“Glad?” Lev shouted.

“You bet!” I shouted back.

“Nervous?” Lev said, closer now.

“Not a bit,” I replied, picking up my load. “I have a feeling it will all go splendidly.”

Together we entered the Manège.

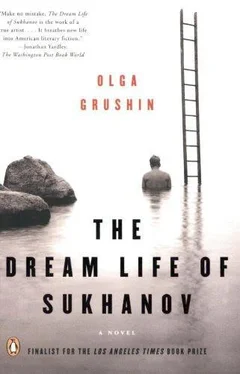

It was the last day of November in the year 1962, and I already imagined it emblazoned on my future memory as the date on which my prolonged apprenticeship was finally destined to end, and to the sonorous cymbals of public acclaim, my heart trembling with gladness, I, Anatoly Sukhanov, a name among names, would enter the gladiators’ ring of art history, stepping into the long-awaited spotlight out of the dim shadows of anonymous toil.

I had lived in anticipation of this day for a long time. The thaw whose first astonishing inroads into the snowdrifts we had witnessed in 1956 was melting its way through history and literature, but had barely made itself felt in the arctic bleakness of Soviet art; and even though for me the preceding years had been rich with that indescribable richness of small-scale triumphs that only an artist knows in his sweaty task of creation, yet little by little my inability to share my canvases with anyone but a handful of close friends, my struggle to maintain my precarious position at the institute, the precautions I continued to take in order to conceal my real self from colleagues and chance acquaintances, the effort of teaching what I no longer believed in—in short, the pervasive duplicity of my existence—poisoned my joy in living, my joy in working, my very desire to paint; and with fading hope, I dreamt of a day when I would tear away the suffocating shroud of falsity and show them, show them all, the ripened fruits of all those years.

And then, unexpectedly, magically, the day came, at the end of a particularly trying month in a trying year, shortly after Nina’s thirtieth birthday.

Nina still tried to pretend, to herself as much as to me, that she was the same girl who one day in 1957 had left her home, breaking with her father, forsaking her old life, and had stood next to me, wearing that white, narrow-waisted dress I liked so much, her back straight, her smile proud, her eyes shining, while an officious woman with thick ankles had monotonously recited solemn commonplaces from a worn compendium of Soviet marriage transactions and Lev’s Alla had giggled into a bunch of wilting gladioli; but even though she continued to call herself the “high priestess” of my art and uncomplainingly slipped away to the kitchen to give me space to work, I could sense the beginning of a change, an insidious, stealthy, corrosive change, in the air between us.

On the evening of November third, the day she turned thirty, she came home from her job at the Tretyakovka wearing that slightly pinched expression I had been noticing of late, and when I unveiled her present—a portrait of her as a mermaid I had worked on in secret, to surprise her—she smiled with her lips only and said in a toneless voice, “Oh. Another painting.” Then she left for a dinner party at her father’s (after years of stubborn resentment, he had offered her a semblance of peace, which failed to include me). I was still up, waiting for her, when she returned, well after midnight. Her face, as she walked in, arrested me, so uncommonly animated it was, and more beautiful than I had seen it in months: her cheeks flushed, I imagined with compliments and expensive liqueurs, her gaze brightened, perhaps with golden memories of her fairy-tale youth; but my impulse to tenderly tilt her head back, look into her eyes, salvage at least something of our day together died a hurried death when I noticed a peacock-blue scintillation following her passage through the shadows of our crowded room. She was wearing a pair of sapphire earrings, and it was they, nothing else, that lent a deep blue brilliance to her gray irises and suffused her pallid skin with an excited warmth.

“What are these?” I asked sharply, knowing the answer already.

“A gift from my father.”

“We can’t accept such things from that man.”

“He is my father,” she said. “He loves me. He wanted to do something nice for my birthday. And you…” She stopped, looked away. “You don’t know anything about him.”

I had the impression she had meant to say something else but changed her mind.

“I know enough,” I said. “I know what he is. I know what he does—bargains away his dignity piece by piece to the highest bidder, paints trash so he can have his cushy life—”

“You paint trash too,” she interrupted. “Your studio at the institute—”

My breath caught. “I paint trash so I can do this,” I said, shoving my chin at the dusty deposits of canvases in the corners, no longer bothering to keep my voice down. “What I do at the institute is irrelevant—this is who I really am.”

“And how do you know who my father really is?”

“Oh, I see—after a day of prostituting himself, he plays the violin or something?”

“Have you ever considered, Tolya,” said Nina slowly, “that you may actually be wrong about something or someone? You think my father is an amoral, selfish man, but maybe…” She paused. “Maybe he just wanted to make me and my mother happy.”

Again I had the feeling that some other, harsher words had alighted on her lips, then been discarded—and it was these unspoken reproaches and accusations, combined with her unnatural calm, that sent a wave of fury crashing over me.

“Well, how noble of him,” I shouted. “He sold his soul to the devil so you could have your jewelry, and your mother her piano and her gilded teacups!”

I regretted my words as soon as they had escaped me, but it was too late. Nina’s face, now drawn and pale in the yellow glow of a bedside lamp, seemed suspended between expressions; then she walked to the window and, staring out into the dreary darkness punctuated by anemic streetlamps, carefully removed the earrings, balanced their tiny blue radiance on her palm, and considered them briefly before setting them down on the windowsill. When she faced me, her eyes held no love, no emotion at all.

“So my mother collected porcelain and was passionate about music,” she said softly. “Is it so wrong to want to have beauty in your life? Not everyone is willing to live… to live like this. And is it really so contemptible to want to give beauty to someone you love?”

Then, not waiting for my answer, she turned and, usually private to a fault, started to undress as if I were not there. In silence I watched her step out of the sea-colored dress her father had brought her years earlier from a trip to Italy, which she still wore on every birthday and New Year’s Eve, gently smooth its creases before hanging it in our makeshift wardrobe, then take off her stockings and, sliding her hand inside, raise them against the light and in a seemingly familiar, tired ritual check for fresh runs. As I looked at the silky shimmer spread between her fingers, I thought mechanically that stockings were very hard to come by nowadays; and on the heels of that thought, the famous words of Chekhov popped into my mind: “A human being should be entirely beautiful: the face, the clothes, the soul, and the thoughts.” And suddenly I was frightened—frightened that something irreparable had happened between us. I thought of the squalor of our dingy place, which had more space for paintings than for us; and the stairs that always reeked of urine; and the anxious hovering of my mother, who kept imagining footsteps outside our door and strange clicks on our phone line, and who, in truth, did not like Nina very much and referred to her, with pursed lips and barely out of earshot—for our communal quarters were too cramped for secrets—as “your fine lady”; I thought too that none of it was ever likely to change.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)