He had to name himself: in the past five years we had exchanged only a few static-filled sentences, and I did not recognize his voice.

“Nina’s asleep,” I said curtly—it was only nine o‘clock, but I could see no light under the door to our room.

“Actually, Anatoly,” he said, “I wanted to talk to you. Not on the phone, though. Would you be so kind as to come over? Take a pen, I’ll give you my address.”

“I remember it,” I said, then added pointedly, “I have a very good memory, Pyotr Alekseevich.”

“Indeed?” he said without expression. “Then I’ll see you in half an hour.”

The cold seeped beneath my upturned collar and damp snow slapped my face as I crossed the night between our homes. Although I tried to assure myself that I owed Nina the courtesy of this visit, my mood worsened by the minute. In the lobby I had an altercation with the concierge, who for a long time refused to let me pass; and once I reached Malinin’s landing, still seething from the argument, I was stopped by a middle-aged blonde in a lacy apron who, emerging from the apartment next door, kept talking about some Crimean resort, smiling and pressing a bunch of keys into my hand. Over her shoulder hovered a pimply youth who stared at me with disconcerting curiosity, then exclaimed nonsensically, “I know you, don’t I? You are that mister with the tie, from the Bolshoi Moskvoretsky Bridge, I owe you two kopecks!”—but at that moment Malinin’s lock clicked, and the imposing figure of Nina’s father rose on the doorstep, dressed in a floor-length robe, holding a pear-shaped goblet of cognac in his hand, reflected in the gilded mirrors.

“Please come in,” he said, majestically sweeping his arm inside.

The door closed behind me.

In silence Malinin led me along the corridor. Nothing here had changed in the five years since my first, and last, visit. The Polish officer glared out of his heavy frame at the coat I tossed on the counter and the wet footprints I left on the immaculate floors; the piano, untouched in almost two decades—since Maria Malinina’s premature death—glistened with its dark, useless grandeur in the depths of the drawing room; and through another half-open door I glimpsed, with a sense of oppressive recognition, the crystal chandelier, the mahogany grandfather clock, the crimson velvet curtains—the bourgeois decorations of the scene of my past outburst. No, nothing had changed—and yet, without Nina’s soft domestic presence, the whole place seemed dimmer and dustier and somehow sad; and when, still without speaking, Malinin showed me into the living room, sat me down, poured me a drink, and lowered himself into an armchair across from me, I looked at him closely and suddenly doubted why I was here. I had supposed he had invited me to gloat over my failure; now I was not sure. For a minute we sat uneasily sipping our drinks. Then he cleared his throat.

“I’ll come straight to the point,” he said. “I’ve spoken with your director Penkin, and he is willing to take you back. Naturally, upon certain guarantees.”

“Such as?” Caught by surprise, I sounded sharper than I had intended.

“You understand, of course,” Malinin said coldly, “he can’t afford to damage his reputation by sheltering dubious elements as members of his staff. You must stop dabbling in your underground brand of art, avoid scandalous exhibitions, and stick to painting harvests and whatnot. A few tractors in the wheat ought to make matters right between you. Not unreasonable, under the circumstances, don’t you think? Anatoly?”

When I swirled the cognac in my glass, it gleamed with a rich honey tint, and I thought how much I would love to find the precise color for its luxurious shade. I had planned the second painting in my series in a predominantly yellow palette—the lush saffron of Oriental carpets, the brightness of sunshine on a child’s face, the translucent amber of tea rose petals, the opulent sheen of gold against the cream of a woman’s throat, and perhaps, I realized now, the intoxicating smoothness of liqueurs.

“I had to pull quite a few strings on your behalf,” Malinin’s voice sounded in the distance, “so I would be much obliged if you would at least give me an answer.”

“I’ve quit painting such tripe,” I said indifferently, still studying my glass.

“Oh, have you, now? Must have been recent,” he said.

I shrugged.

“A pity. You weren’t half bad at it, from what I hear…. Excellent, isn’t it? Our ambassador to France dropped it off the other day. A little more, perhaps?… Well, no matter, there are other ways of recommending yourself to your director.” The clock in the next room tried to announce a quarter past the hour, but its valiant rumble was caught and promptly silenced in the folds of the velvet draperies. “How do you feel about criticism, for instance?” Malinin asked. “Simple, respected, and pays well, not to mention the possibilities for advancement. As a matter of fact, let me think—yes, I’ve just agreed to do an article for a good friend of mine. He happens to be the editor of our leading art magazine, Art of the World, I’m certain you’ve read it. I could arrange to add you as my coauthor; he owes me a favor. It would make Penkin happy. Of course, you’d be the one to actually write the text, I’ve never had much liking for this kind of—”

“What’s the article about?” I interrupted.

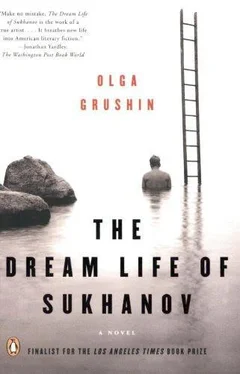

“A subject that you are well familiar with, as I hear from Nina—surrealism. My working title is ‘Surrealism and Other Western “Isms” as Manifestations of Capitalist Insolvency.’ What do you think?”

“I think surrealism is the most brilliant movement of the twentieth century,” I said. “In fact, I myself painted in the surrealist manner for almost two years, and even now, much of my inspiration comes from—”

“Good, good,” said Malinin, standing up and walking to a bookcase. “Then it should be easy for you. Meaningless subjects, amoral disregard of communal values, decadent neglect of reality, nightmares depriving man of joy, that kind of thing…. Here, you can borrow this volume of reproductions, it should help you find all the indignant epithets you need. Would a month be long enough? The issue goes to print in January.”

I flipped through the book he had handed me. It was in English; the pages were bright and glossy, and smelled of new print. I saw a nude with roses blossoming in her belly, a jungle metamorphosing into the ruins of a many-columned city, a bleeding classical bust…

“What you are suggesting,” I said, pushing the volume aside, “is nothing but betrayal—of myself, of my friends, of everything I hold true.”

He smiled unpleasantly.

“Such lofty words,” he said. “How old are you now, Anatoly—thirty-one? Thirty-two?”

“Thirty-three,” I said. “The age of Christ.”

He paused in the process of pouring himself another splash, looked back at me with a raised eyebrow, and I instantly regretted my words. The drink was stronger than I had thought. Wondering hazily whether I had eaten that day—I could not remember—I watched him push the cork back into the ornate bottle.

“Is that really how you see yourself?” he said, seating himself, sweeping the folds of his robe off the floor in the grand gesture of an old Russian aristocrat. “A martyr about to make a great sacrifice? Except that Christ sacrificed himself for the people. For what would you sacrifice yourself—and not just yourself, may I remind you, but your mother and your wife as well? For some vague notion of Art with a capital A? Because let me tell you, Anatoly, the Russian people do not need you and your art. No matter how hard you beat your head against the wall—you and that woebegone friend of yours, what’s his name, Rifkin, Semkin, Bulkin?—along with all the rest of those fellows, no matter how much any of you suffers, no one will ever want to exhibit a single work of yours in this country. My kind of art is what our people love. It may not be as amusing as some fantasy by Chagall, but when millions of tired, unhappy men and women want to find a bit of light, hope, or encouragement at the end of their hard day, they would rather look at paintings of the heroic past and the harmonious future than puzzle over some portrait of a man with an upside-down green face. Why, I can’t tell you how many times—”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)