“So when you do you think you’ll be moving over to Robert Taylor?” I asked.

“Not sure,” he said absentmindedly, staring out at the panhandlers who worked the gas station near my apartment.

“Well, I’m sure you’ll be busy now-I mean, even busier than you’ve been. So listen, I just wanted to thank you-”

“Nigger, are we breaking up?” J.T. started laughing.

“No! I’m just trying to-”

“Listen, my man, I know you have to write a term paper-and what are you going to write it on? On me, right?” He giggled and stuck a cigar in his mouth.

It seemed that J.T. craved the attention. It seemed that I was more than just entertainment for him: I was someone who might take him seriously. I hadn’t thought about the drawbacks of having my research dependent on the whims of one person. But now I turned giddy at the prospect of continuing our conversations. “That’s right,” I said. “ ‘The Life and Times of John Henry Torrance.’ What do you think?”

“I like it, I like it.” He paused. “Okay, get the fuck out, gotta run.”

He offered his hand as I opened the car door. I shook it and nodded at him.

My short walk north to the Lake Park projects would now be replaced by a longer commute, usually by bus, to the Robert Taylor Homes. But as a result of his relocation, J.T. reported that he’d be out of touch for a few weeks. I decided to use that time to do some research on housing projects in general and the Robert Taylor Homes in particular.

I learned that the Chicago Housing Authority had built the project between 1958 and 1962, naming it after the agency’s first African-American chairman. It was the size of a small city, with forty-four hundred apartments housing about thirty thousand people. Poor blacks had arrived in Chicago en masse from the South during the great migrations of the 1930s and 1940s, which left a pressing need for the city to accommodate them.

In the beginning, the project was greeted with considerable optimism, but it soon soured. Black activists were angry that Chicago politicians put the project squarely in the middle of an already crowded black ghetto, thereby sparing the city’s white ethnic neighborhoods. Urban planners complained that the twenty-eight buildings occupied only 7 percent of the ninety-six-acre plot, leaving huge swaths of vacant land that isolated the project from the wider community. Architects declared the buildings unwelcoming and practically uninhabitable from the outset, even though the design was based upon celebrated French urban-planning principles.

And, most remarkably, law-enforcement officials deemed Robert Taylor too dangerous to patrol. The police were unwilling to provide protection until tenants curbed their criminality-and stopped hurling bottles or shooting guns out the windows whenever the police showed up.

In newspaper headlines, Robert Taylor was variously called “Congo Hilton,” “Hellhole,” and “Fatherless World”-and this was when it was still relatively new. By the end of the 1970s, it had gotten worse. As the more stable working families took advantage of civil-rights victories by moving into previously segregated areas of Chicago, the people left behind lived almost uniformly below the poverty line. A staggering 90 percent of the adults in Robert Taylor reported welfare-cash disbursements, food stamps, and Medicaid- as their sole form of support, and even into the 1990s that percentage would never get lower. There were just two social-service centers for nearly twenty thousand children. The buildings themselves began to fall apart, with at least a half dozen deaths caused by plunging elevators.

By the time I got to Chicago, at the tail end of the 1980s, Robert Taylor was habitually referred to as the hub of Chicago’s “gang and drug problem.” That was the phrase always invoked by the city’s media, police, and academic researchers. They weren’t wrong. The poorest parts of the city were controlled largely by street gangs like the Black Kings, which made their money not only dealing drugs but also by extortion, gambling, prostitution, selling stolen property, and countless other schemes. It was outlaw capitalism, and it ran hot, netting small fortunes for the bosses of the various gangs. In the newspapers, gang leaders were commonly reported as having multimillion-dollar fortunes. This may have been an exaggeration, but it was true that some police busts of the leaders’ homes netted hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash.

For the rest of the community, the payout of this outlaw economy-drug addiction and public violence-was considerably less appealing. Combine this menace with decades of government neglect, and what you found in the Robert Taylor Homes were thousands of families struggling to survive. It was the epitome of an “underclass” urban neighborhood, with the poor living hard and virtually separate lives from the mainstream.

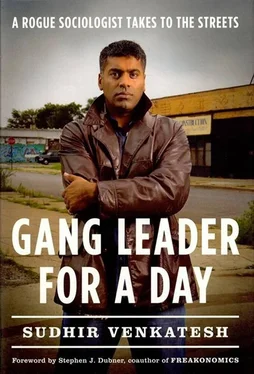

But there was surprisingly little reportage on the American inner city-and even less on how the gangs managed to control such a sprawling enterprise, or how a neighborhood like Robert Taylor managed to cope with these outlaw capitalists. Thanks to my chance meeting with J.T. and his willingness to let me tag along with him, I felt as if I stood on the threshold of this world in a way that might really change the public’s-if not the academy’s- understanding.

I wanted to bring J.T. to Bill Wilson’s attention, but I didn’t know how. I was already working on some of Wilson’s projects, but these were large, survey-based studies that queried several thousand people at a time. Wilson’s research team included sociologists, economists, psychologists, and a dozen graduate students glued to their computers, trying to find hidden patterns in the survey data that might reveal the causes of poverty. I didn’t know anyone who was walking around talking to people, let alone gang members, in the ghetto. Even though I knew that my entrée into J.T.’s life was the stuff of sociology, as old as the field itself, it still felt like I was doing something unconventional, bordering on rogue behavior.

So while I devoted time to hanging out with J.T., I told Wilson and others only the barest details of my fieldwork. I figured that I’d eventually come up with a concrete research topic that involved J.T., at which point I could share with Wilson a well-worked-out set of ideas.

In late spring, several weeks after his meeting with Curly, J.T. finally summoned me to Robert Taylor. He had moved in with his mother in her apartment, a four-bedroom unit in the northern end of the complex. J.T. usually stayed in a different neighborhood, in one of the apartments he rented for various girlfriends. But now, he said, he needed to be in Robert Taylor full-time to get his gang firmly transplanted into its new territory. He told me to take the bus from Hyde Park down Fifty-fifth Street to State Street, where he’d have a few gang members meet me at the bus stop. It wasn’t safe to walk around by myself.

Three of J.T.’s foot soldiers picked me up in a rusty Caprice. They were young and affectless and didn’t have anything to say to me. As low-ranking members of the gang, they spent a lot of their time running errands for J.T. Once, when J.T. was a little drunk and getting excited about my writing his biography, he offered to assign me one of his gang members as a personal driver. I declined.

We drove up State Street, past a long stretch of Robert Taylor high-rises, and stopped at a small park in the middle of the complex. It was the sort of beautiful spring day, sunny, with a fresh lake breeze, that Chicagoans know will disappear once the brutal summer settles in. About fifty people of all ages were having a barbecue. There were colorful balloons printed with HAPPY BIRTHDAY CARLA tied to picnic tables. J.T. sat at one table, surrounded by families with lots of young children, playing and eating and making happy noise.

Читать дальше