‘But you didn’t publish?’

‘The letter was just the beginning. It hinted at things much greater. I could have published, of course; I would go back to the archive, pretend to find it again, announce my discovery. But then I risked being left with the hook while someone else walked off with the fish. And I was jealous. I was like an old man with a young wife – except I was twenty-four and she was five hundred years old. I hid her away. My secret.’

While he spoke, he spun one of the threads of his blanket around the knuckle of his index finger, so tight the tip went white. He didn’t seem to notice.

‘I guarded my privacy. But not well enough. I was a young man: I had women to impress, rival scholars – who sometimes were also rivals in love – to outshine. I hinted; I made remarks; I allowed speculation. I was careless. I thought I was very clever.

‘Then one day a man came to see me. A young priest, Father Nevado. He came to my house. He was thin – we all were then, but he was thinner; he had red lips, like a vampire. He told me he had come from Italy, though he was obviously Spanish. From this I deduced he worked for the Vatican. ‘He told me, “I have heard rumours you have made a remarkable discovery.”’

‘“A letter from a man who complains that the Church has stolen something from him,” I said. I was arrogant. “Have you come to give it back?”

‘The priest’s eyes were like black ice. “The letter is the property of the Holy Church.”

‘He looked at me then. I tell you, I had watched dead-eyed Russian soldiers march into our guns until they choked them with their own blood. I had watched them shoot children and rape girls in the street. They had not frightened me as much as this priest did when he looked at me.

‘ “You will give me the letter,” he said. “You will give me all the copies you have made, including translations. You will give me the name of every person you have told about it. You will never mention it again; you will forget it ever existed.”

‘He broke me right there. I was a medieval historian; I knew what the Church could do to its enemies. Even in the twentieth century. It was in his voice. His eyes. I gave him the letter and all my notes.

‘ “If you ever tell anyone of this, you will surely suffer the torments of the damned,” he told me.

‘And so I kept silent. For ten years I devoted myself to my work. I completed my thesis and found a position at a provincial university. I attended seminars and workshops; I invited colleagues to dinner and flattered their wives; I reviewed obsequiously. I married. But my wound never healed.

‘I wrote a book. A small book, interesting only to scholars, if anyone. But I was proud of it. To me, it was vindication. The priest had taken the treasure that would have elevated my career to Olympian heights, but I had clawed myself up nonetheless. And I could not resist a small crow of triumph.

‘It was a footnote. Nothing more: a passing reference, so obscure no reader would even notice it. Just for my own pride.

‘Two weeks before the book was to be published, my editor called me to his office. He polished his spectacles; he was very regretful. He said that very serious allegations of plagiarism had been made against my work.

‘ “But there is no plagiarism in my book,” I protested. You must understand, to an academic it is like being accused of harming your children. I had sweated five years of blood to make that book.

‘ “Surely there is not,” said my editor. “But they are suing us for a large sum of money and if we lose we will be bankrupt. Your book is important, but I cannot risk all our other authors for you.”

‘ “Then what do we do?”

‘ “They require that we recall all copies and pulp them. They are not vindictive men; they have even offered to help pay for the costs of destruction.”

‘ “Who?” I demanded. “Who are these men who say what will or will not be published?” I guessed, of course. “Was it the priest?”

‘My editor played with his pen. “Make sure you bring in the advance copies you have at your house. We must account for every one.”

‘Three days later, I drove home from a dinner party with my wife. It was late, an icy night. Perhaps I had had a little too much schnapps – but in those days, everybody did. I came around a corner. Some fool had skidded and abandoned his car in the middle of the road. I had no chance.’

Olaf folded his hands. ‘My wife died at once. I spent six months in hospital and came out in a wheelchair I have never left.’

‘Did they catch the people who did it?’ said Emily.

‘The car was stolen. The police said it was youths, joyriders who panicked when the car skidded. I did not believe them.

‘After that I abandoned my history. It was too dangerous. I wrote some tourist guides to Mainz; I volunteered at the museum. Those people took away my past, my present, my future. I lived forty years waiting to die. I never spoke of it.’

‘But you told Gillian,’ said Nick.

The old man rocked back in his wheelchair. ‘My second wife died five years ago – from the cancer. I was almost glad: at least I could not blame myself. We have no children. There is nothing more they can take from me. When Gillian Lockhart contacted me, I thought it was my last chance. My wound still has not healed.’

‘How did she find you?’

Olaf chuckled. ‘Do you know the Hawking paradox?’

‘As in Stephen Hawking?’ said Nick. ‘His calculations showed that when matter enters a black hole all information about it is destroyed. But that contradicts a fundamental law of physics: that information cannot be destroyed.’

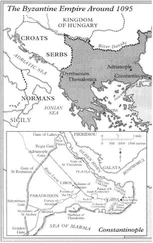

‘Dr Hawking was proved wrong. Even in a black hole, some information survives. So also with my little book. Somewhere, somehow, a few copies leaked out of the black hole Father Nevado made for them. One sat on a library shelf – who knows where – fifty years. Waiting. Until, it seems, an Internet company started digitising this library’s collection as part of a project to accumulate all knowledge. If Father Nevado knew about it, he would probably tear down all the World Wide Web to get rid of it. But even he cannot police everything. Gillian found it first. Then she found me. I sat in this same church and told her what I have told you. Like me fifty years ago, she was too stubborn to hear the warnings.’

‘You told her about the letter?’

‘About the letter – yes. But for her it was more important to learn about the library.’

‘Which library?’ Nick felt like a drunk wandering across a frozen lake: slipping and skidding, with only the faintest idea of the airless depths beneath.

‘The Bibliotheca Diabolorum. The Library of Devils.’

The blue light seemed to wrap Nick closer. Emily slid along the bench, pressing against him. By the altar, a young priest was reciting a litany.

‘You know of it?’

Nick and Emily shook their heads.

‘Few people have even heard its name. It is a construction, a myth. A hell for condemned books. The last curse of the thwarted scholar when all his efforts to find a book have failed: it must have gone to the Devils’ Library.’

‘Does it exist?’

‘It must.’ Olaf’s hands were trembling. He knitted his fingers together. ‘They almost killed me to protect it. That was the footnote in my book: “We should consider the possibility that some books from Johann Fust’s collection may have been confiscated, perhaps to the so-called Devils’ Library.” That was why they killed my wife.’

‘Was that what Fust’s letter said?’

‘Not precisely. You can see yourself.’

Olaf twisted in his seat and began fiddling with his wheel-chair. It was an old contraption, with wooden armrests screwed to a metal frame. One of the screws was loose. Olaf scrabbled underneath and slid out a piece of paper folded over and over, concertina-style, so as to be no wider than the armrest.

Читать дальше