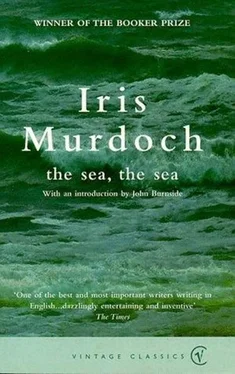

Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sea, the Sea

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sea, the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sea, the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Charles Arrowby, leading light of England's theatrical set, retires from glittering London to an isolated home by the sea. He plans to write a memoir about his great love affair with Clement Makin, his mentor, both professionally and personally, and amuse himself with Lizzie, an actress he has strung along for many years. None of his plans work out, and his memoir evolves into a riveting chronicle of the strange events and unexpected visitors-some real, some spectral-that disrupt his world and shake his oversized ego to its very core.

The Sea, the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sea, the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

None of this stopped me from rather worshipping Uncle Abel and dancing around him like a pleased dog. At least I did so when I was a young child. Later, because of James, I was slightly more dignified and aloof. Was my father sometimes hurt because I found Uncle Abel so picturesque? Perhaps. This thought saddens me now as I write with a special piercing sadness. He did not care about the worldly goods, but, though he never showed it, he might have felt sorry, again for my sake, that he was so much less of a ‘figure’. My mother may have intuited some such regret in him (or perhaps to her he expressed it) and this may have contributed to the irritability which she could not always suppress when the Abel Arrowbys were mentioned, or especially when they had lately been with us on a visit. They did not in fact visit us very often, since my mother felt that we could not ‘entertain’ them in sufficient style, and would embarrass them, when they did come, with aggressive apologies concerning our humbler way of life. We, I should add, lived upon a housing estate where loneliness was combined with lack of privacy. My visits to stone-built tree-surrounded Ramsdens were usually made alone, because of my mother’s horror of being under her brother-in-law’s roof, and my father’s horror of being under any roof except his own.

I must now, in mentioning my mother, speak of Aunt Estelle. She was, as I have said, an American, though where exactly she hailed from I do not remember to have discovered; America was a big vague concept to me then. Nor do I know where or how my uncle met her. She certainly represented to me some general idea of America: freedom, gaiety, noise. Where Aunt Estelle was there was laughter, jazz music, and (how shocking) alcohol. This again might give the wrong impression. I am speaking of a child’s dream. Aunt Estelle was no ‘drinker’ and her ‘wildness’ was the merest good spirits: health, youth, beauty, money. She had the instinctive generosity of the thoroughly lucky person. She was, in a vague way, demonstratively affectionate to me when I was a child. My undemonstrative mother watched these perhaps meaningless effusions coldly, but they moved me. Aunt Estelle had a pretty little singing voice and used to chant the songs of the first war and the latest romantic song-hits. ( Roses of Picardy, Tiptoe through the Tulips, Oh So Blue, Me and Jane in a Plane, and other classics of that sort.) I remember once when she came one night at Ramsdens to ‘settle me down’, her singing a song to the effect that there ain’t no sense sitting on the fence all by yourself in the moonlight. I found this very droll and made the mistake of trying to amuse my parents by repeating it. ( It ain’t no fun sitting ’neath the trees, giving yourself a hug and giving yourself a squeeze. ) It is probably in some way because of Aunt Estelle that the human voice singing has always upset me with a deep and almost frightening emotion. There is something strange and awful about the distorted open mouths of singers, especially women, the wet white teeth, the moist red interior. Altogether my aunt was for me a symbolic figure, a modern figure, even a futuristic figure, a sort of prophetic lure into my own future. She lived in a land which I was determined to find and to conquer for myself. And in a way I did, but by the time I was king there she was already dead; and it seems strange to think that we never really knew each other, never really talked to each other at all. How easily, later on, we could have bridged the years and how much we would have enjoyed each other’s company. I mentioned her occasionally to Clement who said she was the only one of my relations she would have liked to meet. (My parents of course never met Clement, since it would have made them very unhappy to know that I was living openly with a woman twice my age; but I could have introduced her to my aunt.) When Aunt Estelle was killed in a motor accident when I was sixteen I was less upset than I expected. I had other troubles by then. But it is sad to think that, although she was so kind to me in her absent-minded way, she probably never thought of me except as James’s awkward boorish undistinguished little cousin. She was a marvel to me, a portent. Sorting out oddments at Shruff End two days ago I came across a photograph of her. I could not find one of my mother.

My mother did not exactly dislike Aunt Estelle, nor violently disapprove of her, though she shuddered at the noise and the drink; and she was not exactly envious because she did not want the worldly things that pleased Aunt Estelle. She was just thoroughly depressed by her existence and cast into the gloom and irritation which I mentioned earlier by her visits. It may be that my uncle and aunt thought that my upbringing was too strict. Outsiders who see rules and not the love that runs through them are often too ready to label other people as ‘prisoners’. It is conceivable that clever Uncle Abel and liberated Aunt Estelle actually pitied my father and myself, and blamed my mother for what they regarded as a repressive regime. If my mother suspected the existence of such judgments she must have felt pain and resentment; and this resentment may even have had the effect of making her still stricter with us. It is also possible that, divining my childish fantasies concerning that ‘America’ which Aunt Estelle represented to me, she felt jealous. Much later I wondered if she imagined that my father was attracted by his vivacious sister-in-law. In fact I am sure that he had no deep feelings of any sort about Aunt Estelle, except again in relation to me, and that my mother must have known this. (How egoistic I sound as I describe myself as the centre of my parents’ world. But I was the centre of their world.) In the end I ceased looking forward to Aunt Estelle’s visits, although they always excited me when they happened, because they made my mother so depressed and cross. Our house was always somehow spoilt by these visits, and took a little time to recover. As the Abel Arrowby Rolls-Royce was finally waved away down the street, my mother would fall silent, answer in monosyllables, while my father and I tiptoed about, avoiding each other’s eyes.

I was happy at school, but there were no close friendships, no dramas there, no dearly beloved schoolmasters, though some influential ones, such as Mr McDowell. My aunt and uncle loomed as large significant romantic figures, focuses of obscure emotion, in a childhood which was in a way curiously empty. Yet also they were remote, a little hazy, a little cloudy, partly of course because they were only marginally interested in me. I never felt that they really saw me or even looked at me much. With cousin James it was far otherwise. Silently, James and I, from earliest moments, were acutely, suspiciously, constantly aware of each other. We watched each other; and by a mute instinct kept this close mutual attention largely secret from our parents. I cannot say that we feared each other; the fear was all mine, and was a fear not exactly of James but of something that James stood for. (This something was I suppose my prophetic veiled conception of my own life as a failure, as a total disaster.) But we lived, in relation to each other, in a cloud of discomfort and anxiety. All this of course in silence. We never spoke of this strange tension between us; perhaps we would not have been able to find words for it. And I doubt if our parents had any idea of it. Even my father, who knew that I envied James, had no conception of this.

As I have indicated, part of my unease about my cousin consisted in a fear that he would succeed in life and I would fail. That, on top of the ponies, would have been too much. It is scarcely possible to say how far my ‘will to power’ was inspired by a deep original intent to outshine James and to impress him. I do not think that James felt any special desire to impress me, or perhaps he knew that he did not have to try. He had all the advantages. He received, and this is where I really began to grind my teeth, a better education than I did. I went to the local grammar school (a dull decent school, now defunct), James went to Winchester. (Perhaps this was a mixed blessing. In a way he never recovered. They say they rarely do.) I got myself a reasonably sound education, and especially I got Shakespeare. But James, it seemed to me then, was learning everything. He knew Latin and Greek and several modern languages, I had only a little French and less Latin. He knew about painting and regularly visited art galleries in Europe and America. He chatted familiarly of foreign places. He was good at mathematics, he won prizes for history. He wrote poetry which was published in the school magazine. He shone ; and although he was not at all boastful, I increasingly felt myself, and was made to feel, a provincial barbarian when I was with James. I felt a gap between us widen, and that gap, as I more intelligently surveyed it, began to fill me with despair. Clearly, my cousin was destined for success and I for failure. I wonder how much my father understood of all this?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sea, the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.