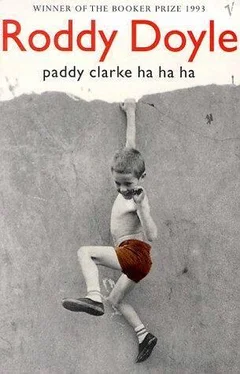

Roddy Doyle - Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Roddy Doyle - Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The 1993 Booker Prize-winner. Paddy Clarke, a ten-year-old Dubliner, describes his world, a place full of warmth, cruelty, love, sardines and slaps across the face. He's confused; he sees everything but he understands less and less.

Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

– Sinbad.

I stood up out of the bed. I was in charge again.

– Sinbad.

I was going to the toilet but I didn’t have to hurry now.

– I’m going to strangle you, I said.

I went to the door.

– But first I’m going to the toilet. There’s no escape.

I wiped the seat. The bathroom light was off but I’d heard the wee smashing on the plastic. I wiped all around and threw the paper into the toilet. Then I flushed it. I got back into the bedroom without touching the door. I crept to his bed but I made one step heavier.

– Francis.

I was giving him one more chance.

– Move over.

It was even: we’d scared each other. There was no noise; he wasn’t moving. I got right up to his bed.

– Move over.

It wasn’t an order; I said it nice.

He was asleep. I could hear it. I hadn’t scared him enough to make him keep awake. I sat on the bed and lifted my feet.

– Francis -

There wasn’t room. I didn’t push him. He was much heavier when he was asleep. I didn’t want to wake him. I went over to my own bed. There was still some warm left. The sheet hole was bigger, too big. My foot got caught in it. I was afraid I’d rip it more.

I was going to sleep. I knew I’d be able to. In the morning I’d tell Sinbad that I hadn’t woken him up.

I listened.

Nothing, then they were talking. Her, him, her, him for longer, her, him long again, her for a bit, him. It was only talking, normal talk. Him talking to her. Man and wife. Mister and Missis Clarke. My eyes had closed by themselves. I stopped listening. I practised my breathing.

– I didn’t wake you up, I told him.

He was ahead of me. It was going all wrong.

– I could have, I told him.

He didn’t care; he’d been asleep. He didn’t believe me.

– But I didn’t.

We’d be at the school soon and we couldn’t be together there. I made myself get up beside him, and then in front. He didn’t look at me. I got in his way. I spoke when he was going around me.

– He hates her.

He kept going, wide enough for me not to grab him, the same speed.

– He does.

We were into the field in front of the school. The grass was long where there were no foundations yet but there were paths worn through the grass and they all joined one path at the end of the field right opposite the school. It was all hay grass in the middle, and nettles and devil’s bread and stickybacks where the ditches were left.

– You don’t have to believe me if you don’t want to, I said. -It’s true though.

That was all. There were piles of boys coming through the field, joining up on the big path. Three fellas from the scholarship class were sitting having a smoke in the wet long grass. One of them was pulling the hay off the grass and spilling it into his lunch box. I went slower. Sinbad got past some fellas and I couldn’t see him any more. I waited for James O’Keefe to catch up.

– Did you do the eccer? he said.

It was a stupid question; we all did the eccer.

– Yeah, I said.

– All of it?

– Yeah.

– I didn’t, he said.

He always said that.

– I didn’t do some of the learning, I said.

– That’s nothing, he said.

The eccer was always corrected, all of it. We could never get away with anything. We had to swap copies; Henno walked around giving the answers and looking over our shoulders. He spot-checked.

– I’m analysing your writing, Patrick Clarke. Tell me why.

– So I won’t write in any of the answers for him, Sir.

– Correct, he said. -And he won’t write in any for you.

He thumped me hard on the shoulder, probably because he’d been nice to me a few days before. It hurt but I didn’t rub it.

– I went to school once myself, he said. -I know all the tricks. Next one: eleven times ten divided by five. First step, Mister O’Keefe.

– Twenty-two, Sir. -First step.

He got James O’Keefe in the shoulder.

– Multiply eleven and ten, Sir.

– Correct. And?

– That’s all, Sir.

He got another whack.

– The answer, you amadán. [21]

– One hundred and ten, Sir.

– One hundred and ten. Is he correct, Mister Cassidy?

– Yes, Sir.

– For once, yes. Second step?

Miss Watkins had been much easier. We always did some of the homework but it was easy to fill in the answers when we were supposed to be correcting the ones we’d already done. Henno made us do the corrections with a red colouring pencil. You got three biffs if the point wasn’t sharp. Twice a week, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, we were allowed, two by two, to go up to the bin beside his desk and sharpen them. He had a parer screwed to the side of the desk – you put the pencil in the hole and turned the handle – but he wouldn’t let us use it. We had to have our own. Two biffs if you forgot to bring it in, and it couldn’t be a Hector Grey’s one, Mickey Mouse or one of the Seven Dwarfs or any of them; it had to be an ordinary one. Miss Watkins always used to write the answers on the board before nine o’clock and then she’d sit behind her desk and knit.

– Hands up who got it right? Go maith . [22]Next one, read it for me, em -

Without looking up from her knitting.

– Patrick Clarke.

I read it off the board and wrote it down in the space I’d left for it. Once, she stood up and came around the desks and stopped and looked at my page; the ink was still wet and she didn’t notice.

– Nine out of ten, she said. - Go maith .

I always made one of them wrong, sometimes two. We all did, except Kevin. He always got ten out of ten, in everything. A great little Irishman, she called him. Kevin did Ian McEvoy in the yard when Ian McEvoy called him that; he gave him a loaf in the nose.

She’d thought she was nice but we’d hated her.

– Still awake, Mister Clarke?

They all laughed. They were supposed to.

– Yes, Sir.

I smiled. They laughed again, not as much as the first time.

– Good, said Henno. -What time is it, Mister McEvoy?

– Don’t know, Sir.

– Can’t afford a watch.

We laughed.

– Mister Whelan.

Seán Whelan lifted the sleeve of his jumper and looked under.

– Half-ten, Sir.

– Exactly?

– Nearly.

– Exactly, please.

– Twenty-nine past ten, Sir.

– What day is it, Mister O’Connell?

– Thursday, Sir.

– Are you sure?

– Yes, Sir.

We laughed.

– It is Wednesday, I’m told, said Henno. And it is half past ten. What book will we now take out of our málas [23], Mister – Mister – Mister O’Keefe?

We laughed. We had to.

I went to bed. He hadn’t come home. I kissed my ma.

– Night night, she said.

– Good night, I said.

There was a hair growing out of a small thing on her face. Just between her eye and her ear. I’d never seen it before, the hair. It was straight and strong.

I woke up. It was just before she’d come up to get us out of bed. I could tell from the downstairs noises. Sinbad was still asleep. I didn’t wait. I got up. I was wide awake. I dashed into my clothes. It was good; the curtain square was bright.

– I was just coming up, she said when I got into the kitchen.

She was feeding the girls, feeding one and making sure that the other one fed herself properly. Catherine often missed her mouth with the spoon. Her bowl was always empty but she never ate that much.

– I’m up, I said.

– So I see, she said.

I was looking at her feeding Deirdre. She never got bored with it.

– Francis is still asleep, I said.

– No harm, she said.

– He’s snoring, I said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Paddy Clarke, Ha Ha Ha» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.