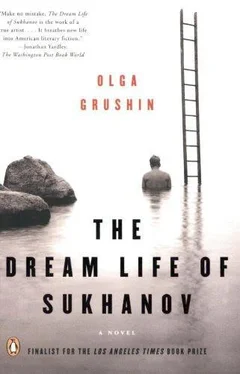

“Of course, I understand,” Belkin said quietly. “Well, good-bye then, Anatoly. Good luck to you and everything.”

He turned up the collar of his burgundy blazer, produced a disheveled umbrella from his pocket (ridiculous, who in the world keeps a wet umbrella in his pocket!), and without another glance stepped into the darkness. Sukhanov noticed that he stooped. Strange, he used to carry himself so straight, he thought involuntarily—and all at once, this stray little thought released in him some echo of the past, a solitary trembling note whose sound rose higher and higher in his chest, awakening inarticulate longings and, inseparable from them, a piercing, unfamiliar sorrow. He watched as Belkin trudged away into the downpour under his lopsided umbrella with one spoke sticking out, and he thought bitterly, Here we are, two aging fools, and our lives almost over. His throat tightened, and for a second he was afraid he would not be able to call out, to say anything at all…. Then the spasm passed.

“Leva, wait!” he shouted.

He feared at first that Belkin had not heard, that the rain had snatched away his words. Then Belkin turned. He was struggling with the umbrella, which had grown unruly.

“Listen, Leva, why did you come here tonight?”

“Oh, I was just passing by when the rain started, and I thought I’d wait it out!” Belkin yelled back.

Sukhanov could not see his eyes—he was too far, it was too dark.

“But… you have an umbrella!” he shouted again.

“Not a very useful one, as you can see.”

“Oh yes, of course, I see! Well, so long now. Say hi to… I mean, take care of yourself!”

Belkin did not move. The umbrella flapped over his head like a demented bird. Several moments passed, dreary, endless as a lifetime. Then he muttered something under his breath and strode back, throwing up sprays of water with each heavy step. His face, as he stopped before Sukhanov, streamed with rain.

“All right, so that wasn’t true,” he said, scowling. “I came because I wanted to see you. You and Nina. I read about the opening, and I thought, What better chance will I have?”

Violently squashing the umbrella, he dropped it at his feet, then fumbled in his sagging pocket. A golden candy wrapper flew out, twirled in the wind, and drowned. Sukhanov observed his movements with strange anticipation. Finally Belkin extracted what looked like a glossy postcard and held it locked between his palms.

“I wanted to give you this,” he said. “It’s next Wednesday. Naturally, it’s not going to be a big deal, nothing to write about in the papers…. Anyway, I realize now it was stupid of me, you can’t possibly be interested, so—”

Wordlessly Sukhanov stretched out a slightly trembling hand. Belkin hesitated, then shrugged, and shoved the postcard at him. A jumble of multicolored letters leapt wildly, confusingly, in all directions, against a shocking neon-green background. Sukhanov took off his glasses, smeared rain all over the lenses, and tried again. The letters started to behave more predictably, and eventually, in a long minute or two, joined to form a few words—“L. B. Belkin (1932—). Moscow Through a Rainbow”—and, underneath, in smaller print, the address, the dates, the times…

And as Sukhanov looked in silence, he knew that his wrenching sorrow was giving way to some other, as yet unnamed, feeling, which was slowly unfurling its black, powerful wings inside his heart.

Belkin began to speak rapidly. “It’s my first, you see. True, I’ve had a few things displayed here and there, but this one, it’s all my own. Just a little gallery in the Arbat, but I’ll have the whole place to myself. The name, of course, is idiotic—it’s so cliché, it wasn’t my idea, but I let them do it, because my work is all about color studies anyway, so I thought… Oh, hell, what am I talking about?” Abruptly he stopped, pressing his fingertips to his temples. Then, in a different voice, quiet and oddly desperate, he said, “Listen, Tolya, I know we didn’t remain friends, but it’s been almost a quarter of a century, and… Well, it would make me really happy if you and Nina could come to the opening. It’s on Wednesday, at seven o‘clock, it’s all written right here, in the corner, see?”

Sukhanov started as if emerging from a trance. He had a broad smile on his face.

“Of course,” he said, twisting the card and smiling, smiling. “That is, I’ll have to check my schedule, but I’ll be glad if I can… Nina too, I’m sure… Most glad…”

Belkin looked at him closely, then averted his eyes.

“It would mean a lot to me,” he said softly “But I’ll understand if you’re busy, I know this is rather short notice…. Please say hi to Nina for me. Good night, Tolya.”

“Good night, Leva,” said Sukhanov, still smiling.

Belkin raised a hand in one last farewell and walked off, grappling with his glistening absurdity of an umbrella. Sukhanov remained where he was, crushing the card in his fingers, smiling the same frozen smile as he gazed into nothingness. In a short while the rain began to diminish, rarefy, slow down, until it reverted to the same innocuous drizzle with which it had started earlier—an hour or an eternity ago, depending on one’s point of view…. Sukhanov blinked, shook the water off his shoes, buried the wet invitation in his pocket, and briskly set off in the opposite direction from the one in which his former best friend had disappeared.

He was halfway across Red Square when it occurred to him that he had forgotten to say congratulations.

The black face of the giant clock on the Spasskaya Tower swam ominously in the floodlit clouds; as its golden hand shivered and leapt to a new notch, the chimes announced a quarter to an hour. It had been years, if not decades, since Sukhanov had last found himself in Red Square so late at night, and the virtually deserted, brightly illuminated expanse made him feel uneasy. The greenish cobblestones, slippery from the rain, glistened coldly, and the cathedral of Vasily Blazhennyi rose before him like a many-headed, iridescent, scaly dragon from some tale with an unhappy ending. A youth in an oversized purple jacket appeared from nowhere and followed him for a while, his steps echoing loudly and menacingly in the surrounding stillness; then, just as abruptly, he was gone. Sukhanov nervously touched the lining of his breast pocket and walked faster. As he neared the end of the square, it seemed to him that someone tittered from the dense shadows. He reached the Bolshoi Moskvoretsky Bridge almost at a run.

There he stopped and leaned against the parapet to catch his breath. His legs were aching. Below, the Moscow River moved its slow, dense, brown waters, and from their depths emerged a flimsy upside-down city that existed only at night, created by a thousand shimmering intertwinings of streetlights, headlights, floodlights. The walls, the churches, the bell towers of the underwater city trembled with a desire to break free, to float away with the current, to leave the oppressing, crowded, dangerous Moscow far, far behind; but the night held them firmly, and they stayed forever tethered to their places by infinite golden chains of reflections. Other things were luckier in their flight—dead branch, a billowing white scarf, a fleet of cigarette butts, a gasoline stain widening in the beam of light… Unable to tear his eyes away, Sukhanov looked at the rainbow-colored film spreading across the water. The invitation burned in his pocket, and that unnameable feeling was beating its great black wings in the hollow of his soul.

Suddenly the sounds of someone running banged along the pavement, growing closer. He swung around. The youth in the purple jacket stood behind him, grinning and breathing noisily. Sukhanov glanced up and down the bridge in desperation, but there was no one, no one at all; only cars flew in and out of the night, too quickly, too quickly… His heart pushed in his throat.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)