For those two weeks we fell into a routine: I stopped in to see Janet before work-usually with a raspberry muffin from a place she liked, though she had very little appetite-and spent three or four hours there at night. I brought her newspapers and political magazines. Her mother, who believed in the healing powers of red meat, brought meatball and roast beef sandwiches that Janet took one look at and set aside. If she could talk we talked about everything around the edges of us-the weather, the world, the strenuous craziness of the early Christmas season. Gerard visited a few times and made her laugh with his Bob Dylan imitations (for which he was locally famous), singing “Train of Love” so loud at one point that the nurses came in to ask him to cool it. We were at the tail end of Jacqueline’s addition-hanging interior doors, grouting bathroom tile-and she was pleased, and we had our priorities straight, and so, on those early December days, we didn’t worry about cutting ourselves a little slack.

Janet was still eleventh on the transplant list, and no one was talking about her leaving the hospital anymore. But for those short, cold days we all pretended things could go on like that indefinitely. It was a kind of trick, a wishful self-hypnosis, and I suppose we all knew it-Janet’s mother, me, the orderlies and good nurses who emptied her bedpans and rubbed her back and changed her IV-but we needed a stretch of relative peace then, and for fourteen or fifteen days we had it.

And then, on the second Sunday of the month, the trick stopped working. That day I took my mother out for a nice Yankee pot roast lunch and an ice cream sundae and spent a little time watching TV with her in the community room at Apple Meadow. I hoped she would remember the Thanksgiving dinner at Amelia’s house-the first good hour at least-but it seemed to have left no mark on her memory. Janet had skidded off her radar screen. She went on and on about Lauren, a sometime friend who lived down the hall and who, my mother seemed to think, was constantly chasing the men residents who were rumored to be still capable of having sex. “Your father and I enjoy it as much as the next person,” she told me, in a voice right out of the high school hallways. “Probably more than the next person, if you want to know. But we are discreet about it, Ellory. Why, just last week we were in Aruba, and you children were asleep in your rooms and they have these beaches there, you know, not far from the hotel, and we sneaked out on the beach and he started to-”

“Mum, you don’t want to keep watching football, do you?” I said.

And so on.

When I got back to my apartment the light on the phone machine was blinking, and Janet’s mother’s voice was on the tape. “Jake, Jake, Jake. Come right away when you get this. Come right away.”

Janet was all bones and sallow skin, eyelids slowly fluttering, incommunicado. Her left lung was working like an old, worn-down bellows that had been mostly filled up with sand, and her right lung was not working at all.

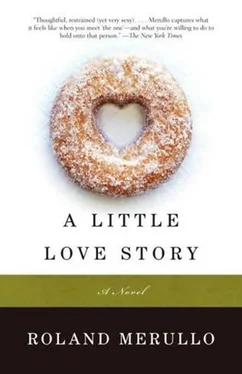

I sat there with her and her mother for several hours, watching her, touching her, sinking inch by inch in a cold quicksand. Amelia was making the rosary beads go through her fingers faster and faster, and would not eat, and would not leave the room. I stayed until ten o’clock, then left the hospital and just drove aimlessly back and forth on the long east-west avenues of the Back Bay: Beacon to Marlborough to Boylston to Commonwealth, just staring out at the holiday lights, just shifting gears, just going from brake to gas to brake and slamming in the clutch. Snow was falling, large indifferent flakes twirling and skidding through the headlight beams. Eventually, I turned west onto Commonwealth and kept going as if headed home, and then, because I was near Betty’s, I stopped and bought two coffees and half a dozen doughnuts-Carmine wasn’t there-and took them over to Gerard’s.

Gerard rented the top floor of a maroon and gold Victorian in North Cambridge, not far from where Anastasia and the girls lived. Two small bedrooms, a room for his books, computer, and bicycles, a kitchen and bath-the place suited him well enough, though the ceilings slanted down in a way that made for a lot of bruised foreheads. “It has encouraged me to begin dating short women,” he liked to joke.

I told him about the change in Janet’s condition. We drank the coffee and went through all the doughnuts-unusual for him-and then we sat at his fifties-style Formica-topped table, which was the one piece of furniture Anastasia had let him take from the house, and looked out different windows. I called my apartment four times and the hospital twice. I did not want to go home. At last I said, “Let me look at the computer, will you?”

I brought up the search engine and plugged in the same thing I always plugged in: cystic fibrosis and lung transplants . The same 239 pages came up. I started to flip down through them, looking for something new, but Gerard was standing at my shoulder. “Try something else, will you?” he said impatiently. “That’s not the way to do research.”

“Something else like what?”

“I don’t know. Anything. Last ditch or something. Don’t just hit the same stupid nail in over and over again. Refine the search. What’s wrong with you?”

I typed in cystic fibrosis, transplants, last ditch , without much hope, and got forty-seven pages. I’d seen most of them before: stories of fifteen-year-olds whose lives had been saved, or prolonged, by a cadaveric transplant; professional papers so filled with medical terminology that you needed a translator to understand one-tenth of them; statistics on survival rates with various bacteria, in various hospitals, in various countries. I tapped the down arrow without much enthusiasm. When I hit the eleventh page I saw Living Lobar Transplantation in Cystic Fibrosis Patients , and I stopped there. I almost moved on, but something was making me keep looking at those words, and then a little faint bell sounded, a little blink of light.

“What?” Gerard leaned down closer.

I opened the page and we read it.

What it said was that, for cystic fibrosis patients, a lung transplant was the treatment of last resort. I knew that already. It went on to say that the number of people who wanted new lungs far exceeded the number of lungs available at any given time. I knew that, too. But in the next paragraph there was something about a surgeon in California who had been the first to try what was called a “living lobar transplant,” in 1993, removing a lobe each from two healthy donors and sewing them into a patient whose lungs had been destroyed by the same bacteria Janet had. The patient had lived three years. The operation was riskier and more complicated and more expensive than the usual cadaveric transplant, and so it was done only about a dozen times a year in America, but some recipients were still alive and doing well seven years after they’d received the new lobes.

There were six or eight more paragraphs, having to do with complications and problems, but I did not want to know about that then. “My mother mentioned this,” I told Gerard.

“Your mother mentions it,” he said over my shoulder, in the tone of voice he reserved for the courts and the IRS and the big multilingual corporations. “She’s got sixty-three brain cells left, she mentions it. Nobody else says a word.”

Before he was finished with that sentence, I was offline and on the phone to the hospital, asking for Doctor Ouajiballah. But it was one o’clock in the morning. Doctor Ouajiballah, the nurse on duty told me, would not start rounds again until eight.

When I hung up, Gerard said, “I’ll doan.”

“What?”

“I’ll doan. You need a donor, I’ll doan. I’ll give her one of my lobes.”

Читать дальше