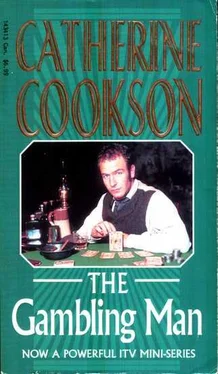

‘I . . . I can’t go there.’

‘But why, Rory? He’s . . . he’s your friend. And if you had seen him in the court that day, why . . .’

Again he was shaking his head. His eyes, screwed up tightly now, were lost in the discoloured puffed flesh.

She sat back and stared at him in deep sadness. She couldn’t understand it. She knew he wasn’t himself yet, but that he wouldn’t make an effort to go and see John George, and him shut up in that place . . . well, she just couldn’t understand it.

When he looked at her again and saw the expression on her face, he said through clenched teeth, ‘Don’t keep on, Janie. I’m sorry but . . . but I can’t. You know I’ve always had a horror of them places, You know how I can’t stand being shut in, the doors and things. I’d be feared of making a fool of meself. You know?’

The last two words were a plea and although in a small way she understood his fear of being shut in, she thought that he might have tried to overcome it for this once, just to see John George and ease his plight.

She said softly, ‘Somebody should go; he’s got nobody, nobody in the world.’

He muttered something now and she said, ‘What?’

‘You go.’

‘Me! On me own, all that way? I’ve never been in a train in me life, and never on the ferry alone, I haven’t.’

‘Take one of them with you.’ He motioned his head towards the scullery. And now she nodded at him and said, ‘Aye, yes, I could do that. I’ll ask them.’ She stared at him a full minute before she rose from the chair and went into the scullery.

Both Lizzie and Ruth turned towards her and waited for her to speak. She looked from one to the other and said, ‘He won’t, I mean he can’t come up to Durham with me to see John George, he doesn’t feel up to it . . . not yet. If it had been later. But . . . but it’s early days you know.’ She nodded at them, then added, ‘Would one of you?’

Ruth looked at her sadly and said, ‘I couldn’t, lass, I couldn’t leave the house an’ him an’ them all to see to. Now Lizzie here—’

‘What! me? God Almighty! Ruth, me go to Durham! I’ve never been as far as Shields Market in ten years. As for going on a train I wouldn’t trust me life in one of ’em. And another thing, lass.’ Her voice dropped. ‘I haven’t got the proper clothes for a journey.’

‘They’re all right, Lizzie, the ones you’ve got. There’s your good shawl. You could put it round your shoulders. An’ Ruth would lend you her bonnet, wouldn’t you, Ruth?’

‘Oh, she could have me bonnet, and me coat an’ all, but it wouldn’t fit her. But go on, it’ll do you good.’ She was nodding at Lizzie now. ‘You’ve hardly been across the doors except to the hospital—’ she paused but didn’t add, ‘since you came from over the water’ but said ‘in years. It’s an awful place to have to be goin’ to but the journey would be like a holiday for you.’

‘I’d like to see John George.’ Lizzie s voice was quiet now. ‘Poor lad. A fool to himself, always was. He used to slip me a copper on a Sunday even though I knew he hadn’t two pennies to rub against one another. And I didn’t want to take it, but if I didn’t he’d leave it there.’ She pointed to the corner of the little window-sill. ‘He’d drop it in the tin pot. The Sunday there wasn’t tuppence in there I knew that his funds were low indeed. Aye, lass, I’ll come along o’ you. I’ll likely look a sketch an’ put you to shame, but if you don’t mind, I don’t, lass.’

Janie now laughed as she put out her hand towards Lizzie and said, ‘I wouldn’t mind bein’ seen with you in your shift, Lizzie,’ and Ruth said, ‘Oh! Janie, Janie,’ and Lizzie said, ‘You’re a good lass, Janie. You’ve got what money can’t buy, a heart. Aye, you have that.’

It took some minutes before Janie could speak to John George. It was Lizzie who spoke first. ‘Hello there, lad,’ she said, and he answered, ‘Hello, Lizzie. Oh hello, Lizzie,’ in just such a tone as he would have used when holding out his hands towards her. But there was the grid between them.

‘Hello, Janie.’

There was a great hard lump in her throat. The tears were blinding her but through them the blurred outline of his haggard features tore at her heart. ‘How . . . how are you, John George?’

‘Well . . . well, you know, Janie, not too bad, not too bad. Rough with the smooth, Janie, you know. Rough with the smooth. How . . . how is everybody back there?’

‘All right. All right, John George. Rory, he . . . he couldn’t make it, John George, he’s still shaky on his legs after the knockin’ about, like they told you. Eeh! he was knocked about, we never thought he’d live. He would have been here else. He’ll come later, next time.’

John George made no reply to Janie’s mumbled discourse but he looked towards Lizzie and she, nodding at him, added, ‘Aye, he’ll come along later. He sent his regards.’

‘Did he?’ He was addressing Janie again.

‘Aye.’

‘What did he say, Janie?’

‘What was that, John George?’

He leant farther towards the grid. ‘I said what did Rory say?’

‘Oh, well.’ She sniffed, then wiped her eyes with her handkerchief before mumbling, ‘He said to keep your pecker up an’ . . . an’ everything would work out once you get back.’

‘He said that?’ He was holding her gaze and she didn’t reply immediately, so that when she did say ‘Aye,’ it carried no conviction to him.

‘We’ve brought you a fadge of new bread an’ odds an’ ends.’ Lizzie now pointed to the parcel and he said, ‘Oh, ta, Lizzie. It’s kind of you; you’re always kind.’

‘Ah, lad, talkin’ of being kind, that’s what’s put you here the day, being kind. Aw, lad.’

They both looked at the bent head now; then when it jerked up sharply they were startled by the vehemence of his next words. ‘I didn’t take five pounds, I didn’t! Believe me. Will you believe me?’ He was staring now at Janie. ‘I did take the ten bob. As I said, I’d done it afore but managed to put it back on the Monday morning, you know after going to the pawn.’ He glanced towards Lizzie now as if she would understand the latter bit. Then looking at Janie again, he said, ‘Tell him, will you? Say to him, John George said he didn’t take the five pounds. Will you, Janie?’

It was some seconds before she answered, ‘Aye. Yes, I will. Don’t upset yourself, John George. Yes, I will, an’ he’ll believe you. Rory’ll believe you.’

His eyes were staring into hers and his lips moved soundlessly for a moment before he brought out, ‘Did you go and see Maggie, Janie?’

Janie, flustered now, said, ‘Why, no; I couldn’t, John George, ’cos you didn’t tell me where she lived.’ Just as he put his doubled fist to his brow and bowed his head a bell rang, and as if he had been progged by something sharp he rose quickly to his feet, then gabbled, ‘Horsley Terrace . . . twenty-four. Go, will you Janie?’

‘Yes, John George. Yes, John George.’ They were both on their feet now.

‘Ta, thanks. Thank you both. I’ll never forget you. Will you come again? . . . Come again, will you?’

They watched him form into a line with the others before they turned away.

Outside the gates they didn’t look at each other or speak, and when Lizzie, after crossing the road, leaned against the wall of a cottage and buried her face in her hands Janie, crying again, put her arms about her and having turned her from the wall, led her along the street and into the town. And still neither of them spoke.

Rory stood before the desk and looked down at Charlotte Kean and said, ‘I’m sorry to hear about your father.’

Читать дальше

![Дэвид Балдаччи - A Gambling Man [calibre]](/books/384314/devid-baldachchi-a-gambling-man-calibre-thumb.webp)