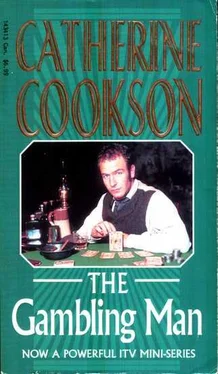

THE GAMBLING MAN

Catherine Cookson

THE CONNORS

Paddy Connor a steelworker

Ruth Connor his wife

Rory Connor their elder son, a rent collector

Jimmy Connor their younger son, apprenticed to a boat builder

Nelly Burke their only daughter, married to Charlie Burke

Lizzie O’Dowd Paddy Connor’s half-cousin

THE WAGGETTS

Bill Waggett a widowed docker

Janie Waggett his daughter, a nursemaid and engaged to marry Rory Connor

Gran Waggett his mother

THE LEARYS

Collum Leary a coal miner

Kathleen Leary his wife

Nine surviving children of whom three have emigrated to America

John George Armstrong Rory’s friend and fellow rent collector

Septimus Kean a property owner

Charlotte Kean his only daughter

PART ONE

1875 Rory Connor

Tyne Dock was deserted. It was Sunday and the hour when the long dusk was ending and the night beginning. Moreover, it was bitterly cold and the first flakes of snow were falling at spaced intervals, dropping to rest in their white purity on the greasy, coal-dust, spit-smeared flags.

The five arches leading from the dock gates towards the Jarrow Road showed streaks of dull green water running down from their domes. Beneath the arches the silence and desolation of the docks was intensified; they, too, seemed to be resting, drawing breath as it were, before taking again the weight of the wagons which, with the dawn, would rumble over four of them from the coal staithes that lay beyond the brick wall linking them together. Beyond the fifth arch the road divided, one section mounting to Simonside, the other leading to Jarrow.

The road to Jarrow was a grim road, a desolate road, and a stretch of it bordered the slakes at East Jarrow, the great open stretch of mud which in turn bordered the river Tyne.

There was nothing grim about the road to Simonside, for as soon as you mounted the bank Tyne Dock and East Jarrow were forgotten, and you were in the country. Up and up the hill you went and there to the left, lying back in their well-tended gardens, were large houses; past the farm, and now you were among green fields and open land as far as the eye could see. Of course, if you looked back you would glimpse the masts of the ships lying all along the river, but looking ahead even in the falling twilight you knew this was a pleasant place, a place different from Tyne Dock, or East Jarrow, or Jarrow itself; this was the country. The road, like any country road, was rough, and the farther you walked along it the narrower it became until finally petering out into a mere cart track running between fields.

Strangers were always surprised when, walking along this track, they came upon the cottages. There were three cottages, but they were approached by a single gate leading from the track and bordered on each side by an untidy tangled hedge of hawthorn and bramble.

The cottages lay in a slight hollow about twenty feet from the gate, and half this distance was covered by a brick path which then divided into three uneven parts, each leading to a cottage door. The cottages were numbered 1, 2 and 3 but were always called No. 1 The Cottages, No. 2 The Cottages, and No. 3 The Cottages.

In No. 1 lived the Waggetts, in No. 2 the Connors, and in No. 3 the Learys. But, as this was Sunday, all the Waggett family and three of the Learys were in the Connors’ cottage, and they were playing cards.

‘In the name of God, did you ever see the likes! He’s won again. How much is it I owe you this time?’

‘Twelve and fourpence.’

‘Twelve an’ fourpence! Will you have it now or will you wait till ye get it?’

‘I’ll wait till I get it.’

‘Ta, you’ve got a kind heart. Although you’re a rent man you’ve got a kind heart. I’ll say that for you, Rory.’

‘Ah, shut up Bill. Are you goin’ to have another game?’

‘No, begod! I’m not. I’ve only half a dozen monkey nuts left, an’ Janie there loves monkey nuts. Don’t you, lass?’

Bill Waggett turned round from the table and looked towards his only daughter, who was sitting with the women who were gathered to one side of the fire cutting clippings for a mat, and Janie laughed back at him, saying, ‘Aw, let him have the monkey nuts; ’cos if you don’t, he’ll have your shirt.’ She now exchanged a deep knowing look with Rory Connor, who had half turned from the table, and when he said, ‘Do you want me to come there and skelp your lug?’ she tossed her head and cried back at him, try it on, lad. Try it on.’ And all those about the fire laughed as if she had said something extremely witty.

Her grannie laughed, her wrinkled lips drawn back from her toothless gums, her mouth wide and her tongue flicking in and out with the action of the aged; she laughed as she said, ‘That’s it. That’s it. Start the way you mean to go on. Married sixty-five years me afore he went; never lifted a hand to me; didn’t get the chance.’ The cavity of her mouth became wider.

Ruth Connor laughed, but hers was a quiet, subdued sound that seemed to suit her small, thin body and her pointed face and black hair combed back from the middle parting over each side of her head.

Her daughter, Nellie, laughed. Nellie had been married for three years and her name now was Mrs Burke. Nellie, like her mother, was small and thin but her hair was fair. The word puny would describe her whole appearance.

And Lizzie O’Dowd laughed. Lizzie O’Dowd was of the Connor family. She was Paddy Connor’s half-cousin. She was now forty-one years old but had lived with them since she had come over from Ireland at the age of seventeen. Lizzie’s laugh was big, deep and hearty; her body was fat, her hair brown and thick; her eyes brown and round. Lizzie O’Dowd looked entirely different from the rest of the women seated near the fire, particularly the last, who was Kathleen Leary from No. 3 The Cottages. Kathleen’s laugh had a weary sound. Perhaps it was because after bearing sixteen children her body was tired. It was no consolation that seven were dead and the eldest three in America for she still had six at home and the youngest was but two years old.

It was now Paddy Connor, Rory’s father, who said, ‘You were talkin’ of another game, lad. Well then, come on, get on with it.’

Paddy was a steelworker in Palmer’s shipyard in Jarrow. For the past fifteen years he had worked in the blast furnaces, and every inch of skin on his face was red, a dull red, like overcooked beetroot. He had three children, Rory being the eldest was twenty-three.

Rory was taller than his father. He was thickset with a head that inclined to be square. He did not take after either his mother or his father in looks for his hair was a dark brown and his skin, although thick of texture, was fresh looking. His eyes, too, were brown but of a much deeper tone than his hair. His lips were not full as might have been expected to go with the shape of his face but were thin and wide. Even in his shirt sleeves he looked smart, and cleaner than the rest of the men seated around the table.

Jimmy, the younger son, had fair hair that sprang like fine silk from double crowns on his head. His face had the young look of a boy of fourteen yet he was nineteen years old. His skin was as fair as his hair and his grey eyes seemed over-big for his face. His body looked straight and well formed, until he stood up, and then you saw that his legs were badly bowed, so much so that he was known as Bandy Connor.

Paddy’s third child was Nellie, Mrs Burke, who was next in age to Rory.

Bill Waggett from No. 1 The Cottages, the son of Gran Waggett and the father of Janie, worked in the docks. He was fifty years old but could have been taken for sixty. His wife had died six years before, bearing her seventh child. Janie was the only one they had managed to rear and he adored her.

Читать дальше

![Дэвид Балдаччи - A Gambling Man [calibre]](/books/384314/devid-baldachchi-a-gambling-man-calibre-thumb.webp)