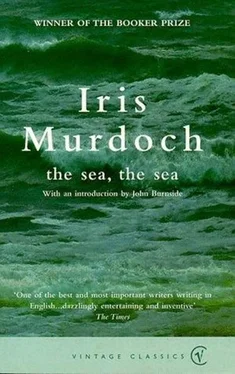

Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sea, the Sea

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sea, the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sea, the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Charles Arrowby, leading light of England's theatrical set, retires from glittering London to an isolated home by the sea. He plans to write a memoir about his great love affair with Clement Makin, his mentor, both professionally and personally, and amuse himself with Lizzie, an actress he has strung along for many years. None of his plans work out, and his memoir evolves into a riveting chronicle of the strange events and unexpected visitors-some real, some spectral-that disrupt his world and shake his oversized ego to its very core.

The Sea, the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sea, the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Can’t she get a job or-’

‘ Fob? Pam? Laissez-moi rire! Pam was never an actress, she was a starlet. She can’t do anything. She’s lived on men all her life. She lived on Ginger and she lived on some other poor American fish before that and God knows who before that. Ginger still pays her fantastic sums in alimony. And of course she’ll only consent to leave me if I agree to do the same. And do you know, I’m still paying alimony to Rosina, though she’s earning five times what I am. Suis-je un homme, ou une omelette? Sometimes I wonder. I was so bloody fed up and anxious to get rid of her I signed everything. God, if you would only remove Pamela too! You’re a lucky dog. Good clean fun every time and then you ditch them. Christ, you even got away from Clement. Why did I never learn?’

‘If you think I had a joy-ride with Clement-’

‘The trouble with you, Charles, is that basically you despise women, whereas I, in spite of some appearances to the contrary, do not.’

‘I don’t despise women. I was in love with all Shakespeare’s heroines before I was twelve.’

‘But they don’t exist, dear man, that’s the point. They live in the never-never land of art, all tricked out in Shakespeare’s wit and wisdom, and mock us from there, filling us with false hopes and empty dreams. The real thing is spite and lies and arguments about money.’

It might seem from this account that Perry was doing all the talking, and indeed by the end of the evening he was. He is endowed with an Irish flow of words, and when thoroughly drunk is difficult to interrupt. I was in any case in a mood to incite him rather than to talk myself. I was soothed by his eloquent lamentations and I must confess rather cheered up by his troubles. I am afraid that I was pleased rather than otherwise that his second marriage had failed; I should have felt a certain chagrin had I been the involuntary cause of his being happy en deuxième noces. Such feelings do me no credit; but they are not uncommon ones.

We were sitting in the rather large and handsome dining room of Peregrine’s flat. A white tablecloth, much stained with wine, covered the table and looked as if it had been there for some time. Perry had moved his divan bed into this room, and had even installed an electric kettle and an electric cooking ring (on which I had cooked the curry) so as to be able to leave the rest of the flat to Pamela. The ring stood on a square of newspaper which was covered with food droppings. The charwoman had left after being insulted by Pam. The room was very dusty and smelt of burnt saucepans and dirty linen. However, as Perry said, the door could be closed and locked.

Peregrine Arbelow has, as I think I said earlier, just about the largest face that I have ever seen on a human being; though when he was young, in his ‘playboy’ days, this did not prevent him from looking handsome. He has a large round face, now rather fat and flabby, framed (with the help of science) by short thick chestnut brown curls. (It was he who advised me about the rescue operation on my own hair.) His large eyes have retained a look of innocence or perhaps simply puzzlement. He is a big stout man, always dressed, even in hot weather, in tweedy suits with waist-coats. He has a watch and chain. He speaks with a light touch of the accent of his native Ulster, which of course disappears absolutely on the stage, unlike Gilbert Opian’s lisp. He is an excellent comic, though not as good as Wilfred, but then nobody is.

I thought it was time to get off the dangerous topic of women. ‘Been to Ireland lately?’ This always set Perry off and was a guaranteed subject-changer.

‘Ireland! There’s another bitch. Christ, the Irish are stupid! As Pushkin said about the Poles, their history is and ought to be a disaster. At least the Poles suffer tragically, the Jews suffer intelligently, even wittily, the Irish suffer stupidly, like a bawling cow in a bog. I can’t think how the English tolerate that island, there ought to have been a final solution years ago, well they did try. Cromwell, where are you now when we really need you? Belfast has been kicked to pieces. Nobody cares. The pain of it, Charles, the pain of it, the bloody suffering, the degradation, the bloody tit for tat. Why can’t they let the thing stop somewhere, like Christ did? Could a hundred saints save that island, could a thousand? And I can’t just forget it, it’s like the shirt of what’s his name, it’s on me, it’s crawling on my flesh. The only thing I get out of it is sometimes, in some moods. I can actually feel pleased that other people are worse off than me, that their beloved husband or son or wife has been shot down before their eyes, or that they’ve got to sit in a wheelchair for the rest of their life. That’s how vile I am! I live Ireland, I breathe Ireland, and Christ how I loathe it, I wish I were a bloody Scot, that’s how bloody awful it is being Irish! I think I hate Ireland more than I hate the theatre, and that’s saying something!’

At that moment the door opened and Pamela put her head round it. Then, swinging on the door, she half stepped half fell into the room and gazed at us glassily. She was wearing a coat and had evidently just come in. She was still handsome, with a lot of tumbling wavy grey hair, now rather bedraggled. Her smudged scarlet mouth turned down at the corners in an aggressive unhappy sneer. She stared at me, screwing up her eyes, ignoring Perry. I said, ‘Hello, Pam.’

She turned round laboriously, still holding on to the door, and started to go out, then turned about, with her face wrinkled up in a pout and her lips working, and having assembled enough saliva in her mouth, spat onto the floor, leaned forward to inspect the spit, and reeled away leaving the door open.

Peregrine leapt to his feet, rushed to kick the door violently shut, then picked up his glass and hurled it into the fireplace. It failed to break. He ran round the table literally foaming at the mouth, lifted it high with a cry of ‘Aaaagh!’ , a sound like a spitting cat only with the volume of a lion. I rose and took the glass out of his hand and put it on the table. He then walked slowly towards the door, looked at the place where Pamela had spat, tore a piece off one of the filthy newspapers and carefully laid it over the spittle. Then he returned to his seat. ‘Drink up, Charles, dear chap. You aren’t drinking. You’re sober. Drink up.’

‘You were saying about the theatre.’

‘You were so right not to publish your plays, they were nothing, nothing, froth, but at least they didn’t pretend to be anything else. Now you’re offended, vanity, vanity. Yes, I hate the theatre.’ Perry meant the London West End theatre. ‘Lies, lies, almost all art is lies. Hell itself it turns to favour and to prettiness. Muck. Real suffering is-is-Christ, I’m drunk-it’s so-different. Oh Charles, if you could see my native city-And that spitting bitch-How can human beings live like that, how can they do it to each other? If we could only keep our mouths shut. Drama, tragedy, belong to the stage, not to life, that’s the trouble. It’s the soul that’s missing. All art disfigures life, misrepresents it, theatre most of all because it seems so like, you see real walking and talking people. God! How is it when you turn on the radio you can always tell if it’s an actor talking? It’s the vulgarity, the vulgarity, the theatre is the temple of vulgarity. It’s a living proof that we don’t want to talk about serious things and probably can’t. Everything, everything, the saddest, the most sacred, even the funniest, is turned into a vulgar trick. You’re quite right, Charles, I remember your saying about old Shakespeare that he was the-he was the-only one. Him and some Greek chap no one can understand anyway. The rest is a foul stinking sea of complacent vulgarity. Wilfred felt that. Sometimes I remember he looked so sad, after he’d had them laughing themselves sick. Oh Charles, if only there was a God, but there isn’t, there isn’t, at all-’ Perry’s big round brown eyes were filling with tears. He fumbled for a handkerchief, then used the tablecloth. After a moment he added, ‘I wish I’d stayed at Queen’s and become a doctor. As it is I crawl on everyday towards the tomb. When I wake in the morning I think first of death, do you?’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sea, the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.