pay his respects. Szocs was the only one of Elek’s old staff who made the effort to seek him out and he was made welcome because of that and also, more saliently, because he always brought a package of food from his farming cousins. His mother had always complained that Elek showered his staff with holidays and bonuses, though as Gyuri recalled, Szocs, who had been on duty outside Elek’s office, had never copped any of the goodies.

Szocs was inescapably stuck in cheerfulness but went up a jubilation or two when he saw a younger Fischer. ‘How are you, Gyuri? Settling down yet? Thinking about getting married?’ Gyuri knew he was at the age when everyone was immensely inquisitive as to what he was doing with his willy, so he was prepared for this sort of inquiry from his seniors; he was as keen to be castrated as to get married but he laughingly denied major romance with good grace. Someone who had come halfway across Budapest to deliver food was entitled to question away. Gyuri discerned an opened package of goose crackling, and started to make arrangements digestively.

Looking down the finger he was pointing at Gyuri as if down the barrel of a gun, Szocs remarked: ‘You’ll know when you find the right one, you’ll know.’ Gyuri nodded concurringly as one does towards someone who has mustered goose crackling. ‘I knew the moment I saw my wife,’ he said chuckling. This surprised Gyuri because he had only seen Mrs Szocs once, and his first, last and lasting impression was of consummate ugliness; he had always imagined that Szocs married her out of charity, or that their wedlock was a further symptom of Szocs’s chronic misfortune rather than elective affinities. Szocs’s life was one of round-the-clock calamity: an orphan, he had been shipwrecked as a cabin-boy, lost the use of one eye from an infection, lost his toes from frostbite in a Russian prisoner of war camp, lost both his children in the great dysentery epidemic of 1919. You just had to laugh. There was surely more disaster in his past, but unusually for a Hungarian with such promising material to draw on, Szocs was very niggardly in passing out the details of his years.

‘The Party secretary catches Kovacs,’ said Szocs changing tack. ‘“Comrade Kovacs, why weren’t you at the last Party meeting?” “The last Party meeting?” replies Kovacs. “If I’d known it was the last Party meeting, I’d have brought the whole family.’” Szocs was now, in an odd way, a successful figure, now that poverty and misery had been generally distributed; he was a tycoon of jollity. In the land of the blind, Gyuri thought, the man who knows how to use the white stick is king.

The only irritating aspect to Szocs was that his whistling in totalitarianism rather invalidated one’s licence for self-pity.

Gyuri could never enjoy his resentment for quite a while after Szocs had left. Szocs’s presence made him lose that acute sense of accumulated injustice and aggrievedness that he had been so carefully working on. Elek, for example, might be sitting comfortably in the back of adversity’s big black car, but Szocs seemed to thrive on hardship like a slap up meal.

To his shame, Gyuri was glad when Szocs left and he didn’t have to pretend any more that he didn’t want to throw himself on the goose crackling. Elek had ventured out earlier to get some fresh bread and this in combination with the goose crackling yielded a profound sense of well-being, an undispersable glow of plenitude that would linger on for the minimum of an evening or until Gyuri went to do some training.

The two packets of cigarettes (French) had been part of a great plan Gyuri had been hatching to do some profitable bartering- but Elek looked so deformed, so unnatural without a cigarette that Gyuri handed them over and watched Elek’s face become an amalgam of joy and reflection on how to apportion the cigarettes chronologically

One strove to be hard, to be tough, dangerous and independent (Gyuri weighed up the effects of the pile of goose crackling) but self-discipline is such a delicate thing, a plant that wilts on either side of a narrow temperature band. In mitigation, it had been exceptionally adipose, unquestionably hastened to the capital that morning, wrapped before darkness had been dispelled, possessed of an evanescent crispness and a tang that had to be captured by taste buds within twelve hours or it would abscond to the limbo of fabulous flavour.

The glut of cigarettes and goose crackling engendered a pliancy and a conversation between the two of them. Of late, Pataki had been the top recipient of Elek’s locutions, a hunched, cigaretted dialogue running through Elek’s lewd 4material. Gyuri made a point of ostentatiously going for a run or loudly doing some housework while they were thus engaged, but it didn’t have any dampening effect.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Under the Frog»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Under the Frog» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Under the Frog» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.