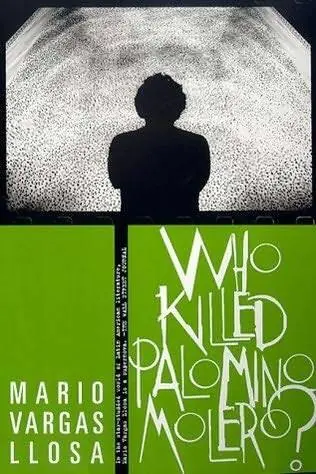

Mario Vargas Llosa

Who Killed Palomino Molero?

© 1987

“Sons of bitches.” Lituma felt the vomit rising in his throat. “Kid, they really did a job on you.”

The boy had been both hung and impaled on the old carob tree. His position was so absurd that he looked more like a scarecrow or a broken marionette than a corpse. Before or after they killed him, they slashed him to ribbons: his nose and mouth were split open; his face was a crazy map of dried blood, bruises, cuts, and cigarette burns. Lituma saw they’d even tried to castrate him; his testicles hung down to his thighs. He was barefoot, naked from the waist down, with a ripped T-shirt covering his upper body. He was young, thin, dark, and bony. Under the labyrinth of flies buzzing around his face, his hair glistened, black and curly.

The goats belonging to the boy who’d found the body were nosing around, scratching around the field looking for something to eat. Lituma thought they might begin to gnaw on the dead man’s feet at any moment.

“Who the fuck did this?” he stammered, holding back his gorge.

“I don’t know,” said the boy. “Don’t get mad at me, it’s not my fault. You should be glad I told you about it.”

“I’m not mad at you. I’m mad that anybody could be bastard enough to do something like this.”

The boy must have had the shock of his life this morning when he drove his goats over the rocky field and stumbled onto this horror. But he did his duty: he left his herd browsing among the rocks around the corpse and ran to the police station in Talara. Which was quite a feat because Talara was a good hour’s walk from the pasture. Lituma remembered his sweaty face and his scared voice when he walked through the station-house door:

“They killed a guy over on the road to Lobitos. I can take you there if you want, but we have to go now because I left my goats all alone and somebody could steal them.”

Luckily, no goats were stolen. As he was getting over the jolt of seeing the body, Lituma had noticed the boy counting his goats on his fingers. He heard him breathe a sigh of relief: “All here.”

“Holy Mother of God!” exclaimed the taxi driver. “What the hell is this?”

On the way, the boy had described, more or less, what they were going to see, but it was one thing to imagine it and quite another to see it and smell it…The corpse stank to high heaven. The sun was boring holes through the rocks and through their very skulls. He must have been rotting at a record pace.

“Will you help me get him down, buddy?”

“Why not?” grunted the taxi driver, crossing himself. He spit at the carob tree. “If someone had told me what the Ford was going to be carrying, I’d never of bought it. You and the lieutenant take advantage of me because I’m such a nice guy.”

Jerónimo had the only taxi in Talara. His old van, as big and black as a hearse, passed freely through the gate that separated the town from the zone where the foreigners who were employed by the International Petroleum Company lived and worked. Lieutenant Silva and Lituma used the taxi whenever they had to go anywhere too far to use horses or bicycles-the only transport available at the Guardia Civil post. The driver moaned and complained every time they called him, saying they made him lose money, despite the fact that the lieutenant always paid for the gasoline himself.

“Wait, Jerónimo, I just remembered we can’t touch him until the judge comes and holds his inquest.”

“Which means I’ll be making this little trip again,” croaked the old man. “Either the judge pays me or you find another sucker.”

Just then, he tapped himself on the forehead, opened his eyes wide, and looked the corpse in the face. “Wait a minute! I know this guy!”

“Who is he?”

“One of the boys they brought to the air base among the last bunch of recruits.” The old man’s face lit up. “That’s right. The guy from Piura who sang boleros.”

“He sang boleros? Then he’s got to be the guy I told you about,” Mono said again.

“He is. We checked; he’s the same guy. Palomino Molero, from Castilla. But that doesn’t tell us who killed him.”

They were near the stadium in La Chunga ’s little bar. There must have been a prizefight in progress because they could hear the shouts of the fans. Lituma had come to Piura on his day off; a truck driver from the I.P.C. brought him that morning and was going back to Talara at midnight. Whenever he came to Piura, Lituma went on the town with his cousins, José and Mono León, and with Josefino, a friend from the Gallinacera neighborhood. Lituma and the León brothers were from La Mangachería, but the long-standing rivalry between the two neighborhoods meant nothing to the four friends. They were so close they’d written their own theme song and called themselves the Unstoppables.

“Figure this one out and they’ll make you a general, Lituma,” wisecracked Mono.

“It’s going to be tough. Nobody knows anything, nobody saw anything, and the worst part is that the authorities won’t lift a finger to help.”

“Wait a minute, aren’t you the authorities over in Talara?” asked Josefino, genuinely surprised.

“Lieutenant Silva and I are the police authority. The authority I’m talking about is the Air Force. That skinny kid was in the Air Force, so if they don’t help us, who the fuck will?”

Lituma blew the foam off his beer and took a swallow, opening his mouth like a crocodile. “Motherfuckers. If you guys had seen what they did to the kid, you wouldn’t be grinning your way down to the whorehouse like this. You’d understand why I can’t think about anything else.”

“We do understand,” said Josefino. “But talking about a corpse all the time is boring. Why don’t you forget about the guy, Lituma? He’s dead.”

“That’s what you get for becoming a cop,” said José. “Work is a disease. Besides, you’re no good at that stuff. A cop should have a heart made of stone, because he has to be a motherfucker sometimes. And you’re so damn sentimental.”

“It’s true, I am. I just can’t stop thinking about that skinny kid. I have nightmares, I think someone’s pulling off my balls the way they did to him. His balls were hanging down to his knees, smashed as flat as a pair of fried eggs.”

“Did you touch them?” Mono asked, laughing.

“Talk about eggs and balls, did Lieutenant Silva screw that fat woman yet?” José asked.

“We’ve been on pins and needles ever since you told us about it,” added Josefino. “Did he screw her or not?”

“At the rate he’s going, he’ll never screw her.”

José got up from the table. “Okay, let’s go to the movies. Before midnight the whorehouse is like a funeral parlor. They’re showing a cowboy film at the Variety with Rosita Quintana. The cop’s treating, of course.”

“Me? I don’t even have the dough for this beer. You’ll let me pay later, won’t you, Chunguita?”

“Maybe your mama will let you pay later,” answered La Chunga, looking bored.

“I figured you’d say something like that. I just wanted to screw around.”

“Go screw around with your mama.”

“Two points for La Chunga; zero for Lituma,” Mono announced. “ La Chunga wins.”

“Don’t get steamed, Chunguita. Here’s what I owe you. And lay off my mom: she’s dead and buried over in Simbilá.”

La Chunga, a tall, sour woman of uncertain age, snatched up the money, counted it, and gave back the change as the Unstoppables were leaving.

Читать дальше