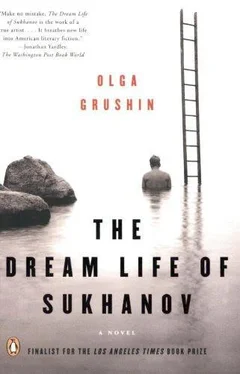

“Nice tie you have there, mister,” the youth said conversationally. “What’s the label?”

Sukhanov swallowed. “What do you mean, ‘label’?”

“I mean, who made it?” the youth said. “It’s got to be written on it.”

Moving slowly as if underwater, Sukhanov lifted his favorite wine-red tie and read in a faltering voice, with a sense of nearing doom, “It’s… er… Christian Dior.”

“How nice for you,” the youth said, clicking his tongue in appreciation.

“Listen, what do you want?” Sukhanov said hoarsely. “Do you want this tie? Take it.”

“Nah, thanks, don’t need it,” said the youth, “not my style. How about two kopecks, though?”

“You want two kopecks?” Sukhanov repeated dully.

The youth nodded, and his eyes darted crazily in his pimpled face. Knowing that something unthinkable was about to befall him, Sukhanov reached a shaking hand into his pocket and held out a few coins. One single thought fluttered in him like a dying moth—why didn’t I take the metro, why didn’t I take the metro, why didn’t I… The bridge was deserted, and he imagined himself flying, falling endlessly through the night, plunging toward a dark, cold death below, and this monster laughing, laughing above him…. The youth bent over his hand, so close that Sukhanov could smell the stale smoke on his breath.

“Let’s see what you have here. Five, ten, another five… Aha, here we go!” He picked a small copper coin from Sukhanov’s palm. “Well, thanks so much, mister. Got to go call my mom now. She always worries when I stay out late.”

And with these words he turned and walked off, back toward Red Square. In an instant the bridge seemed filled with people. Two drunk girls stumbled along, singing over and over, “We wish you happiness,” a line from a popular song; a middle-aged couple passed, arguing about a burnt teakettle; a group of six or seven little Asian men in suits trotted by, carrying a gigantic map of the city unfolded between them, taking countless pictures of the river, chattering in some birdlike tongue. Sukhanov stared about in astonishment, unable to comprehend what had just happened. Then, all at once, he understood, and a wave of laughter washed over him. That boy—that hooligan with the lunatic eyes—had simply needed change for a public phone.

And at that glorious moment of realization, all the misfortunes of the evening turned trivial in Sukhanov’s mind, and even the whole Belkin incident did not matter any longer. The beating of the black wings ceased in his heart. Oh, it was all quite obvious really, not worth another thought. Of course, the man had come for the sole purpose of humiliating him—him, Sukhanov, who had accomplished so much in life! Yes, he had come to fling his success in Sukhanov’s face—but in truth, there was no success, just a measly little show that had arrived a lifetime too late and meant nothing. Still laughing, Sukhanov pulled the invitation out of his pocket. The glossy paper had hardened with dampness, but after a brief struggle he overcame its resistance, ripping it along the middle, then again, then again…. As he threw the pieces over the parapet and watched them spiral down into the lead-colored water, he felt perfectly at peace with himself. One shred fluttered in the air and landed on the railing; he saw three brightly colored letters, blue, indigo, and violet—the very tail of the rainbow. For an instant he looked at the letters with narrowed eyes, then shrugged and sent the shred into the dim, glimmering void with an adroit flick of his finger.

The rest happened with the magic facility of a dream. Immediately as he turned to go, a taxi approached with a welcoming green light burning behind its windshield. Incredibly, it pulled to a stop even before he had time to raise his hand, and then there he was, in the backseat, leaning forward to give the address.

After his brush with death, everything seemed impossibly amusing to him—the quickening flicker of shop signs beyond his window, the cab that, for some unfathomable reason, smelled of violets, the driver whom he could not see clearly in the shadows but whose funny straw-colored beard and old-fashioned glasses leapt in continuous jolts through the rearview mirror, and most of all, the stubborn solemnity with which the man kept assuring him that his street did not exist.

“Belinsky Street?” he was exclaiming. “Believe me, comrade, I know Moscow like my own hand”—every time he said that, he lifted a delicate, childlike hand off the wheel and wiggled his fingers— “and there is no such street anywhere near the Tretyakovskaya Gallery.”

“There most certainly is, I guarantee you,” Sukhanov repeated. “I’ve lived on that street for the past twelve years, so I should know.”

This argument would make the man fall quiet for a minute or two, but invariably he would start again, and his beard’s reflection would flit about in agitation as the darkness inside the taxi breathlessly chased the darkness outside.

“Of course, it’s your business, comrade. If you want to be taken to a place that does not exist, who am I to stop you? Why, I take people places all the time, and half of them end up somewhere they had no intention of going, but me, I never object, I—”

“Turn left here,” Sukhanov interrupted. “The gray building on the right, you see?”

“This?” the driver said triumphantly. “I knew it! This here is no Belinsky Street. This is Voskresensky Passage. Let me back up to the sign and I’ll show you, hold on.”

Sukhanov smiled indulgently. The tires squealed. The square black letters on the white background spelled out “Belinsky Street,” as, naturally, he knew they would. There was a momentary silence, and then a long, sorrowful sigh sounded in the dimness.

“I don’t believe it!” the man wailed softly. “They’ve renamed this one too! And the old name was so much better…. Please accept my apologies. I’ve memorized the whole map of the city, you see, the street names, the intersections, everything, but my map is a bit out of date—it was printed before the Revolution—so this kind of thing is bound to happen from time to time.”

“And does it happen often?” Sukhanov inquired innocently.

The man suppressed a sob. “Almost always,” he confessed in a tragic whisper.

What a loon, thought Sukhanov, as he extracted a ten-ruble bill from his wallet.

“Perhaps you should buy yourself a new map with the change,” he said generously, and chuckling under his breath, stepped out of the car, catching as he did so the last sparkle of the glasses and a farewell wave of the yellow beard bristling on the man’s invisible chin.

Nina was standing in the illuminated doorway, her face tired and pale, her fingers drumming on the doorjamb.

“I saw the taxi from the window,” she said. “I was getting worried—Ksenya and Vasily returned over an hour ago…. Oh, but your jacket is all wet!”

“The rain was nothing,” said Sukhanov nonchalantly. “On the other hand, I did nearly get mugged.”

Nina clutched the golden-edged blue robe at her throat.

“It’s all my fault, isn’t it?” she said. “I should have waited for you in the car.”

A few minutes later Sukhanov, wrapped in a matching red robe, sat in the brightly lit kitchen, under a low-hanging orange lampshade, drinking cognac-laced tea and energetically devouring strawberry preserves. Around him, his family was gathered.

“And then I said to the man, ‘You want my tie, eh? Well, I don’t think so, I’m rather partial to it myself. Here, take these two kopecks instead, that’s all you are good for,”’ Sukhanov was saying with enjoyment between the sweet spoonfuls.

“But Tolya, he could have hurt you!” Nina exclaimed. “What if he had a knife?”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)