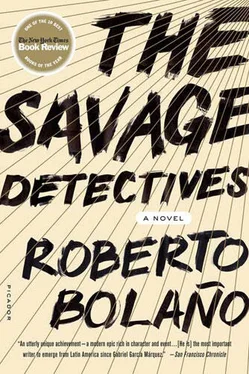

Roberto Bolaño - The Savage Detectives

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roberto Bolaño - The Savage Detectives» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на испанском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Savage Detectives

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Savage Detectives: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Savage Detectives»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Savage Detectives — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Savage Detectives», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then the Spaniards turned up, smoking a joint, and they asked Hugh and the night watchman why they were crying, and they both started to laugh, and the Spaniards, such decent, normal people, said Hugh, understood everything without having to be told and passed them the joint and then the four of them headed back together.

And how do you feel now? I asked him. I feel fine, he said, ready for the harvest to be over and to go home. And what do you think about the night watchman? I asked. I don't know, he said, that's your problem, you're the one who has to think about that.

When the work ended, a week later, I went back to England with Hugh. My original idea was to travel south again, to Barcelona, but when the harvest was over I was too tired, too ill, and I decided that the best thing would be to go back to my parents' house in London and maybe visit the doctor.

I spent two weeks at home with my parents, two empty weeks, not seeing any of my friends. The doctor said I was "physically exhausted," prescribed some vitamins, and sent me to the optician. He said I needed glasses. A little while later I moved to 25 Cowley Road, Oxford, and I wrote the night watchman several letters. I told him all about everything: how I felt, what the doctor had said, how I wore glasses now, how as soon as I had made some money I was planning to come to Barcelona to visit him, that I loved him. I must have sent six or seven letters in a relatively short period of time. Then term started, I met someone else, and I stopped thinking about him.

Alain Lebert, Bar Chez Raoul, Port-Vendres, France, December 1978. Back then I was living like I was in the Resistance. I had my cave and I read Libération in Raoul's bar. I wasn't alone. There were others like me and we hardly ever got bored. At night we talked politics and shot pool. Or we talked about the tourist season that had just ended. Each of us remembered the stupid things the others had done, the holes we'd dug ourselves into, and we laughed our heads off on the terrace of Raoul's bar, watching the sailboats or the stars, very bright stars that announced the arrival of the bad months, the months of hard work and cold. Then, drunk, we each headed off on our own, or in pairs. Me: to my cave outside of town, near the rocks of El Borrado. I have no idea why it's called that I never bothered to ask. Lately I've noticed a disturbing tendency in myself to accept things the way they are. Anyway, as I was saying, each night I'd go back alone to my cave, walking like I was already asleep, and when I got there I'd light a candle, in case I'd gotten turned around. There are more than ten caves at El Borrado and half had people in them, but I never ended up in the wrong one. Then I'd climb into my Canadian Impetuous Extraprotector sleeping bag and start to think about life, about the things you see happen right in front of you, things that sometimes you understand and other times (most of the time) you don't, and then that thought would lead to another, and that other thought would lead to one more, and then, without realizing it, I'd be asleep and flying along or crawling, whatever.

In the morning, El Borrado was like a commuter town. Especially in the summer. Every cave had people in it, sometimes four or more, and around ten o'clock everyone would start to come out, saying good morning, Juliette, good morning, Pierrot, and if you stayed in your cave, tucked away in your sleeping bag, you could hear them talking about the sea, the brightness of the sea, and then a noise like the clanking of pans, like somebody boiling water on a camp stove, and you could even hear the click of lighters and a wrinkled pack of Gauloises being passed from hand to hand, and you could hear the ah-ahs and the oh-ohs and the oh-la-las, and of course there was always some idiot talking about the weather. But over it all what you really heard was the noise of the sea, the sound of the waves breaking against the rocks of El Borrado. Then, as summer ended, the caves emptied, and there were only five of us left, then four, and then just three, the Pirate, Mahmoud, and me. And by then the Pirate and I had found work on the Isobel and the skipper told us we could bring our gear and move into the crew's quarters. It was nice of him to offer, but we didn't want to take him up on it right away, since we had privacy in the caves and our own space, while belowdecks it was like sleeping in a coffin and the Pirate and I had gotten used to the comforts of sleeping in the open air.

In the middle of September we started to go out on the Gulf of Lion and sometimes it was all right and other times it was a bust, which in terms of money meant that on the average day, if we were lucky, we made enough to pay our tab, and on bad days Raoul had to give us our toothpicks on credit. The bad streak got to be so worrisome that one night, out at sea, the skipper said maybe the Pirate was bad luck and everything was his fault. He just came out and said it, the way somebody might say it was raining, or he was hungry. And then the other fishermen said that if that was the way it was, why not throw the Pirate overboard right there, and then say at port that he was so drunk he'd fallen in? We were all talking about it for a while, half joking and half serious. Good thing the Pirate was too drunk to realize what the rest of us were saying. Around that time, too, the gendarmerie bastards came to see me at the cave. I was supposed to stand trial in a town near Albi for having ripped off a supermarket. This had happened two years before and all I'd taken was a loaf of bread, some cheese, and a can of tuna. But you can't outrun the long arm of the law. Every night I'd get drunk with my friends at Raoul's and shoot my mouth off about the police (even if I recognized some gendarme at the next table, drinking his pastis), society, and the way the justice system was always on your back, and I would read articles out loud from the magazine Hard Times . The people who sat at my table were fishermen, professional and amateur, and lots of young guys like me, city boys, summer fauna, washed up in Port-Vendres until further notice. One night, a girl whose name was Marguerite and whom I wanted to sleep with started to read a poem by Robert Desnos. I didn't know who the fuck Robert Desnos was, but other people at my table did, and anyway the poem was good, it got to you. We were sitting at an outside table, and lights were shining in the windows of the houses in town, but there wasn't even a cat on the streets and all we could hear was the sound of our own voices and a faraway car on the road to the station, and we were alone, or so we thought, but we hadn't seen (or at least I hadn't seen) the guy sitting at the farthest table. And it was after Marguerite read us the poem by Desnos-in that moment of silence after you hear something truly beautiful, the kind of moment that can last a second or two or your whole life, because there's something for everyone on this cruel earth-that the guy across the café got up and came over and asked Marguerite to read another poem. Then he asked if he could join us, and when we said sure, why not, he went to get his coffee from his table and then he emerged from the dark (because Raoul is always saving on electricity) and sat down with us and started to drink wine like us and bought us a couple of rounds, although he didn't look like he had money, but we were all broke so what could we do? we let him pay.

Around four in the morning we said our good nights. The Pirate and I headed for El Borrado. On our way out of Port-Vendres, we walked along quickly, singing as we walked. Then, where the road stops being a road and turns into a path that winds through the rocks to the caves, we slowed down, because even drunk as we were, we both knew one false step in the dark could be fatal with the waves breaking down below. There's usually plenty of noise along that path at night, but on this particular night it was mostly quiet, and for a while all we could hear was the sound of our footsteps and the gentle surf on the rocks. But then I heard a different kind of noise and I don't know why but I got the feeling there was someone behind us. I stopped and turned around, and looked into the dark, but I didn't see anything. A few feet ahead of me, the Pirate had stopped too and was standing there listening. Neither of us spoke, or even moved, and we just waited. From very far away came the whisper of a car and a muffled laugh, as if the driver had lost his mind. And still we didn't hear the noise that I'd heard, which was the sound of footsteps. It must have been a ghost, I heard the Pirate say, and we both started walking again. At the time, it was just him and me in the caves, because Mahmoud's cousin or uncle had come to get him so he could help get ready for the harvest in some village near Montpellier. Before we went to bed the Pirate and I smoked a cigarette, looking out to sea. Then we said good night and went off to our caves. I spent a while thinking about my stuff, the trip I had to make to Albi, the Isobel 's bad streak, Marguerite and the Desnos poems, an article about the Baader-Meinhof group I'd read that morning in Libération . Just when my eyes were closing I heard it again, the footsteps coming closer, stopping, the shadowy figure that made the footsteps and watched the dark mouths of caves. It wasn't the Pirate, that much I knew, I knew the Pirate's walk and it wasn't him. But I was too tired to get out of my sleeping bag or maybe I was already asleep and still hearing the footsteps, and at any rate, I thought that whoever was making the noise was no threat to me, no threat to the Pirate, and if it was somebody looking for a fight then he'd find one, but for that to happen he would have to come right into our caves and I knew that the stranger wouldn't come in. I knew he was just looking for an empty cave of his own where he could sleep.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Savage Detectives»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Savage Detectives» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Savage Detectives» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.