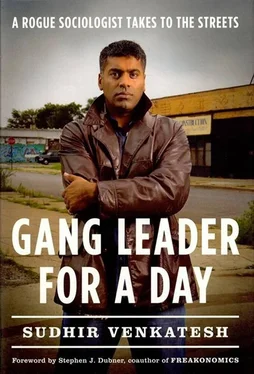

This explanation didn’t satisfy me, and I wanted to talk to J.T. about it. But he was so busy these days that I barely saw him-and when I did, he was usually with other gang leaders, working on the political initiatives that the BKs were putting together.

And then, just before Labor Day, J.T.’s efforts to impress his superiors started to bear fruit. He told me that he was heading south for a few days. The highest-ranking BK leaders met downstate every few months, and J.T. had been invited to his first big meeting.

The Black Kings were a large regional gang, with factions as far north as Milwaukee, southward to St. Louis, east to Cleveland, and west to Iowa. I was surprised when J.T. first mentioned that the gang operated in Iowa. He told me that most Chicago gangs tried to recruit local dealers there, usually by hanging out at a high-school basketball or football game. But Iowa wasn’t very profitable. Chicago gang leaders got frustrated at how “country” their Iowa counterparts were, even in places like Des Moines. They were undisciplined, they gave away too much product for free, they drank too much, and sometimes they plain forgot to go to work. But the Iowa market was large enough that most Chicago gangs, including the Black Kings, kept trying.

J.T. had made clear to me his ambition to move up in the gang’s hierarchy, and this regional meeting was clearly a step in that direction.

In his absence, he told me, I could hang out as much as I wanted around his building. He said he’d let his foot soldiers know they should be expecting me, and he left me with his usual caution: “Don’t walk too far from the building. I won’t be able to help you.”

After J.T. told me about his plans, I was both excited and nervous. I had hung around Robert Taylor without him, but usually only for a few hours at a stretch. Now I would have more time to walk around, and I hoped to meet more people who could tell me about the gang from their perspective. I knew I had to be careful with the line of questioning, but at last I’d been granted an opportunity to get out from under J.T.’s thumb and gain a wider view of the Black Kings.

I immediately ran into a problem. Because I’d been spending so much time with the Black Kings, a lot of the tenants wouldn’t speak to me except for a quick hello or a bland comment about the weather. They plainly saw me as affiliated with the BKs, and just as plainly they didn’t want to get involved with me.

Ms. Bailey, the building president, was one of the few tenants willing to talk. Her small, two-room office was located in J.T.’s building, where she lived as well. This was in the northern end of the Robert Taylor Homes, sometimes called “Robert Taylor A.” A few miles away, at the southern end of the complex, was “Taylor B,” where a different group of gangs and tenant leaders held the power. On most dimensions daily life was the same in Taylor A and Taylor B: they had similar rates of poverty and drug abuse, for instance, and similar levels of gang activity and crime.

But there was at least one big difference, Ms. Bailey told me, which was that Taylor B had a large Boys & Girls Club where hundreds of young people could shoot pool, play basketball, use the library, and participate in youth programs. Ms. Bailey was jealous that Taylor A had no such facility. Even though Taylor B was walking distance from Taylor A, gang boundaries made it hard to move freely even if you had nothing to do with a gang. It was usually teenagers who got hassled when they crossed over, but even adults could have trouble. They might get searched by a gang sentry when they tried to enter a high-rise that wasn’t their own; they might also get robbed.

The best Ms. Bailey could offer the children in Taylor A were three run-down apartments that had been converted into playrooms.

These spaces were pathetic: water dripped from the ceilings, rats and roaches ran free, the bathrooms were rancid; all these playrooms had were a few well-worn board games, some stubby crayons, and an old TV set. Even so, whenever I visited, I saw that the children played with as much enthusiasm as if they were at Disney World.

One afternoon Ms. Bailey suggested that I visit the Boys & Girls Club in Taylor B. “Maybe with your connections you could help us raise money for a club like that in our area,” she said.

I told her I’d be happy to help if I could. That Ms. Bailey saw me, a middle-class graduate student, as having “connections” said a lot about how alienated her community was from the powerful people in philanthropy and government who could actually make a difference.

Since Taylor B was controlled by the Disciples, a rival to J.T.’s Black Kings, Ms. Bailey personally walked me over to the Boys & Girls Club and introduced me to Autry Harrison, one of the club’s directors.

Autry was about thirty years old, six foot two, and thin as a rail. He wore large, round glasses too big for his face and greeted me with a big smile and a handshake. “You got any skills, young man?” he asked brightly.

“I can read and write, but that’s about it,” I said.

Autry led me into the poolroom and yelled at a dozen little kids to come over. “This young man is going to read a book to you,” he said, “and then I’d like you to talk about it with him.” He whispered to me, “Many of their parents just can’t read.”

From that day forward, Autry was happy to have me at the club. I quickly got to know him well. He had grown up in Robert Taylor, served in the army, and, like a few caring souls of his generation, returned to his neighborhood to work with young people. Recently he’d gone back to school to study criminal justice at Chicago State

University and was working part-time there as a research assistant to a professor who was studying gangs. Autry was married, with a three-year-old daughter. Because of his obligations at the club and at home, he told me, he sometimes had to drop classes and even take a leave of absence from school.

In his youth Autry had made his fair share of bad choices: he’d been a pimp and a gang member, for instance, and he had engaged in criminal activity. He’d also suffered the effects of project living- he’d been beaten up, had his money stolen, watched friends get shot and die in a gang war.

Autry sometimes sat for hours, leaning back in a chair with his skinny arms propped behind his head, telling me the lessons he’d learned from his days as a pimp. These included “Never sleep with your ladies,” “Always let them borrow money, because you got the power when they owe you shit,” and “If you do sleep with them, always, always, always wear a condom, even when you’re shaking their hand, because you just never know where they’ve been.”

We got along well, and Autry became a great source of information for me on how project residents viewed the gang. The club, it turned out, wasn’t a refuge only for children. Senior citizens played cards there, religious folks gathered for fellowship, and social workers and doctors provided free counseling and medical care. Just like many of the hustlers I’d been speaking to, Autry felt that the gang did help the community-giving away food, mediating conflicts, et cetera-but he also stressed that the community spent a lot of time “mopping up the gang’s mistakes.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“They kill, sometimes for the most stupid reasons,” he said. “ ‘You spoke to my girlfriend…’ ‘You walked down the sidewalk in my territory…’ ‘You looked at me funny- That’s it, I’ll kill you!’ ”

“So it’s not always fights about drugs?”

“Are you kidding me?” He laughed. “See, the gang always says it’s a business, and it is. But a fifteen-year-old around here is just like any fifteen-year-old. They want to be noticed. They don’t get any attention at home, so they rebel. And at the club we’re always mop-ping up their mistakes.”

Читать дальше