The following summer Buster came home from school, having completed the eighth grade. Mom and Dad talked about him going on to high school one day when they could afford it, but eighth grade was all the learning lots of folks figured they needed out west-it was more than most got-and Buster wasn’t interested in high school. He knew enough math and reading and writing to run a ranch, and he didn’t see much point in picking up more knowledge than that. Cluttered the mind, in his view.

Not long after Buster got back, it became clear to me that he and Dorothy were sweet on each other. In some ways it was a strange match, since she was a few years older and he scarcely had hair on his chin. Mom was horrified when she found out, but I thought Buster was lucky. He was always a little unmotivated, and if he was going to run the ranch with any success, he’d need someone determined and hardworking like Dorothy beside him.

One day in July, I rode Patches into Tinnie to pick up some dry goods and collect the mail. To my surprise, there was a letter for me, practically the only letter I’d ever received. It was from Mother Albertina, and I sat right down on the steps outside the general store to read it.

She continued to think about me, she wrote, and continued to believe I’d make an excellent teacher. In fact, she went on, she thought I knew enough right now to be a teacher, and that was why she was writing. Because of the war that had started up in Europe, there was a shortage of teachers, particularly in the remote parts of the country, and if I was able to pass a test the government was giving in Santa Fe-it was not an easy test, she warned, the math was particularly tough-I could probably get a job even without a degree and even though I was just fifteen years old.

I was so excited, I had to resist the urge to gallop all the way back to the ranch, but I held Patches at a steady trot, and as I rode along, I kept thinking this was the door Mother Albertina had told me about.

Mom and Dad didn’t like the idea at all. Mom kept saying I had a better chance of marriage if I stayed here in the valley, where I was known as the daughter of a substantial property owner. Off on my own, I’d have less to offer in the way of family and connections. Dad kept throwing out one reason after another: I was too young to be on my own, it was too dangerous, training horses was more fun than drilling illiterate kids in their ABCs, why would I want to be cooped up in a classroom when I could be out on the range?

Finally, after raising all these objections, Dad sat me down on the back porch. “The fact is,” he said, “I need you.”

I had seen that coming. “This’ll never be my ranch, it’s going to Buster, and with Buster marrying Dorothy, you have all the help you need.”

Dad looked out at the horizon. The rangeland rolling toward it was particularly green from a recent rainfall.

“Dad, I got to strike out on my own sometime. Like you’re always saying, I’ve got to find my Purpose.”

Dad thought about it for a minute. “Well, hell,” he said at last. “I suppose you could at least go and take the damn test.”

THE TEST WAS EASIERthan I expected, mostly questions about word definitions, fractions, and American history. A few weeks later, I was back at the ranch when Buster came into the house with a letter for me he’d picked up at the post office. Dad, Mom, and Helen were all there, and they watched me open it.

I’d passed the test. I was being offered the job of an itinerant replacement teacher in northern Arizona. I gave a shriek of delight and started dancing around the room, waving the letter and whooping.

“Oh my,” Mom said.

Buster and Helen were hugging me, and then I turned to Dad.

“Seems you been dealt a card,” Dad said. “I guess you better go on and play it.”

The school that was expecting me was in Red Lake, Arizona, five hundred miles to the west, and the only way for me to get there was on Patches. I decided to travel light, bringing only a toothbrush, a change of underwear, a presentable dress, a comb, a canteen, and my bedroll. I had money from those race purses I’d won, and I could buy provisions along the way, since most every town in New Mexico and Arizona was about a day’s ride from the next.

I figured the trip would take a good four weeks, since I could average about twenty-five miles a day and would need to give Patches a day off every now and again. The key to the trip was keeping my horse sound.

Mom was worried sick about a fifteen-year-old girl traveling alone through the desert, but I was tall for my age, and strong-boned, and I told her I’d keep my hair under my hat and my voice low. For insurance, Dad gave me a pearl-handled six-shooter, but the fact of the matter was, the journey seemed like no big deal, just a five-hundred-mile version of the six-mile ride into Tinnie. Anyway, you had to do what you had to do.

* * *

Patches and I left at first light one morning in early August. Dorothy came up to the house to make me johnnycakes for breakfast and wrapped a few extras in waxed paper for me to carry along. Mom, Dad, Buster, and Helen were all up, and we sat down at the long wooden table in the kitchen, passing the platter of johnnycakes and the tin teapot back and forth.

“Will we ever see you again?” Helen asked.

“Sure,” I said.

“When?”

I hadn’t thought about that, and I realized I didn’t want to think about it. “I don’t know,” I said.

“She’ll be back,” Dad said. “She’ll miss ranch life. She’s got horse blood in her veins.”

After breakfast, I brought Patches into the barn. Dad followed me, and as I saddled up, he started deluging me with all sorts of advice, telling me to hope for the best but plan for the worst, neither a borrower nor a lender be, keep your head up and your nose clean and your powder dry, and if you do have to shoot, shoot straight and be damn sure you shoot first. He wouldn’t shut up.

“I’ll be fine, Dad,” I said. “And you will, too.”

“’Course I will.”

I swung up into the saddle and headed over toward the house. The sky was turning from gray to blue, the air already warming. It looked to be a dusty scorcher of a day.

Everyone except Mom was standing on the front porch, but I could see her watching me through the blur of the bedroom window. I waved at them all and turned Patches down the lane.

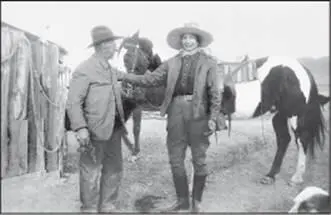

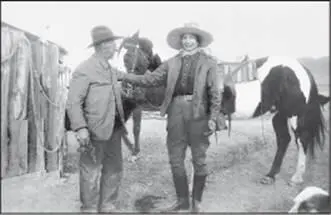

Lily Casey with Patches

THE DIRT ROAD RUNNINGwest from Tinnie was an old Indian trail packed down and widened over the years by wagon wheels and horse hooves. It followed the Rio Hondo through the foothills of the Capitan Mountains north of the Mescalero Apache reservation. The land in those parts of southern New Mexico was easy on the eyes. Cedars grew thick. From time to time I saw antelope standing at the riverbank or bounding down a hillside, and occasionally, a few skinny range cattle wandered by. Once or twice a day Patches and I passed a lone cowboy on a gaunt horse, or a wagonful of Mexicans. I always nodded and said a few words, but I kept my distance.

Late each morning when the sun got high, I looked for a shady spot near the river where Patches could graze on the short grass. I needed rest, too, to keep my wits about me. A walking horse could be as dangerous as a galloping one, since the easy rhythm could lull you into drowsing off just as a rattler darted into your path and your mount spooked.

When it started to cool, we moved on again and kept going until it got dark. I’d make a sagebrush fire, eat some jerky and biscuits, and lie in my blanket, listening to the howling of the distant coyotes while Patches grazed nearby.

Читать дальше