‘What, exactly?’

‘He pieced things together.’ She shot Nick a shy grin to see if he’d got the joke. ‘Movable type. He worked out a technique to cast individual letters on blocks of metal, then put them together into words, sentences, eventually an entire Bible – and print it out.’

Nick tried to imagine assembling a whole Bible letter by letter. ‘Must have taken a long time.’

‘Years, probably. But the only alternative was handwriting. Once he had the page set up he could print off as many copies as he wanted. Then he’d take it apart and reuse the letters to create a whole different page. Infinitely flexible, while at the same time creating a product that was completely standardised and could be replicated as often as people wanted it. It was probably the greatest step forward in the communication of information between the alphabet and the Internet.’

‘And when was this?’

‘The mid-fifteenth century.’

‘The same time as the Master of the Playing Cards.’

Emily held up the book from the library. There was nothing on the front cover except a grazing stag embossed in gold. Nick recognised it at once from the suit of deer. Emily turned the book spine on.

‘Gutenberg and the Master of the Playing Cards,’ Nick read.

‘I came across it when I was looking into Gillian’s card, back in New York. You’re not the first one to wonder about a connection. There’s an illuminated copy of the Gutenberg Bible at Princeton whose illustrations look like copies of the playing cards. The author of this book suggested that perhaps there was a partnership between Gutenberg and the Master to produce illustrations for the Bibles. The man who perfected printing text and the man who perfected printing engravings. It’s a seductive idea.’

‘Is there any evidence for it?’

‘Only circumstantial. Most of the arguments in this book have been picked apart.’ Emily stared at the printout as if she couldn’t quite believe it. ‘Until this.’

A siren howled in the distance. Nick tried to concentrate. ‘Isn’t it pretty similar to the bestiary we found in Brussels?’

‘The bestiary is handwritten; this is printed. You can see how regular the type is, how perfectly straight the lines are. The same with the illustrations. The pictures in the bestiary have been hand-painted. It’s hard to be certain with the reconstruction, but it looks as if the one here has been printed like the cards.’

The siren was getting louder. Nick wiped the window and looked out. The only other car in the lay-by was a silver Opel parked at the far end. Its driver stood with his back to them, relieving himself into the snow under the trees.

‘So we’ve got a printed picture that we know dates from the mid-fifteenth century and some printed text. How do you make the leap to Gutenberg?’

Emily pointed to the letters. ‘Gutenberg was the first. He didn’t just invent the printing press; he had to invent, or perfect, everything. The alloys used to cast the types and the tools for making them. The processes for putting together the pages and then holding them in place. The inks.’ She suddenly trailed off.

‘The inks…?’

The siren had swelled to an ear-splitting whoop. An ambulance sped past behind them, blasting its horn to clear the traffic. Nick exhaled a deep breath that promptly crystallised on the windscreen. Emily didn’t seem to have noticed.

‘That must be what alerted Gillian.’ She pulled out the playing card and scrutinised it. ‘Here.’

She pointed to a cluster of dark spots in the lower corner of the card.

‘Gutenberg’s ink is famous for its lustre. It doesn’t fade; it’s as dark and deep now as the day he pulled it off the press.’

‘How come?’

‘No one knows. Even among early printed books it’s unique. People have tried everything to unravel his recipe – even analysing it with spectrometers.’

‘PIXE,’ said Nick. ‘Vandevelde.’

‘Gillian must have noticed the ink and guessed what it was. Vandevelde would have confirmed it.’

‘Before they got to him. But how did you figure it out?’

‘The font. Gutenberg invented that too. It wasn’t a question of selecting Times New Roman or Arial; he had to design every letter and then cut it into blocks of metal for casting. In early printed books, each typeface is as unique as handwriting.’

She ran a finger over the reassembled letters. ‘This is the grandfather of them all. The type he used for his masterpiece, the Gutenberg Bible. So far as we’ve ever known, that was the only major book he printed.’ She caressed the printout like an infant. ‘This is like finding an autographed copy of a lost Shakespeare play with illustrations by Rembrandt.’

‘We haven’t found it yet,’ Nick reminded her. ‘All we’ve got is a printout of a reconstruction of one page that a guy tore up in Strasbourg. I don’t think that was original either, unless Gutenberg printed it off on office paper.’

‘You pointed a gun at him and the only thing he cared about was destroying that piece of paper. It’s a true copy of something. Somewhere.’

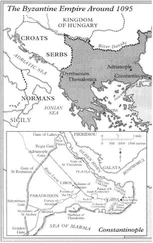

Mainz

For such a large building, the Hof zum Gutenberg was surprisingly unassuming: the narrow street offered no position where you could take in its full size. At ground level it blended unnoticed into its neighbour, while the greater part slipped around a corner into an alley. You would have had to crane your head far back to see the peaked gable overhead: most people were too occupied dodging livestock, dung and the pelts hanging from hooks outside the furrier’s shop opposite to look much higher than their own feet. It was a perfect home for what went on within.

‘I hear you have taken a new name since you returned,’ Fust said.

‘Gutenberg.’ I had jettisoned my father’s name and assumed that of my first and last home. It announced me as a man of property, which proved useful in some of my dealings; but more than that it anchored me. I belonged here.

As we stepped over the threshold I looked up, as I always did, at the crest carved into the keystone of the arch. It showed a hunched pilgrim in a high conical cap, bent almost double under the weight of the load he carried hidden beneath his cloak. What was that burden, I wondered? He leaned on a stick, while the other hand held out a begging bowl for alms. I did not know how it had become our family emblem – even my father could not say. But I felt, as always, a kinship – a weary pilgrim still begging alms to finish his journey.

I had been busy since my return. The front rooms which my father had used to display his cloths and wares had been boarded up. Now they were crowded with furniture, pushed against walls or piled high as if readied for a move. Dust had already begun to settle.

I led Fust into another room, then down a short corridor past the pantry. We paused outside an iron-bound door that led into the rear wing.

‘What you see and what you hear – you swear by Mary and the saints you will not reveal it to anyone?’

Fust nodded. I opened the door.

In the middle of the room, three men sat at a table that had been moved there for the purpose. They were sipping wine, though none looked as if he was enjoying it. They knew what was at stake.

I introduced them.

‘Konrad Saspach of Strassburg, chest maker and carpenter. He makes our presses, which you will see presently.’

Saspach was one of the few men who had grown in my estimation since I’d known him. His beard was now white and bushy as a prophet’s, his hands so wizened it seemed impossible they could turn a lathe or make a saw cut so straight. He had always been on the periphery of our enterprise, but when I asked him to come from Strassburg he had agreed willingly.

Читать дальше