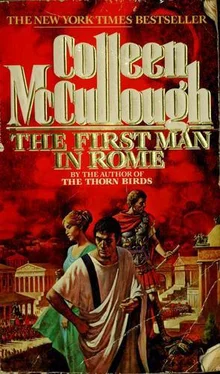

Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Colleen McCullough - 1. First Man in Rome» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:1. First Man in Rome

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1. First Man in Rome: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «1. First Man in Rome»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

1. First Man in Rome — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «1. First Man in Rome», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All in all, Jugurtha was well satisfied with the way things were going. Though he had suffered considerably from Marius's raids into the more settled parts of his realm, he knew none better that the sheer size of Numidia was his greatest advantage and protection. And the settled parts of Numidia, unlike other nations, mattered less to the King than the wilderness. Most of Numidia's soldiers, including the light-armed cavalry so famous throughout the world, were recruited among the peoples who lived a seminomadic existence far within the interior of the country, even on the far side of the mighty mountains in which the patient Atlas held up the sky on his shoulders; these peoples were known as Gaetuli and Garamantes; Jugurtha's mother belonged to a tribe of the Gaetuli. After the surrender of Vaga, the King made sure he kept no money or treasure in any town likely to be along the line of a Roman route march; everything was transferred to places like Zama and Capsa, remote, difficult to infiltrate, built as citadels atop unscalable peaks and surrounded by the fanatically loyal Gaetuli. And Vaga turned out to be no Roman victory; once again Jugurtha had bought himself a Roman, the garrison commander, Turpilius. Metellus's friend. Ha! However, something was changed. As the winter rains began to dwindle, Jugurtha became more and more convinced of this. The trouble was, he couldn't put his finger on what was changed. His court was a mobile affair; he moved constantly from one citadel to another, and distributed his wives and concubines among all of them, so that wherever he went, he could be sure of loving faces, loving arms. And yet something was wrong. Not with his dispositions, nor with his armies, nor with his supply lines, nor with the loyalty of his many towns and districts and tribesmen. What he sensed was little more than a whiff, a twitch, a tingling sensation of danger from some source close to him. Though never once did he associate his premonition with his refusal to appoint Bomilcar regent. "It's in the court," he said to Bomilcar as they rode from Capsa to Cirta at the end of March, walking their horses at the head of a huge train of cavalry and infantry. Bomilcar turned his head and looked straight into his half brother's pale eyes. "The court?" "There's mischief afoot, brother. Sown and cultivated by that slimy little turd Gauda, I'd be willing to bet," said Jugurtha. "Do you mean a palace revolution?" "I'm not sure what I mean. It's just that something is wrong. I can feel it in my bones." "An assassin?" "Perhaps. I really don't honestly know, Bomilcar! My eyes are going in a dozen different directions at once, and my ears feel as if they're rotating, they're so busy yet only my nose has discovered anything wrong. What about you? Do you feel nothing?" he asked, supremely sure of Bomilcar's affection, trust, loyalty. "I have to say I feel nothing," said Bomilcar. Three times did Bomilcar maneuver the unwitting Jugurtha into a trap, and three times did Jugurtha manage to extricate himself unharmed. Without suspecting his half brother. "They're getting too clever," said Jugurtha after the failure of the third Roman ambush. "This is Gaius Marius or Publius Rutilius at work, not Metellus." He grunted. "I have a spy in my camp, Bomilcar." Bomilcar managed to look serene. "I admit the possibility. But who would dare?" "I don't know," said Jugurtha, his face ugly. "But rest assured, sooner or later I will know." At the end of April, Metellus invaded Numidia, persuaded by Rutilius Rufus to content himself at first with a slighter target than the capital, Cirta; the Roman forces marched on Thala instead. A message came from Bomilcar, who had lured Jugurtha in person to Thala, and Metellus made a fourth attempt to capture the King. But as it wasn't in Metellus to go about the storming of Thala with the speed and decision the job needed, Jugurtha escaped, and the assault became a siege. A month later Thala fell, and much to Metellus's gratified surprise, yielded a large hoard of treasure Jugurtha had brought to Thala with him, and had been obliged to leave behind when he fled. As May slid into June, Metellus marched to Cirta, where he received another pleasant surprise. For the Numidian capital surrendered without a fight, its very large complement of Italian and Roman businessmen a significantly pro-Roman force in town politics. Besides which, Cirta did not like Jugurtha any more than he liked Cirta. The weather was hot and very dry, normal for that time of the year; Jugurtha moved out of reach of the slipshod Roman intelligence network by going south to the tents of the Gaetuli, and then to Capsa, homeland of his mother's tribe. A small but heavily fortified mountain citadel in the midst of the Gaetulian remoteness, Capsa contained a large part of Jugurtha's heart, for it was here his mother had actually lived since the death of her husband, Bomilcar's father. And it was here that Jugurtha had stored the bulk of his treasure. It was here in June that Jugurtha's men brought Nabdalsa, caught coming away from Roman-occupied Cirta after Jugurtha's spies in the Roman command finally obtained enough evidence of Nabdalsa's treachery to warrant informing the King. Though always known as Gauda's man, Nabdalsa had not been prevented from moving freely within Numidia; a remote cousin with Masinissa's blood in him, he was tolerated and considered harmless. "But I now have proof," said Jugurtha, "that you have been actively collaborating with the Romans. If the news disappoints me, it's chiefly because you've been fool enough to deal with Metellus rather than Gaius Marius." He studied Nabdalsa, clapped in irons upon capture, and visibly wearing the signs of harsh treatment at the hands of Jugurtha's men. "Of course you're not in this alone," he said thoughtfully. "Who among my barons has conspired with you?" Nabdalsa refused to answer. "Put him to the torture," said Jugurtha indifferently. Torture in Numidia was not sophisticated, though like all Eastern-style despots, Jugurtha did avail himself of dungeons and long-term imprisonment. Into one of Jugurtha's dungeons, buried in the base of the rocky hill on which Capsa perched, and entered only through a warren of tunnels from the palace within the citadel's walls, was Nabdalsa thrown, and there the subhumanly brutish soldiers who always seemed to inherit such positions applied the torture. Not very long afterward, it became obvious why Nabdalsa had chosen to serve the inferior man, Gauda; he talked. All it had taken was the removal of his teeth and the fingernails of one hand. Summoned to hear his confession, the unsuspecting Jugurtha brought Bomilcar with him. Knowing that he would never leave the subterranean world he was about to enter, Bomilcar gazed into the illimitable heights of the rich blue sky, sniffed the sweet desert air, brushed the back of his hand against the silky leaves of a flowering bush. And strove to carry the memories with him into the darkness. The poorly ventilated chamber stank; excrement, vomitus, sweat, blood, stagnant water, and dead tissue clubbed together to form a miasma out of Tartarus, an atmosphere no man could breathe without experiencing fear. Even Jugurtha entered the place with a shiver.

The inquisition proceeded under terrible difficulties, for Nabdalsa's gums continued to bleed profusely, and a broken nose prevented attempts to stanch the haemorrhage by packing the mouth. Stupidity, thought Jugurtha, torn by a mixture of horror at the sight of Nabdalsa and anger at the thoughtlessness of his brutes, beginning in the one place they ought to have kept free and clear of their attentions. Not that it mattered a great deal. Nabdalsa uttered the one vital word on Jugurtha's third question, and it was not too difficult to understand as it was mumbled out through the blood. "Bomilcar." "Leave us," said the King to his brutes, but was prudent enough still to order them to remove Bomilcar's dagger. Alone with the King and the half-conscious Nabdalsa, Bomilcar sighed. "The only thing I regret," he said, "is that this will kill our mother." It was the cleverest thing he could have said under the circumstances, for it earned him a single blow from the executioner's axe instead of the slow, lingering dying his half brother the King yearned to inflict upon him. "Why?" asked Jugurtha. Bomilcar shrugged. "When I grew old enough to start weighing up the years, brother, I discovered how much you had cheated me. You have held me in the same contempt you might have held a pet monkey." "What did you want?" Jugurtha asked. "To hear you call me brother in front of the whole world." Jugurtha stared at him in genuine wonder. "And raise you above your station? My dear Bomilcar, it is the sire who matters, not the dam! Our mother is a Berber woman of the Gaetuli, and not even the daughter of a chief. She has no royal distinction to convey. If I were to call you brother in front of the whole world, all who heard me do so would assume that I was adopting you into Masinissa's line. And that since I have two sons of my own who are legal heirs would be imprudent, to say the very least." "You should have appointed me their guardian and regent," said Bomilcar. "And raise you again above your station? My dear Bomilcar, our mother's blood negates it! Your father was a minor baron, a relative nobody. Where my father was Masinissa's legitimate son. It is from my father I inherit my royalty." "But you're not legitimate, are you?" "I am not. Nevertheless, the blood is there. And blood tells." Bomilcar turned away. "Get it over and done with," he said. "I failed not you, but myself. Reason enough to die. Yet beware, Jugurtha." "Beware? Of what? Assassination attempts? Further treachery, other traitors?" "Of the Romans. They're like the sun and the wind and the rain. In the end they wear everything down to sand." Jugurtha bellowed for the brutes, who came tumbling in ready for anything, only to find nothing untoward, and stood waiting for orders. "Kill them both," said Jugurtha, moving toward the door. "But make it quick. And send me both their heads." The heads of Bomilcar and Nabdalsa were nailed to the battlements of Capsa for all to see. For a head was more than a mere talisman of kingly vengeance upon a traitor; it was fixed in some public place to show the people that the right man had died, and to prevent the appearance of an imposter. Jugurtha told himself he felt no grief, just felt more alone than ever before. It had been a necessary lesson: that a king could trust no man, even his brother. However, the death of Bomilcar had two immediate results. One was that Jugurtha became completely elusive, never staying more than two days in any one place, never informing his guard where he was going next, never allowing his army to know what his plans for it were; authority was vested in the person of the King, no one else. The other result concerned his father-in-law, King Bocchus of Mauretania, who had not actively aided Rome against his daughter's husband, but had not actively aided Jugurtha against Rome either; the feelers went out from Jugurtha to Bocchus at once, and Jugurtha put increased pressure upon Bocchus to ally himself with Numidia, eject Rome from all of Africa.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «1. First Man in Rome» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «1. First Man in Rome» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.