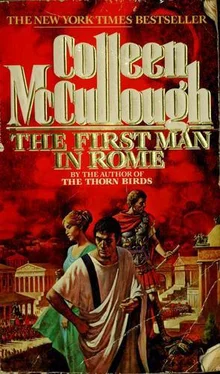

Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:1. First Man in Rome

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1. First Man in Rome: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «1. First Man in Rome»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

1. First Man in Rome — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «1. First Man in Rome», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Caepio wouldn't even hear Cotta out, let alone listen to the voice of reason. "Here is where I stay" was all he said. So Cotta rode on without pausing to slake his thirst in Caepio's half-finished camp, determined that he would reach Gnaeus Mallius Maximus by noon at the latest. At dawn, while Cotta and Caepio were failing to see eye to eye, the Germans moved. It was the second day of October, and the weather continued to be fine, no hint of chill in the air. When the front ranks of the German mass came up against Aurelius's camp walls, they simply rolled over them, wave after wave after wave. Aurelius hadn't really understood what was happening; he naturally assumed there would be time to get his cavalry squadrons into the saddle that the camp wall, extremely well fortified, would hold the Germans at bay for long enough to lead his entire force out the back gate of the camp, and to attempt a flanking maneuver. But it was not to be. There were so many fast-moving Germans that they were around all four sides of the camp within moments, and poured over every wall in thousands. Not used to fighting on foot, Aurelius's troopers did their best, but the engagement was more a debacle than a battle. Within half an hour hardly a Roman or an auxiliary was left alive, and Marcus Aurelius Scaurus was taken captive before he could fall on his sword. Brought before Boiorix, Teutobod, and the rest of the fifty who had come to parley, Aurelius conducted himself superbly. His bearing was proud, his manner insufferably haughty; no indignity or pain they could inflict upon him bowed his head or caused him to flinch. So they put him in a wicker cage just large enough to hold him, and made him watch while they built a pyre of the hottest woods, and set fire to it, and let it burn. Aurelius watched, legs straight, no tremor in his hands, no fear on his face, not even clinging to the bars of his little prison. It being no part of their plan that Aurelius should die from inhaling smoke or that he should die too quickly amid vast licks of flame they waited until the pyre had died down, then winched the wicker cage over its very center, and roasted Aurelius alive. But he won, though it was a lonely victory. For he would not permit himself to writhe in agony, or cry out, or let his legs buckle under him. He died every inch the Roman nobleman, determined that his conduct would show them the real measure of Rome, make them take heed of a place which could produce men such as he, a Roman of the Romans. For two days more the Germans lingered by the ruins of the Roman cavalry camp, then the move southward began again, with as little planning as before. When they came level with Caepio's camp they just kept on walking south, thousands upon thousands upon thousands, until the terrified eyes of Caepio's soldiers lost all hope of counting them, and some decided to abandon their armor and swim for the west bank of the river, and safety. But that was a last resort Caepio intended to keep exclusively for himself; he burned all but one of his small fleet of boats, posted a heavy guard all the way down the riverbank, and executed any men who tried to escape. Marooned in a vast sea of Germans, the fifty-five thousand soldiers and noncombatants in Caepio's camp could do nothing but wait to see if the flood would pass them by unharmed. By the sixth day of October, the German front ranks had reached the camp of Mallius Maximus, who preferred not to keep his army pent up within its walls. So he formed up his ten legions and marched them out onto the ground just to the north before the Germans, clearly visible, could surround his camp. He arrayed his troops across the flat ground between the riverbank and the first rise in the ground which heralded the tips of the tentacles of the Alps, even though their foothills were almost a hundred miles away to the east. The legions stood, all facing north, side by side for a distance of four miles, Mallius Maximus's fourth mistake; not only could he easily be outflanked since he possessed no cavalry to protect his exposed right but his men were stretched too thin. Not one word had come to him of conditions to the north, of Aurelius or of Caepio, and he had no one to disguise and send out into the German hordes, for all the available interpreters and scouts had been sent north with Aurelius. Therefore he could do nothing except wait for the Germans to arrive. Logically his command position was atop the highest tower of his fortified camp wall, so there he positioned himself, with his personal staff mounted and ready to gallop his orders to the various legions; among his personal staff were his own two sons, and the youthful son of Metellus Numidicus Piggle-wiggle, the Piglet. Perhaps because Mallius Maximus deemed Quintus Poppaedius Silo's legion of Marsi best disciplined and trained or perhaps because he deemed its men more expendable than Romans, even Roman rabble it stood furthest east of the line, on the Roman right, and devoid of any cavalry protection. Next to it was a legion recruited early in the year commanded by Marcus Livius Drusus, who had inherited Quintus Sertorius as his second-in-charge. Then came the Samnite auxiliaries, and next in line another Roman legion of early recruits; the closer the line got to the river, the more ill trained and inexperienced the legions became, and the more tribunes of the soldiers were there to stiffen them. Caepio Junior's legion of completely raw troops was stationed along the riverbank, with Sextus Caesar, also commanding raw troops, next to him. There seemed to be a slight element of plan about the German attack, which commenced two hours after dawn on the sixth day of October, more or less simultaneously upon Caepio's camp and upon Mallius Maximus's line of battle. None of Caepio's fifty-five thousand men survived when the Germans all around them simply turned inward on the three landward perimeters of the camp and spilled into it until the crush of men was so great the wounded were trampled underfoot along with the dead. Caepio himself didn't wait. As soon as he saw that his soldiers had no hope of keeping the Germans out, he hustled himself down to the water, boarded his boat, and had his oarsmen make for the western bank of the Rhodanus at racing speed. A handful of his abandoned men tried to swim to safety, but there were so many Germans hacking and hewing that no Roman had the time or the space to shed his twenty-pound shirt of mail or even untie his helmet, so all those who attempted the swim drowned. Caepio and his boat crew were virtually the sole survivors. Mallius Maximus did little better. Fighting valiantly against gargantuan odds, the Marsi perished almost to the last man, as did Drusus's legion fighting next to the Marsi. Silo fell, wounded in the side, and Drusus was knocked senseless by a blow from the hilt of a German sword not long after his legion engaged; Quintus Sertorius tried to rally the men from horseback, but there was no holding the German attack. As fast as they were chopped down, fresh Germans sprang in to replace them, and the supply was endless. Sertorius fell too, wounded in the thigh at just the place where the great nerves to the lower leg were most vulnerable; that the spear shore through the nerves and stopped just short of the femoral artery was nothing more nor less than the fortunes of war. The legions closest to the river turned and took to the water, most of them managing to doff their heavy gear before wading in, and so escape by swimming the Rhodanus to its far side. Caepio Junior was the first to yield to temptation, but Sextus Caesar was cut down by one of his own soldiers when he tried desperately to stop their retreat, and subsided into the melee with a mangled left hip. In spite of Cotta's protests, the six senators had been ferried across to the western bank before the battle began; Mallius Maximus had insisted that as civilian observers they should leave the field and observe from some place absolutely safe. "If we go down, you must survive to bring the news to the Senate and People of Rome," he said. It was Roman policy to spare the lives of all they defeated, for able-bodied warriors fetched the highest prices as slaves destined for labor, be it in mines, on wharves, in quarries, on building projects. But neither Celts nor Germans spared the lives of the men they fought, preferring to enslave those who spoke their languages, and only in such numbers as their unstructured way of life demanded. So when, after a brief inglorious hour of battle, the German host stood victorious on the field, its members passed among the thousands of Roman bodies and killed any they found still alive. Luckily this act wasn't disciplined or concerted; had it been, not one of the twenty-four tribunes of the soldiers would have survived the battle of Arausio. Drusus lay so deeply unconscious he seemed dead to every German who looked him over, and all of Quintus Poppaedius Silo showing from beneath a pile of Marsic dead was so covered in blood he too went undiscovered. Unable to move because his leg was completely paralyzed, Quintus Sertorius shammed dead. And Sextus Caesar, entirely visible, labored so loudly for breath and was so blue in the face that no German who noticed him could be bothered dispatching a life so clearly ending of its own volition. The two sons of Mallius Maximus perished as they galloped this way and that bearing their distracted father's orders, but the son of Metellus Numidicus Piggle-wiggle, young Piglet, was made of sterner stuff; when he saw the inevitability of defeat, he hustled the nerveless Mallius Maximus and some half-dozen aides who stood with him across the top of the camp ramparts to the river's edge, and there put them into a boat. Metellus Piglet's actions were not entirely dictated by motives of self-preservation, for he had his share of courage; simply, he preferred to turn that courage in the direction of preserving the life of his commander.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «1. First Man in Rome» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.