“I came through the door ordinary. Then I went to wild gorilla.”

She didn’t smile.

“He deserved it,” I said. “I’m only seventy-five percent sorry.”

“I’m not asking you to be sorry. I’m the one who’s sorry… that I ever let him touch me. You can’t imagine the depth and range of my sorrow right now.”

“Why did you?”

She shrugged.

“Why did you let him touch you?” I said again, but I was just talking, filling up air. I was feeling less sorry by the second. By the time Janet spoke again I was down to thirty-five percent.

“Sometimes you just want a little pleasure, that’s all. Some connection with somebody. Some, I don’t know-”

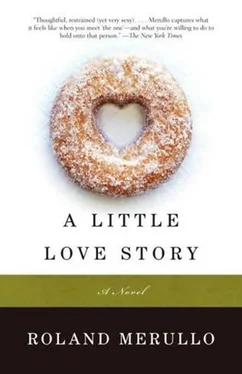

“A doughnut.”

“What?”

“A doughnut, you want a doughnut. You want your share of sweetness to make up for all the shit you have to go through. You deserve the two doughnuts, or the kiss, or the cocaine, or the new car, or the new earrings, or the new fishing rod.”

“What in the name of God are you talking about, Jake? What fishing rod? I don’t-”

“Now you’re going to lose your job,” I said, to reel myself in.

She laughed then, a small laugh with a hem of bitterness along its edges. “Not before the election anyway. You heard him. ‘I fell! It’s nothing! Everyone out!’ When he goes to buy underwear he worries which brand will get him more votes. He’s the epitome of the political animal.”

“Why’d you sleep with him, then?”

It had slipped out, and I couldn’t pretend to myself anymore that I was just filling air. Janet looked at me, then looked forward again. An oily silence floated between us in the cab of the truck. Until that minute I’d done an excellent job of not being jealous. From the time I’d read the note she left on my sink, jealousy had been whispering in my ear night and day. I’d see the governor on TV and I’d look at his hands and wonder where and how those hands had touched her. I’d look at his mouth. I’d hear a radio talk show host-this was rare-say he was handsome, or dignified, or that his plan to execute criminals meant he was the first governor we’d had in years with any cojones; I’d wonder if she’d ever touched his cojones; I’d notice that Boston magazine had named him one of the city’s top ten eligible bachelors. I’d see news clips of the governor with his daughters, or on his morning run, or lining up to donate blood for the hundred and twenty-seventh time with a big sappy smile on his face. And so on. It’s one thing for your lover to have had lovers before-who doesn’t have to deal with that, high-school sophomores? It’s something else to have that other person’s face and voice and picture and name ricocheting around every bar you step into, every newsstand you walk past, every radio station you listen to on your way to work. Jealousy fun house mirrors.

Still, in the months before I met Janet, I’d had a lot of practice turning my mind away from certain types of thoughts, and, in the time I’d known her, whenever jealousy made one of its runs, I’d just stepped aside and let it crash past. Who knows why my little sidestep move wasn’t working that night? Because I’d actually wrestled around on the floor with the governor, maybe? Because he was still reaching into a part of my life with his pathetic I-love-yous long after he should have bowed gracefully out? Because the part of my life with Janet in it was becoming more important to me every day? Who knows?

The traffic softened up slightly. We headed west at a slow pace.

After a while Janet said, “I don’t ask you things like that.”

“I know it.”

“I don’t ask you who you’ve been with or anything about Giselle, or why you didn’t date for a year after you broke up with her, or even if you’re sleeping with someone else now.”

“I’m not.”

“Good. I’m not either.”

A mile or so of edgy silence, not so bad now. This was the weird complicated tango of modern relationshipping. This was as ancient as dust and sweat.

She said, “I was lonely. I got just very lonely. Of the four other men I work with, one is gay, two are married, and the other one has egg on his face when he comes to work.”

“Literal egg?”

She didn’t laugh. “I’m not exactly… I don’t exactly have attractive guys lined up at my door, no offense.”

“You’re beautiful, you’re smart, you’re sexy. What are you talking about?”

I could feel her looking at me across the cab of the truck, but I was afraid to look back.

She said, “Come on, Jake. I cough. I spit. I ply myself with pills before every meal when I’m out on dates in restaurants. I’m a fun time, but not exactly what you’d call a good long-term investment.”

“Not if I can help it,” I said, without thinking.

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning I’m going to keep you alive.”

“By the force of your heroic masculine will?”

“Don’t insult the force of my heroic masculine will,” I said. “I have a perfectly solidly average-sized heroic masculine will, maybe slightly larger.”

She didn’t laugh then, either, but I glanced across the seat and caught something in her eyes, one flash of good light. We drove along. “Where are you taking me?”

“Sanctum sanctorum,” I said. It was Gerard’s term for a woman’s body. It had just slipped out-like everything else I had been saying on that blessed night.

“You are an odd soul, Joe Date.”

“To New York or by bus,” I said. One of my mother’s jokes.

“You are essentially odd. If you ran for office, you’d never make it past the primary.”

“Thank you. I consider that a high compliment. But could we keep all references to running for office out of the conversation? All jerkoffs?”

“Okay.”

“I have the blood of jerkoffs on my hands.”

“You’re going goofy on me,” she said.

“I’m on a crime spree. I’ve assaulted an elected public official and now I’m going to trespass on monastery grounds.”

“He won’t press charges,” Janet said. “What monastery?”

“We’re going to see my brother. The monk. Then we’re going to New York or by bus.”

MY BROTHER ELLORY is eight years and two months older than I am. After a brilliant teenage career of rebelling against what he called “our upper-middle-class subterranean upbringing”-including one glorious night in which he drove my father’s new Mercedes convertible off the road, between two pine trees and down the third fairway at the Wannakin River Golf Club-he decided to really hit my parents where they lived, and he’d converted to Catholicism. In the beginning, this conversion had everything to do with a college girlfriend named Renée St. Cyr (who believed that premarital intercourse was approved of by the Good Lord, in her particular case, as long as the other intercoursee was also Catholic), but soon it took on a life of its own.

My brother started to attend mass at the radical church near the State House that let homeless people sleep between its pews. He started to talk about “the Lord” all the time. He stopped driving cars onto golf courses. A year into this our father died, and my brother felt so guilty that he decided to leave his old life behind entirely and become a monk. After a decade or more of monkhood, he’d persuaded the abbot to let him live as a hermit in a one-room cottage on the monastery grounds (he told me there was some precedent for this in Church history), and he spent his days there praying and chopping wood, growing vegetables to give away to the local food pantry, and, three or four times a week, walking up to the main monastery buildings to teach and counsel novices. After the initial shock, my mother was not really unhappy about all this. If nothing else, it meant that Ellory would never again get his name in the paper under POLICE BLOTTER, and embarrass her at the hospital. It didn’t matter very much to me one way or the other, except that I saw him less. He was still my brother. He still smoked, still gave the abbot some trouble the way he’d given his parents trouble, and his teachers, his scoutmaster, his golf coach, and so on.

Читать дальше