At home, I showered, made myself a supper of black beans, brown rice, red wine, and a Fudgsicle, and went into my studio to paint.

“Studio” is probably too fancy a word. I had a three-room, 1,300-square-foot apartment in an old factory building where people had at one time made shoes. There was a small kitchen, a bedroom almost completely filled by the bed and bureau, a bathroom with old-fashioned, six-sided white tiles on the floor, and a very large awkward room with four tall, thirty-two-paned factory windows-my studio. I had two easels set up there, racks for old paintings, and shelves with tubes of paint, cans of gesso, pencils and charcoal and pastel chalks, sketches, brushes, drop cloths to protect a floor that had been gouged and grooved by vibrating shoe machines a hundred years before, then more or less refinished.

In those days I was painting with oil on linen, and I liked to size the linen canvas myself with rabbit-skin glue, and then make a mix of titanium white gesso and a marble-dust filler and apply it in even strokes, all in one direction for the first layer, and then in the cross direction for the second. I liked to make the canvas frames by hand, cutting four pieces of poplar with my miter saw and joining them with mortise and tenon and pin. I painted fairly realistic portraits, of women mostly, but also of children and men. The people were sometimes purely imagined and sometimes based on actual people who had made some mark on my life, and often I stayed up very late working on them. Every eighteen months or so I had a gallery show and sold a few canvases for roughly what I would make in two weeks of carpentry.

I finished-or reached a stopping point-at eleven-thirty, cleaned up, and was in bed by midnight, when the phone rang.

I thought it was Gerard. In those days he often called me late at night to see how things had gone in the nonworking part of my day and to ask what supplies we might need from the lumberyard to start work the next morning. Another person would have waited until the next morning to talk about how things had gone, and asked about supplies in the afternoon when we were finished for the day. But Gerard could not be held to the standards of another person. He brought Virginia Woolf to work for lunch-hour reading. He liked to recite Latin poetry, by heart, sometimes shouting Lente , lente currite, noctis equi! out over the streets of Cambridge, Allston, or Beacon Hill from a three-story staging. He was addicted to doing research on his computer, and he’d talk for hours about supernovas and scuba equipment, the political situation in Kazakhstan, Tour de France champions, diseases of the beech tree, NASCAR standings. His interests were encyclopedic, his memory photographic, his sense of loyalty and need for affection without bounds. As a boy, his family life had been less than perfectly nurturing. As a young man, he’d dropped out of college-where we’d been friends-and then spent time in a hospital for bipolar problems. I had let him live at my place for a while between college and marriage. And later, I’d hired him to work with me, building additions, fire escapes, three-car garages, tearing out whole sections of houses that had gone rotten or been eaten away, and replacing them with plumb walls and level floors and neat interior woodwork. During the previous year-the Evil Year, I called it-he had paid me back with interest for whatever favors I’d done. So we had complex worlds swirling around in the alleys and avenues of our friendship-gratitude, shame, grief, old childhood wounds, new arguments, a speckled canvas of deep affection that we never talked about.

But it wasn’t Gerard’s voice in any case. The person on the line had the mother of all colds.

“It’s Janet,” she said. “Rossi.” She turned her mouth away from the phone to cough. “I’m sorry if I was rude today. It’s hard for me to talk at work.”

“You weren’t too rude.”

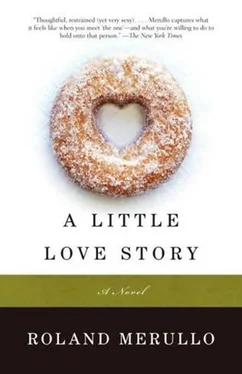

“I hope this isn’t too late to call. You were up this late at the doughnut shop, so I guessed you were a night person.”

“A night person and a day person,” I said. She coughed again and I was going to make a little remark about it, but my sense of humor can get strange sometimes when I’m nervous-I’ve been told that more than once-so I held back. “Where do you work?” I asked her. What I kept myself from saying was, “In which mine?”

“The governor’s office.”

“I saw him on the TV at O’Casey’s last week.”

“He’s running again, so things are a little hectic.”

He should run , I almost said, because I had some kind of instinctive, bone-and-blood dislike for the man, even though he’d been a decent governor up to that point. He should start running at the door of the State House and not stop until he gets to Ixtapa , I had an urge to say. But I was holding on to my comic side with both arms by then.

She said, “I called to see if the dinner invitation is still good.”

“Let me check the calendar.” I picked up my August National Geographic and made the pages flap. “I have a Friday in 2006,” I said. “November.”

“You’re paying me back.”

“Or this coming Friday night. Nothing between, I’m sorry to say… except this Saturday night. Also good.”

There was a long pause then. It wasn’t health-related.

“I can be a little goofy this late,” I said.

“Are you on something?”

“Paint fumes.”

“Oh.”

“That was a joke. There’s a new Vietnamese restaurant on Newbury Street. Diem Bo. It’s a great place if you like that food. Noodles and so on. Shrimp. That coffee they make with all the milk and sugar in it.”

“I love Vietnamese coffee.”

“Good. Seven o’clock okay?”

“Perfect.”

“Friday’s better, it’s sooner than Saturday. Friday okay? Meet you at Diem Bo?”

“Fine.”

“Good. It made me happy that you called.”

“I’ll see you Friday.”

We hung up and I lay awake for a long time, thinking I shouldn’t have said it made me happy that she’d called, then thinking it was alright. Thinking I wasn’t really ready to go on a date just yet, and then thinking I might be.

ON FRIDAY AFTERNOONS Gerard and I quit for the day at four o’clock and went to O’Casey’s for a drink. In addition to his other passions and talents, Gerard was a world-class bicyclist, and very careful about what he put into his body, so he usually had tomato juice with a twist of lime. I like beer but beer does not like me, so I usually had a glass of Merlot. Bub, the bartender, made no secret of the fact that he thought our choice of beverages unmanly. He called us “Red One” and “Red Two,” though Gerard is dark-haired, going bald, and my hair is the color of old hay.

“Good that you’re dating again,” Gerard said, when I told him about my plans for that evening. “I’ve been worried about your mental health… which is a subject I know something about.”

“Everything is a subject you know something about.”

I asked Bub for some Beer Nuts to go with the Merlot. He smirked.

“And Vietnamese is the right choice,” Gerard went on. “It’s sex food.”

“How do you figure?”

“Just is.”

“What’s love food?”

“Greek, naturally.”

I nodded. Gerard’s last name was Telesrokis. “What’s marriage food?”

“French. Or a steak house.”

“What’s Thai food, then?”

“Sex food, too. Kinky, though.”

“Chinese.”

“Chinese is old-fashioned courtship. Szechwan especially.”

“Alright.”

“Vietnamese is an excellent first date. In time, if things go well, you can progress to Greek or Thai, depending.”

“On?”

Читать дальше