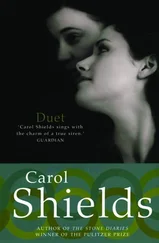

Carol Shields - Unless

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Carol Shields - Unless» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Unless

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Unless: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Unless»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Unless — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Unless», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She, the girl she was two years ago, would be grateful for any scarf I brought her, pleased I had taken the time, but for once I wanted, and had an opportunity to procure, a scarf that would delight her heart.

As I moved from one boutique to the next I began to form a very definite notion of the scarf I wanted for Norah, and began, too, to see how impossible it might be to accomplish this task. The scarf became an idea; it must be brilliant and subdued at the same time, finely made, but with a secure sense of its own shape. A wisp was not what I wanted, not for Norah.

Solidity and presence were what I wanted, but in sinuous, ephemeral form. This was what Norah at seventeen, almost eighteen, was owed. She had always been a bravely undemanding child. Once, when she was four or five, she told me how she controlled her bad dreams at night. “I just turn my head around on the pillow,” she said matter-of-factly, “and that changes the channel.” She performed this act instead of calling out to us or crying; she solved her own nightmares and candidly exposed her original solution — which Tom and I took some comfort in but also, I confess, some amusement. I remember, with shame now, telling this story to friends, over coffee, over dinner, my brave little soldier daughter, controlling her soldierly life.

I seldom wear scarves myself, I can’t be bothered, and besides, whatever I put around my neck takes on the configuration of a Girl Guide kerchief, the knot working its way straight to the throat and the points sticking out rather than draping gracefully downward. I am not clever with accessories, I know that about myself, and I am most definitely not a shopper. Although I possess a faltering faiblesse for luxury, I have never understood what it is that drives other women to feats of shopping perfection, but now I had a suspicion. It was the desire to please someone fully, even oneself. It seemed to me, in that stupidly innocent time, that my daughter Norah’s future happiness now balanced not on acceptance at McGill or the acquisition of a handsome new boyfriend but on the simple ownership of a particular article of apparel, which only I could supply. I had no power over McGill or the boyfriend or, in fact, any real part of her happiness, but I could provide something temporary and necessary: this dream of transformation, this scrap of silk.

And there it was, relaxed over a fat silver hook in what must have been the twentieth shop I entered. The little bell rang; the now-familiar updraft of potpourri rose to my nostrils, and Norah’s scarf flowed into view. It was patterned from end to end with rectangles, each subtly out of alignment: blue, yellow, green, and a kind of pleasing violet. And each of these shapes was outlined by a band of black and coloured in roughly as though with an artist’s brush. I found its shimmer dazzling and its touch icy and sensuous. Sixty American dollars. Was that all? I whipped out my credit card without a thought. My day had been well spent. Then, looking around, I bought crescent-shaped earrings for Natalie, silver, and a triple-beaded bracelet for Christine. I made all these decisions in one minute. I felt full of intoxicating power.

In the morning I took the train to Baltimore. I couldn’t read on the train because of the jolting between one urban landscape and the next. Two men seated in front of me were talking loudly about Christianity, its sad decline, and they ran the words Jesus Christ together as though they were some person’s first and second name — Mr. Christ, Jesus to the intimates.

In Baltimore, once again, there was little for me to do, but since I was going to see Gwen at lunch, I didn’t mind. A young male radio host wearing a black T-shirt and gold chains around his neck asked me how I was going to spend the Offenden Prize money. He also asked what my husband thought of the fact that I’d written a novel. Then I visited the Book Plate (combination café and bookstore) and signed six books, and then, at not quite eleven in the morning, there was nothing more for me to do until it was time to meet Gwen.

I hadn’t seen her since the days of our old writing group back in Orangetown, when we met twice monthly to share and “workshop” our writing. Poetry, memoirs, fiction; we brought photocopies of our work to these morning sessions, where over coffee and muffins — this was the early eighties, the great age of muffin — we kindly encouraged each other and offered tentative suggestions, such as “I think you’re maybe one draft from being finished” or

“Doesn’t character X enter the scene a little too late?” These critical crumbs were taken for what they were, the fumblings of amateurs. But when Gwen spoke we listened. Once she thrilled me by saying of something I’d written, “That’s a fantastic image, that thing about the whalebone. I wish I’d thought of it myself.” Her short stories had actually been published in a number of literary quarterlies, and there had even been one near-mythical sale, years earlier, to Harper’s. When she moved to Baltimore five years ago to become writer-in-residence for a small women’s college, our writers’ group fell first into irregularity and then slowly died away.

We’d kept in touch, though, Gwen and I. I wrote ecstatically when I happened to come across a piece of hers in Three Spoons that was advertised as being part of a novel-in-progress. She’d used my whalebone metaphor; I couldn’t help noticing and, in fact, felt flattered. I knew about that novel of Gwen’s — she’d been working on it for years, trying to bring a feminist structure to what was really a straightforward autobiographical account of an early failed marriage. Gwen had made sacrifices for her young student husband, and he had betrayed her with his infidelities. In the late seventies, in the throes of love and anxious to satisfy his every demand, she had had her navel closed by a plastic surgeon because he complained that it smelled “off.” This complaint, apparently, had been made only once, a sour, momentary whim, but out of some need to please or punish she became a woman without a navel, left with a flattish indentation in the middle of her belly, and this navel-less state, more than anything, became her symbol of regret and anger. She spoke of erasure, how her relationship to her mother — with whom she was on bad terms anyway — had been erased along with the primal mark of connection. She was looking into navel reconstruction, she’d said in her last e-mail, but the cost was criminal. In the meantime, she’d retaken her unmarried name, Reidman, and had gone back to her full name, Gwendolyn.

She’d changed her style of dress too. I noticed that right away when I saw her seated at the Café Pierre. Her jeans and sweater had been traded in for what looked like large folds of unstitched, unstructured cloth, skirts and overskirts and capes and shawls; it was hard to tell precisely what they were. This cloth wrapping, in a salmon colour, extended to her head, completely covering her hair, and I wondered for an awful moment if she’d been ill, undergoing chemotherapy and suffering hair loss. But no, there was her fresh, healthy, rich face. Instead of a purse she had only a lumpy plastic bag with a supermarket logo. That did seem curious, especially because she put it on the table instead of setting it on the floor as I would have expected. It bounced slightly on the sticky wooden surface, and I remembered that she always carried an apple with her, a paperback or two, and her small bottle of cold-sore medication.

Of course I’d written to her when My Thyme Is Up was accepted for publication, and she’d sent back a postcard saying, “Well done, it sounds like a hoot.”

I was a little surprised that she hadn’t brought a copy for me to sign, and wondered at some point, halfway through my oyster stew, if she’d even read it. The college pays her shamefully, and I know she doesn’t have money for new hardcover books. Why hadn’t I had Mr. Scribano send her a complimentary copy?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Unless»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Unless» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Unless» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.