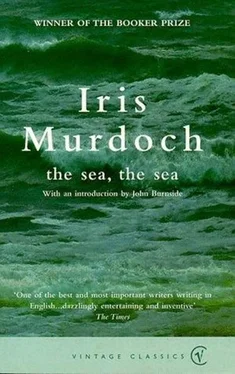

Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Iris Murdoch - The Sea, the Sea» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sea, the Sea

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sea, the Sea: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sea, the Sea»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Charles Arrowby, leading light of England's theatrical set, retires from glittering London to an isolated home by the sea. He plans to write a memoir about his great love affair with Clement Makin, his mentor, both professionally and personally, and amuse himself with Lizzie, an actress he has strung along for many years. None of his plans work out, and his memoir evolves into a riveting chronicle of the strange events and unexpected visitors-some real, some spectral-that disrupt his world and shake his oversized ego to its very core.

The Sea, the Sea — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sea, the Sea», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Searching for a place to plant my herb garden I have found some clumps of excellent young nettles on the other side of the road. I also managed to buy some fresh home-made scones in the village this morning. Some splendid local lady occasionally sells these through the shop. I am told she makes bread too, and I have ordered some. For lunch I ate rashers of cold sugared bacon and poached egg on nettles. (Cook the nettles like spinach. I usually make them into a sort of purée with lentils.) After that I feasted on the scones with butter and raspberry jam. I drank the local cider and tried to like it. The wine problem is still on the horizon.

I have found a few more letters in my dog kennel. They seem to arrive rather irregularly, and I have never yet seen the postman. No word from Lizzie. There is a missive from my cousin James which I shall record. It is characteristic.

My dear Charles,

I understand that you have purchased a house by the seaside. Does this mean that you have given up your theatrical activities? If so it must be a relief no longer to have to do hurried work with a ‘deadline’ in mind. I trust, in any case, that you are having a well-earned rest in your marine abode, that your ‘things’ have found satisfactory perches, and that you have a pleasant kitchen wherein to practise your brand of gastronomic mysticism! Have you retained your London flat? I confess I set you down as a dedicated Londoner, so this defection is surprising. I wonder if you have a sea view? The sea is always a refreshment to the spirit, it is good to see the horizon as a clean line. I could do with some ‘ozone’ myself. The weather in London is intolerably hot and the temperature seems to increase the traffic noise. Perhaps there is some physical cause for this connected with sound waves? I expect you are doing a lot of bathing. I always think of you as a fanatical swimming man. Pray let me hear from you in due course and if you are in town we might have a drink. I hope you are happily ‘settled in’ and on good terms with your house. I was interested in its curious name. With usual cordial wishes.

Yours,

James.

James’s letters to me contrive to be slightly patronizing, as if he were an elder brother, not a younger cousin; indeed they sometimes achieve that well-meaning almost parental stiffness which makes one’s own doings seem so puerile. At the same time, these letters, of which I regularly receive two or three a year, always seem to me to combine a dull formality with the faintest touch of madness.

Perhaps at this point I had better offer some longer and more frank account of my cousin. It is not that James has ever been much of an actor in my life, nor do I anticipate that he will ever now become one. We have steadily seen less of each other over the last twenty years, and lately, although he has been stationed in London, we have scarcely met at all. The reference in his letter to ‘having a drink’ is of course just an empty politesse. I have rarely introduced James to my friends (I always kept him well away from the girls), nor has he introduced me to his, if he has any. (I wonder how he heard about my ‘seaside house’? That too must be in the newspapers, alas. Is publicity to plague me even here?) No, cousin James has never been an important or active figure in the ordinary transactions of my life. His importance lies entirely in my mind.

We rarely meet, but when we do we tread upon a ground which is deep and old. We are both only children, the sons of brothers close in age (Uncle Abel was slightly younger than my father) who had no other siblings. Though we rarely reminisce, the fact remains that our childhood memories are a common stock which we share with no one else. There are those who, even if valued, remain sinister witnesses from the past. James is for me such a witness. It is not even clear whether we like each other. If I were told today that James was dead my first emotion might be pleasurable; though how much does this prove? Cousinage, dangereux voisinage had a quite special meaning in our case. I see I have used the past tense; and really, when I reflect, I see how much all this now belongs to the past: only the deeper parts of the mind have so little sense of time. As the years have rolled I have had less and less difficulty in resisting an image of James as a menacing figure. One day a friend (it was Wilfred), meeting him by accident, said, ‘What a disappointed man your cousin seems to be.’ A light broke, and I felt better at once.

When I was young I could never decide whether James was real and I was unreal, or vice versa. Somehow it was clear we could not both be real; one of us must inhabit the real world, the other one the world of shadows. James always had a sort of beastly invulnerability. Well, it goes right back to the start. As I have explained, I was early aware, through the sort of psychological osmosis of which children are so capable, that Uncle Abel had made a more ‘advantageous’ marriage than my father, and that in the mysterious pecking-order hierarchy of life the Abel Arrowbys ranked above the Adam Arrowbys. My mother was very conscious of this, and I am certain struggled in the depths of her religious soul ‘not to mind’. (She had a special way of emphasizing the word ‘heiress’ when she spoke of Aunt Estelle.) My father, I really believe, did not mind at all, except for my sake. I remember his once saying, in such an odd almost humble sort of voice, ‘I’m so sorry you can’t have a pony, like James…’ I loved my father so intensely at that moment and was at the same time conscious (I was ten, twelve?) that I could not express my love, and that perhaps he did not know of it, how much it was. Did he ever know?

As far as the material things of life were concerned the families certainly had different fates. James was the proud possessor of the above-mentioned pony, indeed of a series of such animals, and generally lived in what I thought of as a pony-owning style. And how I suffered from those bloody ponies! When I visited Ramsdens James sometimes offered me a ride, and Uncle Abel (also a horseman) wanted to take me out on a leading rein. Although passionately anxious to ride I always, out of pride and with a feigned indifference, refused; and to this day I have never sat on a horse. A perhaps more important, though not more burning, occasion of envy was continental travel. The Abel Arrowbys went abroad almost every school holiday. They drove all over Europe. (We of course had no car.) They went to America to stay with Aunt Estelle’s ‘folks’, about whom I was careful to know as little as possible. I did not leave England until I went to Paris with Clement after the war. It was not only their ponies and their wide-ranging motor cars that I envied here, it was their enterprise. Uncle Abel was an arranger, an adventurer, an inventor, even a hedonist. My dear good father was none of these things. My uncle and aunt never invited me to join them on those wonderful journeys. It only much later occurred to me, and the idea entered my mind like a dart (I daresay it is still sticking in there somewhere), that they did not ask me because James vetoed it!

As I said, the situation worried my father, I think, only on my behalf. It worried me on my behalf too, but also and quite separately on his. I resented, for him, his deprived status. I felt, for him, the chagrin which his generous and sweet nature did not feel for himself. And in doing this I was aware, even as a child, that I thereby showed myself to be his moral inferior. Although I had such a happy home and such loving parents, I could not help bitterly coveting things which at the same time, as I looked at my father, I despised. I could not help regarding Uncle Abel and Aunt Estelle as glamorous almost godlike beings in comparison with whom my own parents seemed insignificant and dull. I could not help seeing them, in that comparison, as failures. While at the same time I also knew that my father was a virtuous and unworldly man, whereas Uncle Abel, who was so stylish, was an ordinary average completely selfish person. I do not of course imply that my uncle was a ‘cad’ or a ‘bounder’, he certainly was not. He loved his beautiful wife and, as far as I know, was faithful to her. He was, as far as I know, an affectionate and responsible father. I am sure he was honest and conscientious in his work and in his finances, in fact a model citizen. But he was an ordinary self-centred go-getter, an ordinary sensualist. Whereas my father, although perhaps nobody ever knew this except my mother and me, was something quite else, something special.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sea, the Sea» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sea, the Sea» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.