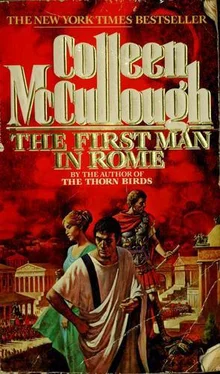

Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:1. First Man in Rome

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1. First Man in Rome: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «1. First Man in Rome»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

1. First Man in Rome — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «1. First Man in Rome», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Word came to Marius that the Germans showed no sign of moving south into the Roman province of Gaul-across-the-Alps, save for the Cimbri, who had crossed to the western bank of the Rhodanus and were keeping clear of the Roman sphere. The Teutones, said Marius's agent's report, were wandering off to the northwest, and the Tigurini-Marcomanni-Cherusci were back among the Aedui and Ambarri looking as if they never intended to move. Of course, the report admitted, the situation could change at any moment. But it took time for eight hundred thousand people to gather up their belongings, their animals, and their wagons, and start moving. Gaius Marius need not expect to see any Germans coming south down the Rhodanus before May or June. If they came at all. It didn't really please Gaius Marius, that report. His men were excited and primed for a good fight, his legates were anxious to do well, and his officers and centurions had been toiling to produce a perfect military machine. Though Marius had known since landing in Italy the previous December that there was a German interpreter saying the Germans were at loggerheads with each other, he hadn't really believed they would not resume their southward progress through the Roman province. The Germans having annihilated an enormous Roman army, it was logical, natural, and proper for them to take advantage of their victory and move into the territory they had in effect won by force of arms. Settle in it, even. Otherwise, why give battle at all? Why emigrate? Why anything? "They are a complete mystery to me!" he cried, chafing and frustrated, to Sulla and Aquillius after the report came. "They're barbarians," said Aquillius, who had earned his place as senior legate by suggesting that Marius be made consul, and now was very eager to go on proving his worth. But Sulla was unusually thoughtful. "We don't know nearly enough about them," he said. "I just remarked about that!" snapped Marius. "No, I was thinking along different lines. But" he slapped his knees "I'll go on thinking about things for a bit longer, Gaius Marius, before I speak. After all, we don't really know what we'll find when we cross the Alps." "That one thing we do have to decide," said Marius. "What?" asked Aquillius. "Crossing the Alps. Now that we've been assured the Germans are not going to prove a threat before May or June at the very earliest, I'm not in favor of crossing the Alps at all. At least, not by the usual route. We're moving out at the end of January with a massive baggage train. So we're going to be slow. The one thing I'll say for Metellus Dalmaticus as Pontifex Maximus is that he's a calendar fanatic, so the seasons and the months are in accord. Have you felt the cold this winter?" he asked Sulla. "Indeed I have, Gaius Marius." "So have I. Our blood is thin, Lucius Cornelius. All that time in Africa, where frosts are short-lived, and snow is something you see on the highest mountains. Why should it be any different for the troops? If we cross through the Mons Genava Pass in winter, it will go very hard on them.'' "After furlough in Campania, they'll need hardening," said Sulla unsympathetically. "Oh, yes! But not by losing toes from frostbite and the feeling in their fingers from chilblains. They've got winter issue but will the cantankerous cunni wear it?" "They will, if they're made." "You are determined to be difficult," said Marius. "All right then, I won't try to be reasonable I'll simply issue orders. We are not taking the legions to Gaul-across-the-Alps by the usual route. We're going to march along the coast the whole long way." "Ye gods, it'll take an eternity!" said Aquillius. "How long is it since an army traveled to Spain or Gaul along the coast?" Marius asked Aquillius. "I can't remember an occasion when an army has!" "And there you have it, you see!" said Marius triumphantly. "That's why we're going to do it. I want to see how difficult it is, how long it takes, what the roads are like, the terrain everything. I'll take four of the legions in light marching order, and you, Manius Aquillius, will take the other two legions plus the extra cohorts we've managed to scrape together, and escort the baggage train. If when they do turn south, the Germans head for Italy instead of for Spain, how do we know whether they'll go over the Mons Genava Pass into Italian Gaul, or whether they'll head as they'll see it, anyway straight for Rome along the coast? They seem to have precious little interest in discovering how our minds work, so how are they going to know that the quickest and shortest way to Rome is not along the coast, but over the Alps into Italian Gaul?" His legates stared at him. "I see what you mean," said Sulla, "but why take the whole army? You and I and a small squadron could do it better." Marius shook his head vigorously. "No! I don't want my army separated from me by several hundred miles of impassable mountains. Where I go, my whole army goes." So at the end of January Gaius Marius led his whole army north along the coastal Via Aurelia, taking notes the entire way, and sending curt letters back to the Senate demanding that repairs be made to this or that stretch of the road forthwith, bridges built or strengthened, viaducts made or refurbished. "This is Italy," said one such missive, "and all available routes to the north of the peninsula and Italian Gaul and Liguria must be kept in perfect condition; otherwise we may rue the day." At Pisae, where the river Arnus flowed into the sea, they crossed from Italy proper into Italian Gaul, which was a most peculiar area, neither officially designated a province nor governed like Italy proper. It was a kind of limbo. From Pisae all the way to Vada Sabatia the road was brand-new, though work on it was far from finished; this was Scaurus's contribution when he had been censor, the Via Aemilia Scauri. Marius wrote to Marcus Aemilius Scaurus Princeps Senatus:

You are to be commended for your foresight, for I regard the Via Aemilia Scauri as one of the most significant additions to the defense of Rome and Italy since the opening-up of the Mons Genava Pass, and that is a very long time ago, considering that it was there for Hannibal to use. Your branch road to Dertona is vital strategically, for it represents the only way across the Ligurian Apennines from the Padus to the Tyrrhenian coast Rome's coast. The problems are enormous. I talked to your engineers, whom I found to be a most able group of men, and am happy to relay to you their request that additional funds be found to increase the work force on this piece of road. It needs some of the highest viaducts not to mention the longest I have ever seen, more indeed like aqueduct construction than road building. Luckily there are local quarry facilities to provide stone, but the pitifully small work force is retarding the pace at which I consider the work must progress. With respect, may I ask that you use your formidable clout to pry the money out of the House and Treasury to speed up this project? If it could be completed by the end of this coming summer, Rome may rest easier at the thought that a mere fifty-odd miles of road may save an army several hundreds.

"There," said Marius to Sulla, "that ought to keep the old boy busy and happy!" "It will, too," said Sulla, grinning. The Via Aemilia Scauri ended at Vada Sabatia; from that point on there was no road in the Roman sense, just a wagon trail which followed the line of least resistance through an area where very high mountains plunged into the sea. "You're going to be sorry you chose this way," said Sulla. "On the contrary, I'm glad. I can see a thousand places where ambush is possible, I can see why no one in his right mind goes to Gaul-across-the-Alps this way, I can see why our Publius Vagiennius who hails from these parts could climb a sheer wall to find his snail patch, and I can see why we need not fear that the Germans will choose this route. Oh, they might start out along the coast, but a couple of days of this and a fast horseman going ahead will see them turn back. If it's difficult for us, it's impossible for them. Good!" Marius turned to Quintus Sertorius, who, in spite of his very junior status, enjoyed a privileged position nothing save merit had earned him. "Quintus Sertorius, my lad, whereabouts do you think the baggage train might be?" he asked. "I'd say somewhere between Populonia and Pisae, given the poor condition of the Via Aurelia," Sertorius said. "How's your leg?" "Not up to that kind of riding." Sertorius seemed always to know what Marius was thinking. "Then find three men who are, and send them back with this," said Marius, drawing wax tablets toward him. '' You' re going to send the baggage train up the Via Cassia to Florentia and the Via Annia to Bononia, and then across the Mons Genava Pass," said Sulla, sighing in satisfaction. "We might need all those beams and bolts and cranes and tackle yet," said Marius. He smacked the backs of his fingers down on the wax to produce a perfect impression from his seal ring, and closed the hinged leaves of the tablet. "Here," he said to Sertorius. "And make sure it's tied and sealed again; I don't want any inquisitive noses poking inside. It's to be given to Manius Aquillius himself, understood?" Sertorius nodded and left the command tent. "As for this army, it's going to do a bit of work as it goes," Marius said to Sulla. "Send the surveyors out ahead. We'll make a reasonable track, if not a proper road." In Liguria, like other regions where the mountains were precipitous and the amount of arable land small, the inhabitants tended to a pastoral way of life, or else made a profession out of banditry and piracy, or like Publius Vagiennius took service in Rome's auxiliary legions and cavalry. Wherever Marius saw ships and a village clustered in an anchorage and deemed the ships more suited to raiding and boarding than to fishing, he burned both ships and village, left women, old men, and children behind, and took the men with him to labor improving the road. Meanwhile the reports from Arausio, Valentia, Vienne, and even Lugdunum made it increasingly clear as time went on that there would be no confrontation with the Germans this year. At the beginning of June, after four months on the march, Marius led his four legions onto the widening coastal plains of Gaul-across-the-Alps and came to a halt in the well-settled country between Arelate and Aquae Sextiae, in the vicinity of the town of Glanum, south of the Druentia River. Significantly, his baggage train had arrived before him, having spent a mere three and a half months on the road. He chose his campsite with extreme care, well clear of arable land; it was a large hill having steep and rocky slopes on three sides, several good springs on top, and a fourth side neither too steep nor too narrow to retard swift movement of troops in or out of a camp atop the hill. "This is where we are going to be living for many moons to come," he said, nodding in satisfaction. "Now we're going to turn it into Carcasso." Neither Sulla nor Manius Aquillius made any comment, but Sertorius was less self-controlled. "Do we need it?" he asked. "If you think we're going to be in the district for many moons to come, wouldn't it be a lot easier to billet the troops on Arelate or Glanum? And why stay here? Why not seek the Germans out and come to grips with them before they can get this far?" "Well, young Sertorius," said Marius, "it appears the Germans have scattered far and wide. The Cimbri, who seemed all set to follow the Rhodanus to its west, have now changed their minds and have gone to Spain, we must presume around the far side of the Cebenna, through the lands of the Arverni. The Teutones and the Tigurini have left the lands of the Aedui and gone to settle among the Belgae. At least, that's what my sources say. In reality, I imagine it's anyone's guess." "Can't we find out for certain?" asked Sertorius. "How?" asked Marius. "The Gauls have no cause to love us, and it's upon the Gauls we have to rely for our information. That they've given it to us so far is simply because they don't want the Germans in their midst either. But on one thing you can rely: when the Germans reach the Pyrenees, they'll turn back. And I very much doubt that the Belgae will want them any more than the Celtiberians of the Pyrenees. Looking at a possible target from the German point of view, I keep coming back to Italy. So here we stay until the Germans arrive, Quintus Sertorius. I don't care if it takes years." "If it takes years, Gaius Marius, our army will grow soft, and you will be ousted from the supreme command," Manius Aquillius pointed out. "Our army is not going to grow soft, because I am going to put it to work," said Marius. "We have close to forty thousand men of the Head Count. The State pays them; the State owns their arms and armor; the State feeds them. When they retire, I shall see to it that the State looks after them in their old age. But while they serve in the State's army, they are nothing more nor less than employees of the State. As consul, I represent the State. Therefore they are my employees. And they are costing me a very large amount of money. If all they are required to do in return is sit on their arses waiting to fight a battle, compute the enormity of the cost of that battle when it finally comes." The eyebrows were jiggling up and down fiercely. "They didn't sign a contract to sit on their arses waiting for a battle, they enlisted in the army of the State to do whatever the State requires of them. Since the State is paying them, they owe the State work. And that's what they're going to do. Work! This year they're going to repair the Via Domitia all the way from Nemausus to Ocelum. Next year they're going to dig a ship canal all the way from the sea to the Rhodanus at Arelate." Everyone was staring at him in fascination, but for a long moment no one could find anything to say. Then Sulla whistled. "A soldier is paid to fight!" "If he bought his gear with his own money and he expects nothing more from the State than the food he eats, then he can call his own tune. But that description doesn't fit my lot," said Gaius Marius. "When they're not called upon to fight, they'll do much-needed public works, if for no other reason than it will give them to understand that they're in service to the State in exactly the same way as a man is to any employer. And it will keep them fit!" "What about us?" asked Sulla. "Do you intend to turn us into engineers?" "Why not?" asked Marius. "I'm not an employee of the State, for one thing," said Sulla, pleasantly enough. "I give my time as a gift, like all the legates and tribunes." Marius eyed him shrewdly. "Believe me, Lucius Cornelius, it's a gift I appreciate," he said, and left it at that.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «1. First Man in Rome» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.